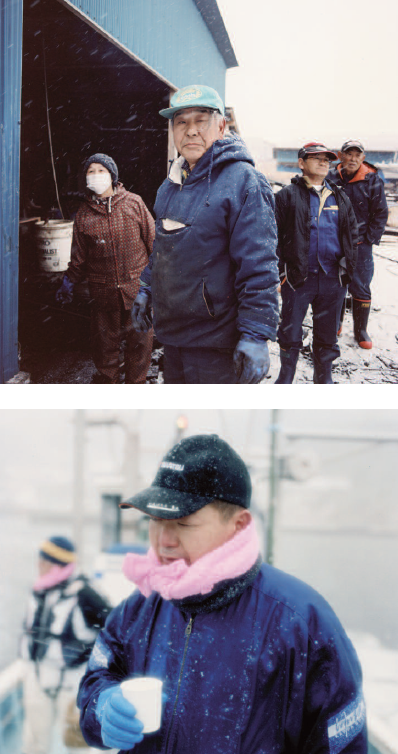

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Two key ingredients of Japanese cuisine have seen their popularity wane in Japan.

Washoku has conquered the world thanks to dishes such as sushi, tempura, soba and ramen. Many people are now familiar with traditional Japanese cuisine, which has the staple foods of rice, soup and pickles. However, other ingredients and seasonings play a major part in giving those dishes their immediately recognisable taste. Two of them, in particular, can be found practically everywhere: soy sauce and miso. Both of them have a strong umami flavour that comes from amino and nucleic acids produced by microorganisms in the fermentation process.

The origins of both soy sauce (shoyu in Japanese) and miso can be found in kokubishio, a salted condiment made from fermented soybeans, which was brought to Japan from Korea and China in ancient times. From this shared point of origin, they have followed different paths, eventually evolving into their present forms. Warm temperatures, abundant rainfall and high humidity provide good conditions for the development of a wide variety of fermented foods in Asian cuisines, and Japan has plenty of them. In order to preserve foods in an environment where the propagation of microorganisms easily causes spoilage, early inhabitants developed and refined a number of food preservation techniques such as drying, smoking, salting and, in particular, deliberate fermentation. By selecting benign micro- organisms that do not adversely affect flavour and allowing them to propagate, people in Japan and other Asian countries have managed to keep food safe from infestation by bacteria that could cause spoilage.

Fermentation not only preserves foods but also improves their flavour. A mould is deliberately added during the final stage of making fermented condiments such as miso, soy sauce and mirin (sweet rice wine). Today, fermentation may be less critical as a means of preservation, but it continues to be highly valued for the complex umami flavours it imparts to food.

Soy Sauce In Japan, it is believed that fish sauce began to be produced at the same time as rice farming began in earnest. Before long, however, grain sauce was introduced from mainland China and became mainstream. It is after the 7th century that the characters for soy sauce appear on record in Japan, though at the time they were read as “hishio”.

In the following centuries, shoyu production went through many permutations and today’s two main varieties reflect the difference in regional taste. Usukuchi soy sauce, which can be identified by its lighter colour and high salt content, was created in the latter half of the Muromachi period (1336-1573) in the Kinki region and, from the 17th century, Tatsuno (present-day Hyogo Prefecture), Osaka and Kyoto became the country’s main production areas. Kyoto, at the time, was the imperial capital and the locals tried as much as possible to keep soups and nimono (simmered dishes) lighter-coloured for aesthetic reasons. This called for lightercoloured soy sauce with sufficient saltiness. Today’s usukuchi soy sauce is made by adding larger amounts of salted water to maintain the moromi (unrefined shoyu) at a low temperature and limit melanoidin production. Sometimes amazake (a sweet and low-alcohol liquid made by adding koji, a type of mould, to rice to break down the starch into sugar) is also added to create a milder flavour.

