Even without the religious dimension it has elsewhere, Christmas is an important time for the Japanese.

Foreign observers wonder why the Japanese love Christmas so much. After all, the reasoning goes, only 1% of the population is Christian. The fact is that though the Japanese are often portrayed as worker bees who do not know how to enjoy themselves, they certainly love to party, and Christmas offers a unique opportunity to have fun with family and friends. Christmas may not be a national holiday in this country, but that does not stop the Japanese from enjoying all the things that are associated with it, such as giving gifts, enjoying seasonal decorations and Christmas music and carols, having special meals, and for some people, even attending mass, if only to experience an exotic and – for most Japanese – baffling religious ceremony. What they do not do is exchange Christmas cards since they have their own local version, nengajo or New Year’s cards, which are delivered every year to houses all over Japan on 1st January by an army of part-time postmen specially recruited for this purpose.

As Christmas is usually a working day, many people party with friends in the evening or go home and celebrate with their families. According to a recent survey of Japanese men and women who were asked with whom they would spend Christmas, the great majority (60%) answered “family”. As for how to spend Christmas, “relaxing at home” was the top choice by far (66%).

In a November 2005 survey of a total of 474 internet users (single men and women living in Tokyo and three other prefectures) aged 20 to 39, about 70% answered that they wanted to spend Christmas with their partner. On the other hand, in 2006 the internet research company DIMSDRIVE surveyed women in their 30s on how they spend Christmas, and 43.5% responded that they were planning to have a party at home.

Since the 1930s, for those with partners Christmas has been a day to dress up, spend time together and exchange presents. In 1931, it was reported that many restaurants welcomed unmarried “unfortunate young people” by selling “one-yen” Christmas dinners (approximately 3,000 yen today).

Christmas’s association with romance was further boosted in the 1980s (the extravagant boom years of the so-called Bubble Economy) by a couple of hit songs, Yamashita Tatsuro’s Christmas Eve (1983) and Wham!’s Last Christmas (1984). Yamashita’s single became a Christmas standard when it was used in the railway company JR Tokai’s “Christmas Express” commercial (1988).

This long-selling hit is listed in the Guinness World Records, and its sales never fail to peak every Christmas season. A TV drama with the same title was broadcast in 1990, though it curiously did not include that song. Last Christmas is one of the ten best-selling songs by a foreign artist and has been covered by many Japanese artists, including Matsuda Seiko in 1991 and EXILE in 2003.

Other popular songs are Mariah Carey’s All I Want for Christmas Is You (1994), Matsutoya Yumi’s Koibito ga Santa Claus (My Lover Is My Santa Claus) (1980), and Shiroi Koibitotachi (White Lovers – “white” as in snow) (2001) by Kuwata Keisuke of Southern All Stars fame. Interestingly enough, most of these songs are about longing, missed encounters, heartbreak, or unrequited love. One song, for instance, is written from the perspective of a man reflecting on the happy times he has spent with a past lover, and reflecting on how often we fail to appreciate things until they are gone. Around the world, Christmas is synonymous with food and partying, two things the Japanese never fail to appreciate. In 1931, for instance, the Hochi Shimbun, a now-defunct newspaper, reported the following scene: (Boy A) I’m sorry, but what are you two doing all alone? (Girl A) Mind your own business! (Boy B) Why don’t we have dinner together? (Girl A) What impudence! (Girl B) Ah, that is fine as long as you guys are going to pay. (Boy A and B) OK!

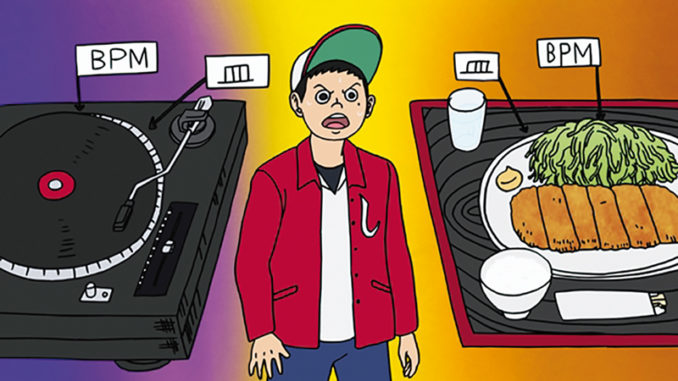

The article concluded that “In all of Tokyo, 12,300 turkeys are sacrificed for a merry Christmas and, sadly, killed”. When it comes to food, every country has its own traditions, which can even differ depending on the region, and though turkeys feature prominently in the above article, the Japanese have recently developed their own unique eating habits. In the United States, for instance, the custom of eating ham and turkey is widespread, and many people eat pies and ice cream, while Italians eat panettone, pandoro or other sweets that are only available during the Christmas holidays. In Japan, however, it is customary to eat chicken at Christmas. And not just any chicken, mind you, but Kentucky Fried Chicken. According to the company’s website, a successful advertising campaign in the early 1970s made eating at KFC around Christmas a national custom, and even today, its chicken meals are so popular during the holiday season that stores take reservations well in advance.

