This tradition imported from the West was rapidly embraced by the Japanese who love its warmth.

In December, as the days get gradually colder and shorter, illuminations take centre stage in every Japanese city after dark and Christmas songs can be heard everywhere. Japan has had a long love affair with Western culture, and Christmas is one of the Japanese’s favourite festivals.

It may seem odd that a non-Christian country celebrates Christmas. After all, only around 1% of the population claims Christian beliefs or affiliation, and all the main religious events revolve around it her Shintoor Buddhism. However, the Japanese are not only very tolerant when it comes to religion but have a long history of importing different cultures and customs from abroad and incorporating them into their life-style.

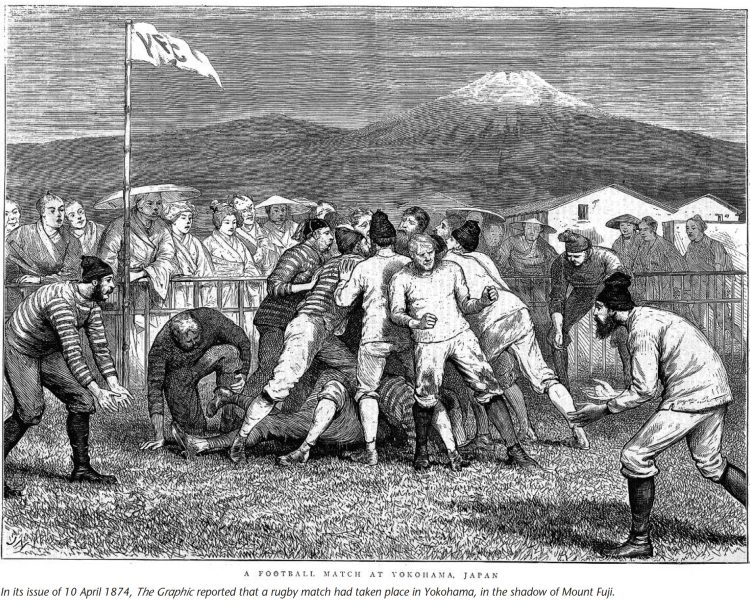

Though the wholesale import of Western culture only began in the Meiji period, Japan’s first significant contact with Christianity goes as far back as the 16th century. In 1552, in fact, Cosme de Torres, a Jesuit and one of the first missionaries to reach the Archipelago, invited Japanese believers to Suo Province (today’s Yamaguchi Prefecture) to celebrate what became the first Christmas Mass ever held in Japan. However, soon after that, Christianity fell out of favour with the authorities. In 1587, with the Bateren Edict, Toyotomi Hideyoshi banned all missionary activities. Then, following the Shimabara Rebellion (1638), the Edo shogunate killed 37,000 people, forcing the few survivors to practise their faith in secret, and banned Christianity for more than 200 years until the beginning of the Meiji era.

After the Portuguese traders and missionaries were expelled from Japan, the Dutch trading post in Dejima, Nagasaki, remained the only safe island where Christmas could be celebrated. On such occasions, officials of the shogunate and other Japanese people who had a connection with the foreign mission, such as Dutch scholars, were also invited. In addition, there were occasions when Japanese people living in Nagasaki who were well acquainted with the Netherlands also celebrated in imitation of their customs. Representatives of the Dutch trading post sometimes visited Edo, and it is said that the Tokugawa officials were curious about Dutch cuisine and culture, including the way they celebrated New Year.

Apparently Masaoka Shiki, one of the four great haiku (traditional 17-syllable poem) masters (the other three were Matsuo Basho, Yosa Buson, and Kobayashi Issa) was the first to mention Christmas in a poem. Shiki’s first Christmas-related haiku appeared in 1892 when he was 25 years old.