The second and more popular variety, koikuchi, can be traced back to the mid-17th century. It was developed in places like Choshi and Noda in what is today Chiba Prefecture to satisfy the needs of the rapidly growing population in Edo (present-day Tokyo). Besides the feudal lords and their retainers who had to reside in the shogunal capital every other year, a large number of craftsmen moved to Edo to build the rapidly-expanding city. These people preferred strong-flavoured dishes, forcing the local restaurants and stalls into switching to the dark koikuchi soy sauce, which was brewed for over a year and had a rich flavour.

With time, the manufacturing method evolved and the quality improved. The years between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century were particularly important as the construction of larger factories led to a vast increase in production. Among the many technological innovations, Chiba-based Noda Shoyu (currently Kikkoman) devised a new manufacturing method by partially adopting chemical processing during the brewing process. Then, after the Second World War, the company introduced an even better method which shortened the brewing period and improved the efficient use of the raw materials. Both times, Kikkoman disclosed the patent to its competitors free of charge, helping improve the soy sauce industry as a whole.

Today, the domestic market has stabilised at around 160 billion yen* per year and is dominated by three major companies – Kikkoman, Yamasa Shoyu, and Higeta Shoyu. Together they account for half of the market. On the other hand, Japan remains a fierce battlefield with about 1,500 manufacturers – most of them medium-sized and small local brewers – fighting for survival.

Trying to diversify and get an edge on the competition, the smaller companies, often led by young brewers, are also those more likely to come up with new and exciting ideas. Wooden barrels are one of the hottest things in the soy sauce industry right now. Previously, the wooden barrels had been discarded in favour of plastic ones, to the point that barrel craftsmen were on the verge of extinction. However, a recent movement led by the younger generation is trying to revive this old practice. It is an interesting development because apart from keeping alive an important tradition, the shoyu produced in wooden barrels acquires new complex flavours which reflect the individuality of the brewery.

Always looking for niche markets that are too small to attract the attention of the major manufacturers, these new brewers have been coming up with new varieties including shoyu made with certified organic ingredients, shoyu made without allergenic soybeans and wheat, and even halal soy sauce.

Among other interesting recent trends, whole soybeans are making a comeback. Today most brewers, including the major companies, are using defatted soybeans, whereas high protein, mineral-rich whole soybeans make for a richer, mellow sauce, which is very different from the sharp-flavoured shoyu made from defatted soybeans.

Things have been changing in the packaging as well with the introduction of a soft, airtight plastic bottle, which has ushered in a new era for soy sauce. A long-standing issue with soy sauce has been how to prevent deterioration in quality, such as oxidation after opening. In particular raw soy sauce, which is not heated, is characterised by its mild aroma and bright colour, but its quality deteriorates more quickly than regular soy sauce, making it difficult to market. New plastic bottles are now equipped with a valve cap to prevent air from entering the container after pouring the soy sauce.

While the domestic market has not expanded in many years, the overseas market is booming as other countries, even in the West, are attracted to shoyu’s versatility and the possibility of mixing it with a variety of ingredients. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the export volume had been increasing at a brisk pace, with Kikkoman leading the pack again with 68% of the total of overseas sales.

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Miso Miso is made by mixing steamed soybeans, rice or other grains, koji and salt. This mixture is then fermented to produce a paste that can be kept for a long time without spoiling. The extended maturation process produces the brown melanoidins that give the finished miso its complex flavours. There are various types of miso. Pale in colour and lower in salt, white miso is made with more rice koji than other types. Although it does not keep as long as some other types of miso, it is prized for its distinct flavour. Miso is categorised according to the ingredients from which it is made. Hatcho Miso from Aichi Prefecture and other types of bean miso are made by adding koji to steamed soybeans (before salt is added) and the mixture is left to ferment and mature. Mugi miso contains barley in addition to soybeans and is especially popular in the western part of the country, including Kyushu and areas bordering the Inland Sea. Kome miso is made with rice; though this type is common throughout the country, it is particularly associated with Hokkaido and the Tohoku and Kanto regions.

