The leading regional daily paper has learned from its long history that it must continue serving its readers.

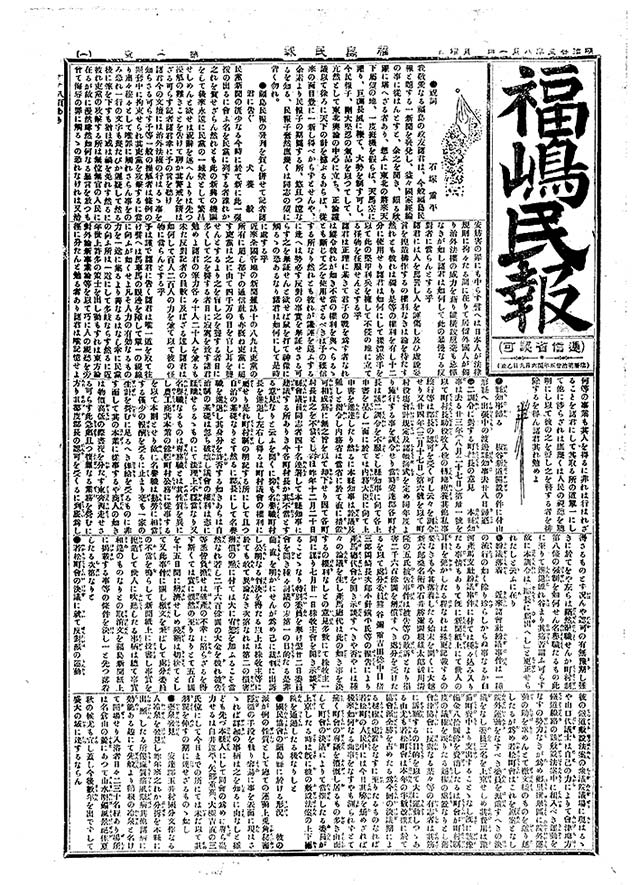

The Fukushima Minpo, the prefecture’s main daily, has illustrious origins as it was launched in 1892 by members of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement who pursued the formation of an elected parliament, revision of the Unequal Treaties with the United States and European countries, and the institution of civil rights. Local politician Kono Hironaka was one of the founding members of the Jiyuto (Liberal Party) in 1881 and contributed to the creation of the newspaper. It was only after WW2 that Minpo announced that it would break away from any political affiliation.

Though it is a member of both Kyodo News and Jiji Press, the country’s two main news agencies, the paper takes pride in producing most stories in-house without relying so much on “the agencies’ service as other newspapers from other prefectures usually do.

“Another pretty unique thing we have is the so-called Regional Development Bureau,” says Anzai Yasushi, Minpo’s editor-in-chief. “This bureau serves as a point of contact for readers and other groups in Fukushima and it is something that other companies do not have.”

To achieve this remarkable feat of editorial production, Minpo employs 120 reporters, 74 of them based at the Fukushima City headquarters and the rest distributed among the paper’s three main branches in Koriyama, Aizu Wakamatsu, Iwaki and other locations including a news department in Tokyo. All in all, Minpo has 325 employees.

“Until recently, we had almost no female reporters but in the last ten years or so many newly-graduated college students have joined the company and now half of our journalists, or even a little bit more, are women,” Anzai says. “In the past, we gave priority to men because the general opinion in the news industry was that women could not endure such gruelling working conditions. Now, on the contrary, they are considered an essential part of the paper and we value their contribution highly. Also, to be honest, it is true that, on average, women graduate with better grades and fare better in our employment examinations.”

Among the journalists who work at Minpo, there is also a reporter who specialises in horse racing, which is rare among local newspapers. “That reporter, Takahashi Toshiyuki, is my old high school classmate,” Anzai says, “which means he’s 58, like me, and there is nobody right now who can succeed him when he retires, so I do not know what is going to happen in ten years or so.” Fukushima attracts a lot of racing fans even from the surrounding prefectures because its racecourse, which dates back to 1918 and is just a 30-minute walk from the central station, is the only place in the Tohoku region where important horse races are held. “So it was decided to add a horse racing page to our sports section to provide information, predictions and results for its many fans,” Anzai says. “Even in our own company there are quite a few employees who are interested in horse racing, and when an important event is held, Fukushima’s inns, lodging facilities and restaurants are always crowded. Horse racing undoubtedly contributes to the city’s prosperity.”

Horse culture has a long history in Fukushima. Local breeders used to produce horses for the samurai and even after the Meiji Restoration (1868), several places in the prefecture provided horses for the military. During the same period, traditional horse racing, originally related to religious festivals, became more westernised and several facilities around the prefecture began to raise horses for racing and training. Horse-related festivals have survived to this day, the most popular being the Soma Nomaoi held every summer in Minami Soma.