/ Meidi-ya

After Rohachi comes noisy Christmas

Rohachi is a Buddhist event in early December. At the time, Shiki seemed to think that after such a solemn event, Christmas was a little too noisy, and he was not fond of it. However, he quickly warmed to this festival, and in the next seven years, he devoted a haiku almost every year to what he began to regard as a joyful occasion. In this way, クリスマス (Christmas) became the first seasonal word in katakana (phonetic symbols) to be used in Japanese poetry.

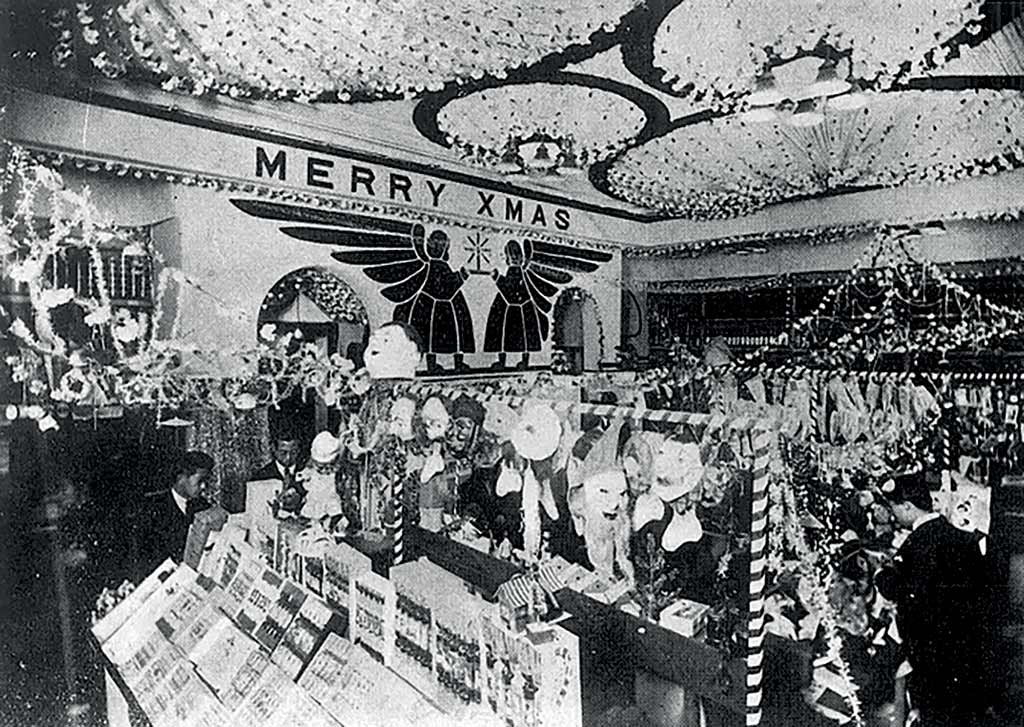

The pioneer of Christmas illuminations in Japan is said to be Meidi-ya, a high-end supermarket that used to be located in Tokyo’s posh Ginza district. Meidi-ya founder Isono Hakaru had studied in England and wanted to recreate in Japan what he had experienced abroad. The first Christmas decorations were displayed in 1900 after the store had moved from Yokohama to Ginza. The specific design at that time is unknown, but there is a photo of the storefront from the Taisho era (1912-1925). The words “MERRY XMAS” feature prominently on the elegant façade. On top of those, a sign that seems to depict Santa Claus welcomes visitors. Tanka (31-syllable poem) poet Kinoshita Rigen was another intellectual whose imagination was caught by the novelty:

Meidi-ya’s Christmas decoration lights sparkle and it starts to snow. This poem was later included in high school textbooks.

Meidi-ya’s illuminations caused such a sensation that people came from far and wide to see them, and other shops began to put up similar decorations. However, the shopping itself was still a limited affair since the gorgeous merchandise on display was off-limits for most families. Accordingly, the first Christmas shoppers were wealthy people with refined tastes and an interest in “exotic” Western culture.