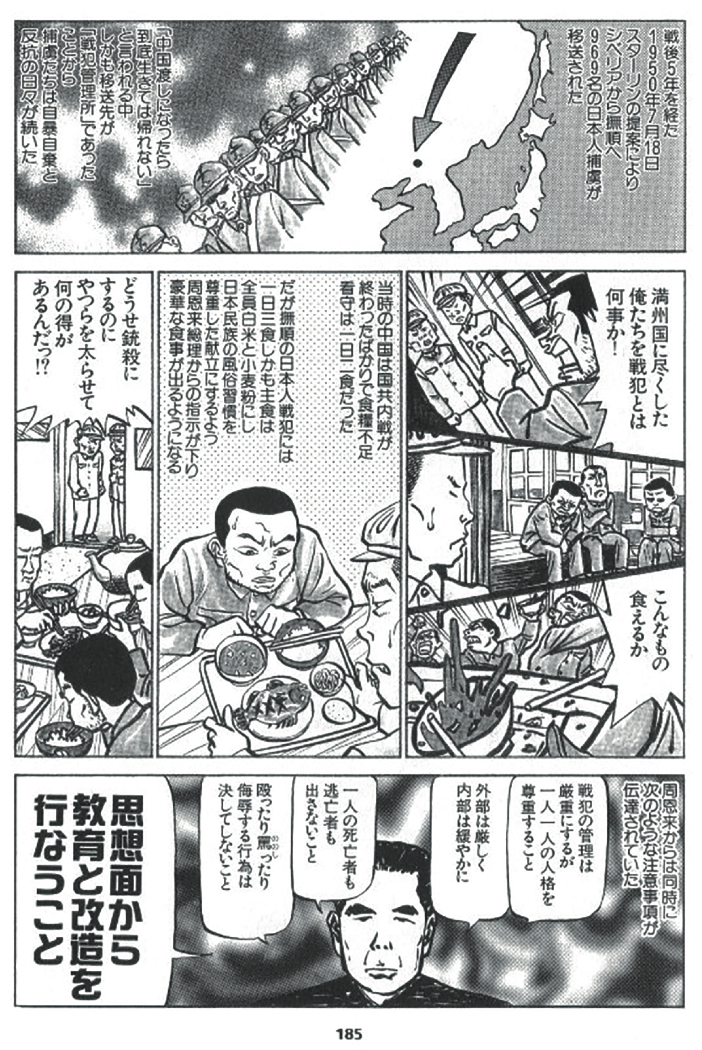

The word “miso’’ first appeared in literature in the Heian period (794-1185). In those days, it was not used as seasoning in cooking as it is now, but it was added to food or eaten as it was. Also, it was considered a luxury item and was paid as a salary or given as a gift to people of high status. During the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the samurai class rose to prominence, and the country went through a period of turmoil. Amid continued warfare the production of soy sauce in Kyoto, the imperial capital, declined and miso, which was easier to make, began to be used as seasoning.

It was during that same period that miso soup was first made in Japan, creating the basis of the samurai diet (rice, soup, side dishes and pickles). Originally considered a diet that emphasised frugality, it is now treated as a balanced eating style. In the following Muromachi period, soy bean production increased and miso finally spread to the people. It is said that most of the miso dishes that are still made today were created during this period.