Minpo has a circulation of around 222,000 copies and, according to Anzai, its readership is mainly comprised of middle-aged and elderly people who live in small towns, villages and mountainous areas. “They are our hardcore readers,” he says, “who have been reading our paper for many years and have continued to support us through the hard times. Before the earthquake and the nuclear accident, for example, we were selling more than 300,000 copies. After 3.11, we lost 60,000 subscribers in one stroke because of the evacuations. Then more people moved out of Fukushima and the population declined for many other reasons. But we are still the best-selling daily in the prefecture.”

Though circulation is down, distributing hundreds of thousands of copies day in and day out remains a difficult task, which is made even harder by a shortage of people. “In Fukushima, like everywhere else in Japan, newspaper distribution is entrusted to a system of small locally- based dealers who have contracts with individual companies to deliver their papers and collect money,” Anzai says. “It is a system that maintains Japan’s door-to-door delivery system and is the main reason for Japan’s high newspaper subscription rate. The problem is that fewer people are choosing to work as part-time delivery boys, and on top of that, the people who run these outlets are getting old and are difficult to replace.” As a result, in October 2021, there were only 14,276 dealers nationwide, a decrease of 4,560 compared to 10 years previously.

“To compensate for the loss of dealers, we are currently being helped by public promotion companies established by municipal governments and community development corporations. They commonly sell souvenirs and operate public facilities, but there are quite a few cases in which our company has managed to secure their help as distributors. The same has happened with the JA Group (Japan Agricultural Cooperatives). These are places where we can rely on a stable number of people.

“In large areas in the countryside or the mountains, where distribution is especially difficult and the cost of house-to-house delivery is higher than in urban areas, we pay the dealers a little extra for their efforts. Winter, of course, is the hardest season in this respect because the paper is delivered in the small hours and many roads are frozen, so we start printing earlier than usual to get copies to the dealers in time.” The internet is another way to make Minpo more visible to potential readers, yet Anzai confesses that his newspaper has been late in embracing digitalisation. “Even among other local dailies nationwide, I am afraid we bring up the rear,” he says. “Finally, last April, we launched the DX Promotion Department, and we are currently proceeding with the paper’s digitalisation. A new and improved electronic version is currently under development and will be ready by the end of this year.”

While recognising the need to adapt to the changing times, Anzai maintains that one of his company’s missions is to save hardcopies of the paper from extinction. “To state that many young people are moving away from the printed media is not correct,” he says, “because they have actually never even touched a newspaper. So, we want to create the conditions for younger generations to touch and read papers to show them how good they are. To achieve this, we are sending instructors to elementary and junior high schools around the prefecture to teach students how to read newspapers. In the last year, for example, we visited 130 elementary schools and 30 junior high schools. Hopefully, those students will become our future readers.

“We also encourage companies and organisations to get their employees to read newspapers. Some companies understand the importance of reading dailies and have agreed to buy a two- or three-month subscription for their newly hired employees in the hope that after this ‘trial period’ they will keep subscribing.”

Though the triple disaster has affected Minpo in many ways, Anzai does not think that the approach to reporting has changed after 3.11. “Basically, our mission remains to make people’s voices heard and report as best as we can on any issue of public interest,” he says. “Whatever the news, whether local or national, even if it is not in Fukushima’s interests, we are going to support our readers’ point of view.

“What has changed is our attitude towards those who are in power and how we hold them accountable. In the past, some of my superiors lamented the fact that Minpo was nothing but a public relations paper used by the elite to spread their slogans but, after 3.11, we were conscious that we had to write our stories from the perspective of the people, and that the national government and Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) had to take responsibility for what had happened. We may be a small local newspaper, but that does not mean we cannot fight on behalf of all those people who were affected by the disaster. I am proud to say that in our own small way we were able to effect change and make our voice heard around the country.”

While newspapers may have not changed their basic approach to reporting, Anzai admits that the extraordinary nature of what happened in March 2011 made them aware that they had to offer their readers something more than simple reporting. “A lot of people were evacuated and did not know what was going to happen to them or how they were going to survive in those terrible conditions,” he says. “In the immediate aftermath of an evacuation, many people were in desperate need of essential information such as where to get food and water. That is the kind of information we focused on, and we kept posting it as often as possible. After a month, those issues became less urgent, so we concentrated on the medical facilities that were available and able to respond 24 hours a day if you became ill. That experience came in handy in the following years when the prefecture was hit by floods, typhoons and more earthquakes, and we were able to put into practice the lessons learned in 2011 about how to deliver information properly in times of emergency. In that sense, I feel that we have become stronger and better equipped to provide a socially useful service.”

For Anzai, this service extends to helping other media outlets outside of Fukushima report on the prefecture. “After 12 years, it is inevitable that people from other regions will lose their interest in us,” he says. “Unfortunately, this means that they do not know what is currently going on. There are probably people who still think that there are many areas in Fukushima with dangerously high levels of radiation, just like after the earthquake; people who do not know that in fact the radiation levels have gone down significantly and that most areas are now safe.

Because our voice cannot be heard everywhere, it is up to other newspapers and magazines to provide the correct information, but I do not think they are doing enough.