Meidi-ya’s illuminations caused such a sensation that people came from far and wide to see them, and other shops began to put up similar decorations. However, the shopping itself was still a limited affair since the gorgeous merchandise on display was off-limits for most families. Accordingly, the first Christmas shoppers were wealthy people with refined tastes and an interest in “exotic” Western culture.

Regardless of the shopping, Christmas illuminations have continued to be a prominent feature of the holiday season. Nearly a century after Meidi-ya’s pioneering campaign, the Kobe Luminarie was held for the first time in December 1995. The city of Kobe had been severely damaged by the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in January of the same year, and a new event was organised to mourn the victims of the disaster and pray for the reconstruction of the city. In this respect, the light festival was regarded as a “light of hope” and a symbol of recovery. Although the Luminarie was originally planned to be a one-off event, its huge success led the organisers to turn it into an annual event with the aim of bringing tourists back to Kobe as their numbers had drastically decreased due to the disaster.

Appropriately held in the former Foreign Settlement, the ten-day festival regularly attracts more than three million visitors from around the country to admire the unique geometric patterns and decorations every year, which are designed and installed by an Italian company.

Starting with the Kobe Luminarie, the number of large-scale events aimed at revitalising the city centres and attracting tourists began to spread around the country. According to the Japan Illumination Association, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which consume less power than incandescent lamps, have become mainstream over the past ten years. Recently, a new type of “interactive” illumination that lights up when you step on it or changes colour when you clap your hands has become popular. As for Meidiya, it moved to Kyobashi a few years ago, about 500 metres from its old location.

Back to our historical excursus, in the Taisho period, boys’ and girls’ magazines introduced many Christmas-related stories and illustrations in their December issues. Also, in 1925, Japan’s first Christmas stickers (stamps given to people who donated to a campaign to eradicate tuberculosis) were issued.

Starting in the Meiji period, the government added two new holidays to the Japanese calendar. One celebrated the current emperor’s birthday while the other coincided with the day the former emperor had died. This, of course, meant that those two days changed with every new succession to the throne. As Taisho Emperor died on 25 December 1926, the holiday law was revised to create the Emperor Taisho Festival on that day. This coincidence further contributed to enhancing Christmas’s popularity in Japan in the following years. In 1928, for instance, the Asahi Shimbun, one of the country’s main dailies, wrote, “Christmas has now become an annual event in Japan, and children love Santa Claus”.

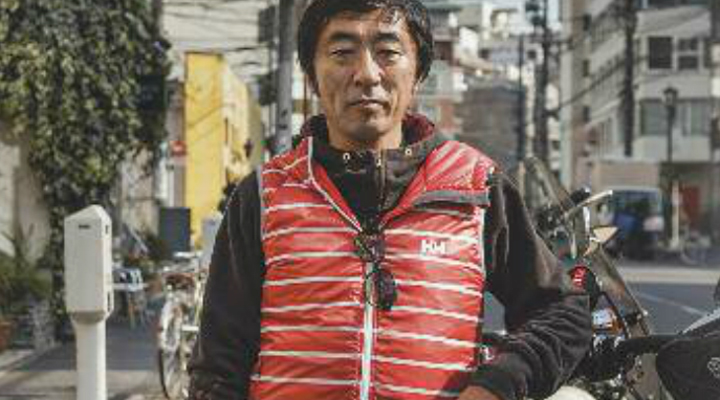

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

This situation lasted until 1948 when the holiday was abolished, and today, Japan is one of the countries in which, though the schools are closed because of the end-of-the-year vacation, 25 December is a normal weekday and people continue to work as usual.

In truth, there’s a movement to make Christmas a national holiday, the reasoning being that since Christmas is followed by the year-end and New Year holidays, it makes it easier for working people to use paid holidays and take longer vacations (until last year, by the way, 23 December was celebrated as Heisei Emperor’s Birthday). However, for many businesses, the end of the year is the so-called “busy season”, and most companies are against letting their employees take a break. In addition, it is difficult to turn a specific religious festival into a public holiday due to the principle of the separation of religion and State stipulated in the Japanese Constitution.

