/ Gianni Simone for Zoom Japan

Welcome to the hidden side of Kyoto, this often not easily accessible place is full of surprises.

The coast of the Sea of Japan is not exactly a memorable place. Its many coves, simple sandy beaches and rugged stretches of coastline possess a certain subdued beauty, but few people travel across Japan to see them. One notable exception is the sand dunes in Tottori. Another is the Tango Peninsula, also known as “Kyoto by the Sea”. The nickname may sound strange, but Kyoto Prefecture extends all the way to Japan’s western coast, and it is here that we find two one-of-a-kind places. Amanohashidate is a 3.6-kilometre-long sandbar that separates Miyazu Bay from the Aso Inland Sea. In list-crazy Japan, it is considered one of the three most scenic spots in the whole Archipelago (the other two are Matsushima Bay in Miyagi and Miyajima in Hiroshima), which means it attracts a steady stream of tourists. Amanohashidate first appeared about 6,000 years ago when sea levels rose and sandbars began to form on the seabed. Then a large amount of sediment flowed into Miyazu Bay due to an earthquake that occurred about 2,200 years ago. On a more regular basis, the Noda River carries down a constant amount of sand and gravel that collides with the ocean current.

In recent years, the sandbar has been in danger of shrinking and disappearing due to erosion as a result of changes in the ocean current in the bay. In order to prevent what would have catastrophic consequences for local tourism, the government has installed a large number of small sedimentation dikes on the right side.

Most travellers, on getting off at Amanohashidate Station, take the monorail up Mount Myoken to View Land, a diminutive amusement park from which they get a fine panoramic view of the blade-like sandbar slicing through the bay and extending out towards the horizon. From up there, the sandbar looks green because it is almost completely covered with thousands of pine trees.

The other reason for climbing to View Land is to witness tourists performing “mata nozoki” i.e. standing near the edge with their back to the sea, spreading their legs then bending forward and sticking their heads out through their legs. Seen upside down, the sandbar looks like a Bridge Floating in the Sky (that is what Amanohashidate means). Or a dragon soaring up into the sky. Or so they say.

According to mythology, when Izanagi and Izanami (the legendary creators of the Japanese archipelago) were born, they stood on the Floating Bridge and lowered the Heavenly Spear into the sea. When they lifted it up, the falling drops piled up to form an island.

Mythology aside, Amanohashidate began to be recognised as a place of scenic beauty in the early 8th century, while in 1643, writer and philosopher Hayashi Shunsai began to sing the praises of Matsushima, Miyajima and Amanohashidate. Visiting in summer offers the added pleasure of bathing in these waters. In fact, the right side of the sandbar has a long beautiful beach, and the sea is idyllically calm and peaceful. Just beware the crowds of tourists, which are far larger than the view from the hill might suggest. Or you could opt either to walk part or the whole length of the sandbar, while taking cover under the shade of the deep green pine trees.

Tango’s other jewel is further up the peninsula and can only be reached by car or by catching one of the infrequent buses. Indeed, the steep coastline precludes any train lines from venturing up there, only allowing the construction of a narrow road squeezed improbably in between the sea and the mountains.

Though the peninsula looks rather inaccessible from the rest of Japan, it used to be an important point of contact between the Imperial court in Kyoto and China. During the Asuka Period (592-710), