/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Located an hour from Takamatsu, the island, once home to up to 400 brewe- ries, is seeking new markets.

Whether you love films, olive oil or soy sauce, there are many reasons to visit Shodoshima. And though you may have come to satisfy only one of your desires, it is quite probable that you’ll succumb to the other charms this island has to offer located off the coast of Shikoku, an hour away from Takamatsu by ferry. The journey across the Inland Sea is a reason in itself to visit as it allows you to grasp the full beauty of this region and enjoy the spectacle of all the islands the boat passes on its way to Tonosho, Shodoshima’s main port. The pandemic disrupted connections with Shodoshima since the island’s other port, Sakate, has been somewhat neglected although it serves the eastern part of the island where the soy sauce brewing district and the Movie Village are located.

Though buses do operate on the island, they are few and far between. So it is important to plan your trips around the island to be certain of not missing one of those rare buses used mainly by elderly people and school children. If you choose this mode of transport, it is best not to be afraid of walking as, unlike the train, the bus service is unpredictable. So it is advisable to hire a bicycle, which allows you to discover this amazing island at your own pace and without any stress. A couple of steps from Tonosho ferry terminal, next to Hotel Okido, is Shodoshima Cycle Station from where you can hire electric bicycles for the day for 2,000 yen (about £12), which will let you cycle the whole of the island’s 82-kilometre circumference or simply visit any places of interest, which are mainly located along its southern coastline.

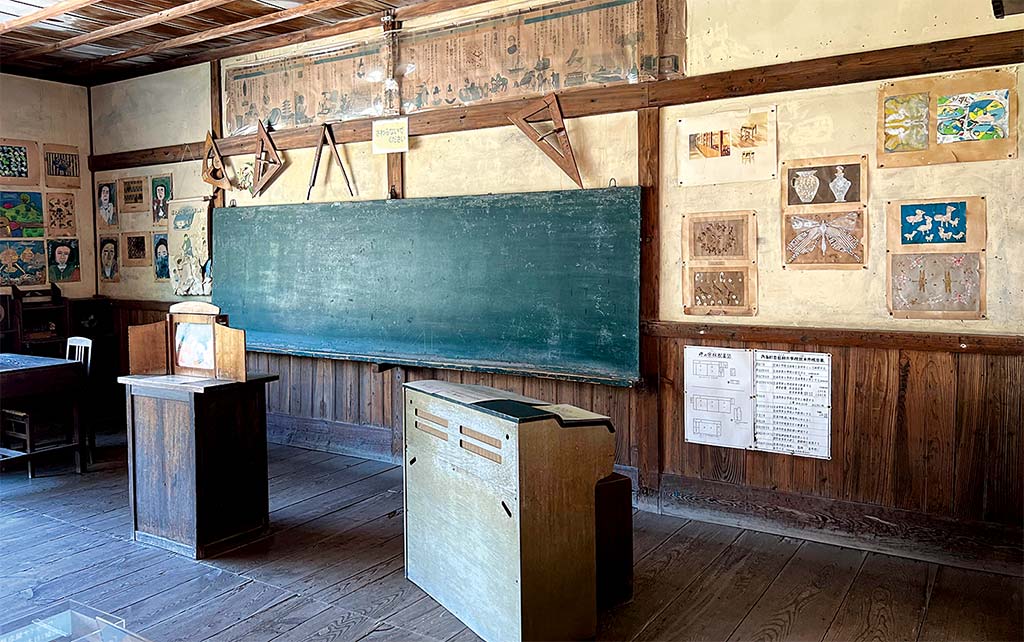

For many Japanese, Shodoshima is above all the setting for several major films including Kinoshita Keisuke’s Twenty-four Eyes (Nijushi no Hitomi, 1954) or Narushima Izuru’s Rebirth (Youkame no Semi, 2011), adapted from the novel of the same name by Narushima Izuru. The first is the best known and undoubtedly one of the most moving films ever made. It takes place in Shodoshima and tells the story of a young teacher, brilliantly played by Takamine Hideko who, in the lead up to the outbreak of the Second World War, is in charge of 12 pupils whom she meets again after the defeat of Japan. Besides the tragic character of this tale, which portrays the almost fatal damage inflicted on Japanese youth due to Japan’s involvement in the conflict with China and then with the United States, the film is a beautiful testimony to life on this island in the first half of the 20th century. It depicts both the hardship of daily life for the majority of the in- habitants as well as the importance of the soy sauce producers whose buildings are often fea- tured. To celebrate the film and to illustrate the island’s idyllic location for filmmakers looking for beautiful landscapes, the Nijushi no Hitomi Eiga-mura (Twenty-four Eyes Movie Village) was founded at the southern tip of the island, about a 15-minute bus ride from the port of Sakate. A reconstruction of the film’s famous classroom was built as well as a group of houses, some of which house film museums, while others are shops and restaurants. If you have not seen Kinoshita’s feature-film already, you can watch it for free in a small cinema theatre that reeks of the 1950’s with a bar on the first floor as well as a shop dedicated to cinema. Though the desire to promote film and film making in Shodishima is understandable, it is still rather surprising that it was felt necessary to reconstruct the film’s famous classroom when a visit to the original, perfectly preserved classroom just 500 metres away is included in the price of the entrance ticket (700 yen, just over £4).

/ Odaira Namihei for Zoom Japan

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

This wooden building dating from 1902 was used as a school until 1971. It is quite emotional to walk through the building, especially as several reminders of the film-shoot are on display. After this full-scale immersion into the world of cinema, there’s another journey back in time available when you visit Hishio no Sato (Home of Soy Sauce). Just 15 minutes to the north of the port of Sakate, the shoyu (soy sauce) brewing district is a very pleasant place to walk around. If you visit the Movie Village first, you cannot fail to miss the impressive factory of the Marukin company, the largest local producer whose size allows it to compete with global giant Kikkoman. To commemorate its 80 years in business, a museum was opened in 1987 in one of the largest buildings erected in Japan in the traditional gassho-zukuri style whose shape is reminiscent of “praying hands”. Built at the beginning of the Taisho era (1912-1925), it had been designated a National Tangible Cultural Property by the government. It was used as a pressing room for a long time, now it is where you can discover the history of the company, one of Shodoshima’s industrial flagships. At the exit, you can buy a soy sauce ice-cream, which is particularly tasty and refreshing on a hot day. Soy sauce production has flourished in Shodoshima for more than 400 years thanks to its perfect climate and equally favourable geographical situation. There were up to 400 brewers on the island at the beginning of the 20th century, which helped make it famous throughout the Archipelago. Though the number of producers has fallen drastically, the island continues to supply almost half of the production of Kagawa Prefecture, which is one of the five main manufacturing areas in the country. Nevertheless, the situation is far from easy for the twenty or so companies that continue to produce shoyu, and one way of helping them survive is tourists coming in search of authentic and outstanding products. One of them, Yamaroku Shoyu (1607 Yasuda, Shodoshima, tel. 0879-82-0666, http://yama-roku.net), is perhaps the most successful thanks to its history, its production methods and its open-minded approach towards other cultures. Today, headed by fifth-generation brewer Yamamoto Yasuo, the company founded around a century and a half ago has chosen to build on tradition to keep its head out of water in a sector where only 1% of the produce is aged in barrels. The visitor is welcomed by two huge cedar vats (kioke) where they can take a souvenir photo to impress their friends with the staggering size of these objects, which can hold up to 6,000 litres of soy sauce. Yamaroku’s owner and manager is even prouder in showing them off, as it is one of the only breweries in the country to make its own barrels, which are made with woven bamboo. “Unlike metal, bamboo is resistant to corrosion from salt and can last for 100 years without deteriorating,” he says. He thinks it important to travel around the country to meet other small scale producers who want shoyu to regain its previous status, now somewhat tarnished by being manufactured on an industrial scale. This certainly aids its widespread distribution, but leads to uniformity of taste and colour. “Aging it in wooden barrels is what gives soy sauce its depth of flavour. The difference is quite obvious when you taste it,” says Yamamoto. After visiting the small factory to see the different stages of production, you can taste Yamaroku’s range of shoyu products at a small stall facing the company’s offices. A bit like at a tasting in some sake breweries, you can compare the different products whose flavours and colours vary according to the length of time they have been aged in the barrels. It is hard work creating these exceptional products, and more physically demanding than you would imagine since the bulk of the work is apparently done by bacteria. However, in order for them to thrive, you need to optimise the process, which involves a great number of procedures, in particular regular manual stirring. Considering the vast size of the barrels, you can imagine the difficulty of the task. “I manage to lose up to 10 kilograms in two months,” says the boss of Yamaroku who goes into the sheds every day to check the progress of the manufacturing process, intervening when the need arises. His commitment to quality is motivated by wanting to ensure the continuation of the company, which is more than a hundred years old. He understands that producing a natural product like shoyu deserves to be taken seriously, as soy sauce helps enhance the flavour of a great number of culinary products.