This, combined with the fact that the scale of the Christmas events are still relatively small compared to the rest of the Christian world, has created an interesting situation, which is potentially advantageous for the local tourist industry. In 2014 Skyscanner, a British travel site, began to recommend countries for people who “are not in the habit of celebrating Christmas with their families, are not religious, and want to avoid all the fuss and crowding related to the Christmas holidays”. In the list of the top ten countries to visit, Japan was ranked first, ahead of Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia and Algeria, Buddhist countries such as Thailand and socialist countries such as China.

In the early Showa period, many cafes in Ginza, Shibuya and Asakusa prepared Christmas menus, and the staff welcomed customers dressed in Christmas costumes. On 12 December 1931, the Miyako Shimbun reported that “Christmas will come to more than 7,400 cafes, and Santa Claus will be very busy”. The custom of dressing up for Christmas has survived to this day, and it is common to see cashiers in supermarkets and other shop assistants wearing Santa Claus hats and other fancy-dress costumes during that period.

The increasingly popular celebration began to appear in the most unlikely settings. For instance, in “Kato Hayabusa Sentotai” (Kato Hayabusa Battle Corps), a 1944 film directed by Yamamoto Kajiro, there is a scene in which a front-line dining room is decorated with a Christmas tree. The film was championed by the Ministry of War’s Sponsorship and Information Bureau and went on to become the highest-grossing blockbuster of 1944. Yet the censors did not bother to cut out a scene that clearly reminded viewers of Japan’s hated enemies and their culture.

However, after the war, the Taisho Emperor Festival was removed from the holiday calendar, Christmas quickly established itself as an annual event whose size and importance has gradually increased to this day. In the early 1950s, in particular, the so-called baby boom led to an explosion in births, and Fujiya, a nationwide chain of confectionary stores, created the prototype of the unique Japanese Christmas cake. After that, the Christmas sales season in department stores reached fever pitch, and Christmas became firmly established in Japan.

These days, Christmas sales are held as early as November. Street trees are decorated with miniature lights, Christmas songs are played in stores and Christmas cakes are sold in every bakery. Shops and offices hold events on Christmas Eve, while some families decorate the outside of their houses and their gardens with lights.

In many Western countries, 26 December is also a holiday, and the Christmas period ends on 6 January. In Japan, on the other hand, Christmas has nothing to do with religion (except for the tiny local Christian community) and is regarded instead as a commercial event. That is why, as soon as Christmas is over, the Japanese quickly put it behind them. The New Year’s Shinto-style decorations (e.g. the bamboo-made kadomatsu) replace the old ones and retail outlets display a new set of products. However, in recent years, there are places where the illuminations are left as they are until the countdown to midnight on 31st December.

It is true that culture, like humour, is often lost in translation, and Christmas is no exception. According to urban legend, for instance, there was a time when a Tokyo department store got things seriously mixed up and displayed a crucified Santa Claus. On the other hand, the trend of celebrating Christmas with fast food (particularly fried chicken) is real and probably unique to Japan, and never fails to elicit amused reactions from Westerners who are used to more lavish meals. Younger couples also tend to treat the celebration as a chance to spend time with their partners. In this respect Christmas Eve, in particular, has acquired romantic connotations.

According to a 2009 survey conducted by Printemps Ginza (a Tokyo department store) about how singles spent their Christmas Eve, 53% said they had a party with their family, while the remaining 47% went on a date with their partner. Another cultural element that is unique to Japan is Christmas Day’s connection to marriage. In the past, Japanese women were traditionally expected to marry at a young age, and ideally not older than 25. Because Christmas is celebrated on 25th December, those who were unmarried after the age of 25 were metaphorically referred to as “Christmas cakes” in reference to items that, if left unsold after the 25th, quickly lose their value. The term first became popular during the 1980s, but has since become less common because many Japanese women today choose to either marry at an older age or not at all, and still being single after the age of 25 is not so stigmatised.

Gianni Simone