Our photographer has visited the region surrounding Fukushima Daiichi. He updates us on the changes made.

Visitors travelling along National Route 6 today, which links Tokyo to Sendai in the Tohoku region (in the north east) and runs alongside the coast of Fukushima Prefecture, may not realise that they have just passed through the worst affected areas of the triple disaster of March 2011. Yet, National Route 6 bypasses the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant by fewer than 3 kilometres and passes through the towns of Okuma, Futaba, Namie as well as other areas still highly contaminated today, all of which can only be crossed by car and are officially, and euphemistically, referred to as “difficult-to-return” zones.

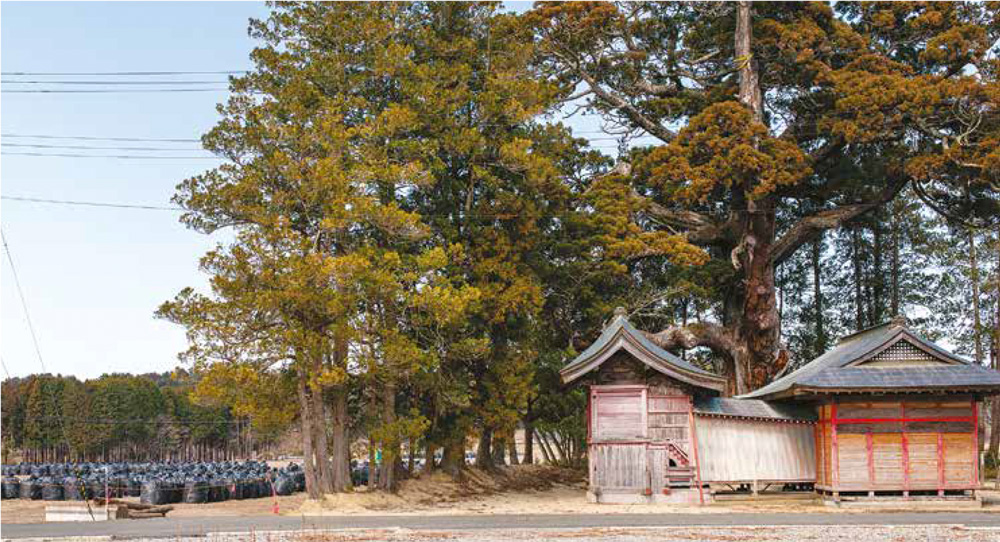

But, from the road, there remains little to be seen of the vast expanses of bulky black sacks full of contaminated waste and ghostly buildings left to rot. The eagle-eyed might spot the untended public spaces and abandoned farmland, though hardly more than in some other regions in Japan suffering from depopulation and the ongoing exodus from rural areas. Ten years after the catastrophic events, the state of the abandoned buildings continues to testify to the violence of the earthquake, the damage inflicted by the tsunami and the terror caused by the nuclear accident, which razed them to the ground one after another. It is the same in areas where the radiation level remains high and the return of residents is not an option.

Is there a desire on the part of the Japanese authorities to erase all traces of the disaster? The visit to the Futaba community provides an answer to this question and gives a good insight into the government’s ambition and the progress of its project.

In March 2011 all the inhabitants of Futaba, a small rural community where the nuclear power plant is located, were evacuated following the reactor’s meltdown. In 2020, 3% of the Futaba area was reopened to visitors, then the first permanent residents were allowed to return in February 2022. To achieve this, 25 new dwellings were built in the vicinity of a new railway station. In addition, and at great expense, a Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum was built as well as a centre for industry, new roads, offices for SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises), a hotel, souvenir shops, a luxurious town hall, and a gigantic concrete dam to protect the whole area in case of another tsunami.

In the decontaminated areas accessible to visitors, the very few buildings remaining from before the disaster that have not yet been razed to the ground, such as the fire station, are covered with murals as part of the “Futaba Art District”, another project to help revitalise the community. With Futaba as their foothold, the Japanese authorities intend to develop what they call “Hope Tourism” in the prefecture, which has been largely abandoned by tourists since the disaster.

The project is based on the fact that the Fukushima region is the only place on earth to have experienced a multiple disaster: earthquake, tsunami and nuclear catastrophe, and on the interest that the disaster can generate. The underlying message is that there are lessons to be learned from a region that has faced the awful tragedy of a nuclear accident, and that meeting those involved in the reconstruction efforts can be a source of reflection, inspiration and hope.

To this end, several three-day tours have been set up to visit different sites. Local accommodation is provided and there is the opportunity to pick strawberries grown in Soma or meet people involved in the reconstruction process, like a former employee of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), a fisherman or an inn owner. Meticulously organised, they highlight the government’s vision for nuclear safety and what it sees as the success of Fukushima’s reconstruction. Not surprisingly, opponents of nuclear power, critics of the government’s handling of the crisis and those who question the wisdom of the huge sums spent on decontamination and reconstruction of rural areas already in decline before the disaster have no say in the matter.

The promotion of this “Hope Tourism” is in fact the result of a project gradually developed over many years. A detailed website in both Japanese and English explains the project and lists the places that can be visited and the people you can meet (www.hopetourism.jp/en/).

Will all this investment in the reconstruction and promotion of tourism in Fukushima be sufficient to attract new visitors and, beyond that, to encourage residents to return? In any case, these efforts coincide with a gradual change in Japanese opinion about nuclear power. The radical opposition to atomic power that followed the 2011 disaster has given way to a more nuanced and pragmatic stance on the part of the public in the face of the energy crisis Japan is also experiencing as a result of the war in Ukraine.

Eric Rechsteiner