/ All Rights Reserved

In 2018, former KFC president Okawara Takeshi told Business Insider’s Japanese edition how he helped create this new tradition – and establish KFC as one of the leading fast food chains in Japan – through some creative thinking and a lie. When the first KFC outlet opened in 1970, it struggled with sales as passers-by were confused by the red-and-white striped decoration and English sign and could not tell what the restaurant was selling.

Restaurant manager Okawara was trying to come up with ways to boost sales when, one day in December, a nearby mission kindergarten asked him if he would like to play the role of Santa Claus because they wanted to buy fried chicken for Christmas and have a party. The event was so successful that other kindergartens asked him to organise Christmas parties for them.

Okawara decided to make the most of this new idea. His next move was to dress the Colonel Sanders doll in front of his store as Santa Claus. After all, to a lot of confused Japanese, the Colonel looked a little bit like Santa. Then he went a step further, promoting fried chicken as an alternative to American turkey dinners. As his efforts had made the news, Okawara was interviewed by NHK. Asked if fried chicken was really a common Christmas custom in the West, he lied and said yes. “I still regret that decision,” Okawara said, “but a lot of people seemed to like fried chicken anyway, so…”

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

There are alternative stories about how KFC came to monopolise the Christmas market. According to Yum! Brands, the American fast food corporation that operates KFC globally, expat customers who were missing their Yuletide turkeys at Christmas, realised that fried chicken was the next best thing for a half-decent Christmas holiday meal.

Whatever its exact origins, the canny Okawara passed the word on to his superiors, leading the company to launch its surprisingly successful “Kurisumasu ni wa Kentakkii!” (Kentucky for Christmas!) campaign in 1974. In the end, Okawara’s decision to combine KFC with Christmas took the chain from near bankruptcy to great success, and he went on to be appointed president in 1984.

Even today, celebrities such as actress Ayase Haruka appear in TV commercials and other ad campaigns to promote KFC’s hugely popular Party Barrel as early as late October. Company officials say that KFC records its highest sales volume each year on Christmas Eve. The restaurants are so busy that even back office staff, including the president and other execs, head out front to help on the day.

Indeed, for many people in Japan, Christmas Eve is even more important than Christmas Day. This is also somewhat true for children. This is because Christmas falls during the school winter vacation. Therefore, Christmas events at kindergartens, nursery schools and elementary schools have taken place before the holidays. In any case, you can not call it Christmas if you do not eat cake, and even in this respect, Japan has taken a different path. While Western countries enjoy fruitcakes, Yule logs (Swiss rolls) and sweet breads, Japan’s typical Christmas cake looks and tastes very different.

The history of Christmas cakes in Japan dates back to 1910 when the confectionery shop Fujiya was founded. They became popular when Fujiya began to sell them in Ginza, Tokyo’s central commercial district, in 1922. At that time, the effects of Westernisation were sweeping across Japan. Members of the wealthier classes in particular, had a strong penchant for Western culture in general and enjoyed Western-style desserts as a delicacy. So, being a Western-style dessert, Christmas cakes were associated with the idea of Western modernity and social status and became a major hit when they were commercially produced and became more affordable for the general public.

In modern Japan, typical Christmas cakes are sponge cakes usually coated with whipped cream or buttercream and decorated with sugar-crafted Santa Claus figures, Christmas trees, strawberries and chocolates. However, in recent years, manufacturers have begun to play with different shapes and styles and a wide variety of Christmas cakes can be found in the countless confectionery shops across the country. In some parts of Japan and South Korea, Christmas cakes are lit with candles, like birthday cakes and, in Japan, they are customarily eaten on Christmas Eve rather than on Christmas Day.

In any case, whatever their shape and appearance, today, Christmas cakes have established themselves as an essential element of the Christmas celebrations in Japan and symbolise, here as in the West, the act of sharing a good time with family and friends.

G. S.