“Sometimes they do not know how to access that information, so we help them. Just yesterday, a reporter from the Shimotsuke Shimbun in Tochigi Prefecture contacted me because he was working on a story for the March 11 anniversary and wanted to know about the current situation in Fukushima. We arranged for one of our field reporters to give him all the necessary information. If you contact us in advance, we can even guide you around the sites and help you understand what is really happening in Fukushima right now.”

When it comes to holding people accountable, Anzai is not shy about judging the work of local politicians, including Governor Uchibori, though his assessment in this case is pretty positive. “Uchibori has been a very close friend since he was sent to Fukushima by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and before he became governor,” he says, “and I think it was also thanks to him that the prefecture was able to recover so well. In particular, he is been very good at getting financial support from the government, and this has been key to realising our reconstruction plans.”

Now, however, there is a new problem in the form of the contaminated water containing tritium that TEPCO and the government are planning to release into the sea this spring and summer. If the water is released off Fukushima’s coast, many believe that rumours will start again and the population will suffer. That includes the people involved in the fishing industry. “The fishermen are not worried that the treated water will endanger the fish,” Anzai says, “because the fishing grounds will remain safe. What they fear is the consumers reactions: Will people in Tokyo and other parts of Japan stop buying their fish? This new crisis could inflict another huge blow on the fishing industry.”

According to Anzai, it is not that the treated water should not be released into the ocean. “Rather, we should come up with more ways to let the public understand that this is not just a Fukushima problem, but something that involves the whole country,” he says. “Governor Uchibori should embark on a countrywide PR campaign to say that the treated water is safe and there is no problem in Fukushima. Yet, in this respect, he has not done enough. I believe he can and should try harder so that the situation will not be misunderstood and that Fukushima is not victimised yet again.”

The Fukushima Minpo has done a lot to make sure that 3.11 is not forgotten, and its work has been recognised by the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association with two awards – one for a series of reports on the nuclear accident and another one, in 2014, for a series titled “Nuclear-Accident-Related Deaths: A Chain of Absurdity”.

“About 1,600 people in Fukushima Prefecture died in the tsunami and we have devoted stories to them so they will not be forgotten,” Anzai says. “About 400 people have contributed through interviews, and on the 11th of every month we publish a new article.”

Another project that started at the end of last year and is currently underway is devoted to the prefecture’s railway lines. “There are quite a few local railways in Fukushima,” Anzai says, “but many of them are in the red, and JR East is contemplating the possibility of closing them for good. Local railways play a really important part in the life of the local community, and we thought they deserved to be featured in our paper. We have already published about 30 stories, and we will probably reach 100 by this summer.”

Rail travel was badly affected by Covid-19, and even for Minpo the last three years have been very problematic. “Obviously, the pandemic made it almost impossible for our reporters to work as they could not interview people faceto- face,” Anzai says. “Of course, you can talk to them remotely, but it is not the same. I am sure the past three years were not easy for our reporters because they found it harder to collect data and information. One of the current challenges is to find a way to return to the old status-quo.

“On the other hand, the internet provided a way to hold our morning meetings and end-ofday editorial reviews online. This has been an unexpectedly positive development. Also, we realised that in order to keep the news machine going, we had to take infection control seriously. The main thing was to avoid the infection spreading among large clusters of people and putting an immediate stop to the paper’s production. We divided each section into smaller groups so even if someone became infected, the remaining members were able to continue working. This is a strategy we can use in the future when we are faced with a different infectious disease or a similar emergency.”

After 35 years of working at Minpo, the last three as its editor-in-chief, Anzai is somewhat ambivalent about the way his job has changed. “In the old days, the real thrill of being a newspaper reporter was frantically chasing after a special story or meeting someone in a bar around midnight for an interview,” he says. “There are not many reporters like that right now. The number of opportunities for such relationships to be built seem to be diminishing. Some of these changes have been for the better. The new rules, for example, state that overtime work should not exceed 45 hours a month. This has also made it easier for women to work in journalism. Yet, I cannot help feeling that it is quite difficult to write good stories and find a scoop under such conditions.”

Ultimately, Anzai looks back over Minpo’s long history and feels they should be proud of what they have achieved. “130 years ago when the first issue was published and Fukushima Prefecture had a population of 900,000, our mission was to become an ally to all of them,” he says, “and help them solve our social issues. The people who created Minpo aimed to achieve progress. This spirit has been handed down and nurtured for 130 years, and our paper has survived many ordeals, including a devastating earthquake and nuclear accident. In those first few days in March 2011 it was very difficult to secure enough paper and ink, so instead of the usual page count (between 24 and 32 pages), we only managed 16. But even during that period, we kept publishing without taking a single day off, and after one month we were able to go back to normal.

“Our goal is to produce the best regional newspaper in Japan and make Fukushima the best prefecture, and one way to achieve this is by supporting regional development and revitalisation.”

Jean Derome