The Muromachi period was part of the so-called Sengoku (Warring States) period, when various samurai warlords and clans fought to unify Japan under their control. During those years, miso became prominent as “war food”. At that time, miso was not only a seasoning but also a valuable source of protein. Since it could be easily preserved, it was dried or baked to make it easier to carry. Indeed, many of the preeminent feudal lords of the time, from Takeda Shingen and Date Masamune to Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, made it an essential part of their troops’ diet to the extent that they basically subsisted on rice and miso. For example, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi marched on Kyoto and conquered the imperial capital, his soldiers are said to have covered 230 kilometers in seven days, eating miso-flavoured rice balls. After Tokugawa Ieyasu unified Japan under his shogunate, the country experienced a prolonged period of peace, but miso further established itself as a staple of Japanese cuisine. With the population of Edo reaching 500,000, miso production could not keep up with the demand. Therefore, more and more miso was sent to Edo from Mikawa and Sendai, and miso shops prospered. In addition, the male population of Edo far outnumbered the females. All those men mostly ate out, leading to the creation of new miso-based dishes. Finally, during the Edo period, miso became part of everyday life and achieved a prominent position in daily meals, which has not been relinquished to this day. In this respect, research in food production and improved technology have helped manufacturers to come up with new ways to make, preserve and use miso. In terms of new products, many companies have recently introduced both liquid and granular miso (the latter produced by freeze-drying) in response to the new lifestyle of many Japanese.

Since many families no longer eat meals together, the tradition of making miso in a pot has decreased, and sales of instant miso soup are rapidly increasing due to people’s desire to enjoy miso whenever they like. The added advantage of buying liquid or granular miso is that it comes in slim bottle-shaped containers, which are easier to store in the refrigerator than the traditional square tubs of solid miso.

Another product that has become widely available in supermarkets is barley miso, a variety that is sweeter than ordinary miso because it contains a larger proportion of koji. Until now, barley miso used to be the monopoly of local miso makers, but the recent introduction on the market of similar products by major manufacturers has dented the earnings of mid-sized companies. Indeed, the gap between large and medium-sized miso makers is widening as the soaring costs of raw materials, labour and distribution are putting pressure on incomes, and the smaller companies are struggling to stay afloat.

According to the Food Supply and Demand Research Centre, miso production in 2018 decreased by 0.8% from the previous year to 478,068 tons (down 3,977 tons). In the miso market, the top ten companies account for nearly 70% of the sales volume, and among them, Marukome, Hanamaruki and Hikari Miso stand out. Although the sales volume of the market as a whole is on a downward trend, these three companies continued to exceed their previous year’s total in 2018.

According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, there are approximately 800 miso-related businesses in Japan, and the market size is 127.6 billion yen* based on shipment value. Due in part to the declining population, domestic shipments and consumption have either declined slightly or levelled off over the past few years. However, similarly to soy sauce, miso is experiencing an unprecedented global boom as exports have surged all over the world, from UK to Qatar.

Back in 1977, miso exports totalled 1,012 tons and 260 million yen*. Twenty-two years later, in 1999, the export volume had grown to 5,175 tons, worth 1.08 billion yen*. In 2010, it exceeded 10,000 tons for the first time and, in 2016, it reached a record high of 14,759 tons and a value of more than 3 billion yen*. According to the National Federation of Miso Industry Cooperative Associations (Zenmikoren), one reason for this unprecedented growth is the global Japanese food boom and the related increase in the number of Japanese restaurants abroad. According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the number of Japanese restaurants overseas stood at 24,000 in 2006, but rapidly increased to 55,000 in 2013 and 118,000 in 2017. It is nearly quintupled in just over 10 years. Asia has the largest number of restaurants with 69,300, followed by North America with 25,300 and Europe with 12,200. With so many Japanese restaurants, it is only natural that exports of soy sauce and miso would increase.

Even in terms of gastronomic culture, many EU countries are already familiar with fermented foods (e.g. cheese and wine), which makes them ready to accept miso as well. More surprisingly, a few Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar are among the top miso markets. These new developments have pushed miso makers into developing products for export including organic and halal miso. One company that has launched an aggressive overseas campaign is Hikari Miso, which ranks third in the industry in terms of sales. Headquartered in Nagano Prefecture, Hikari Miso began the contract farming of organic soybeans in the United States in 1993 and opened a sales office in Los Angeles in 2003. In 2012, it became the first Japanese manufacturer to acquire halal certification and now exports to more than 60 countries around the world.

Gianni Simone