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

He’s aware of the effort still needed to persuade the Japanese that soy sauce should be on par with sake in the taste stakes, especially those who are in charge of promoting Japanese cuisine around the world. Yamamoto has decided to open up to international markets. His website appears in English, which some of his employees speak, which enables the company to attract new customers. A video broadcast on the US website Business Insider in the spring of 1922 was also an important moment for the small company, which has seen orders pour in from all four corners of the world. Not all of the producers in Hishio no Sato are so enthusiastic, perhaps because they are part of an older generation. This is the case for Shiota Yosuke, owner of Yamasan Shoyu, a brewery founded in 1846 (142 Umaki-ko, Shodoshima, https://yamasanshoyu.co.jp). The buildings of his brewery bear witness to its glorious past, but what he says illustrates the many difficulties small breweries are facing today in order to cope with both falling consumption as well as competition from major producers capable of marketing products that meet the demands of customers who, for example, want less salty soy sauce.

Similar comments are made by Kindai Shoyu (833 Umaki-ko, Shodoshima, www.kindaishoyu.com) where Sakashita Tetsuya, aged 91, still keeps an eye on things despite the presence of his son Hideo who has finally decided to take over from his father. In order to survive, the brewer has chosen to rely on dashi shoyu, a blend of soy sauce, dried bonito, dashi (stock) and mirin (sweet rice wine), which Japanese housewives love for its strong taste and use to make soup. When walking around the brewery district you really get the impression that it is a world in decline. This is emphasised by the very few shops that remain open. But this is not unique to Shodoshima, it is an observation that can be made in many regions of Japan where young people are leaving in droves for the big cities as soon as they are able. Even more worrying, some tourist guides do not even mention this district, which was once the lifeblood of Shodoshima, preferring to focus on olive oil, the island’s other treasure.

The climate is ideal for growing olive trees, which is why they were introduced in 1908. Olive oil is now the number one product attracting Japanese visitors to Shodoshima. Located about 25 minutes from the port of Tonosho, Shodosima Olive Park (1941-1 Nishimura-ko, Shodoshima, www.olive-pk.jp) with its 2,000 olive trees is the place to visit if you also want to have a wonderful view of the Inland Sea and sample a variety of products made from olive oil. If you are looking for something authentically Japanese, you could give this place a miss because you will definitely get the impression of being in a Mediterranean country rather than Japan.

For a stunning view over Shodoshima and the Inland Sea, it would be better to head back along the road to Kankakei Gorge to the north of Hishio no Sato. Unless you have an electric bike, tackling the climb is not easy, but the magnificent scenery at the end of the cable car journey that takes you to the summit is worth all the effort in the world. Whatever time of year you visit, the ravines provide a dazzling spectacle, which experts consider to be one of the three most beautiful ravine landscapes in the country. More easily accessible, but requiring almost an hour-long walk, Goishizan, situated between the Twenty-four Eyes Movie Village and the brewery district, allows you to take in part of the island in one go, in particular its southern part and the Inland Sea. If you stay overnight on Shodoshima, it is worth going to watch the sun setting over this wonderful place. Take some onigiri (rice balls) with you and a little bit of soy sauce to spice them up. Another very good reason to visit Shodoshima.

Odaira Namihei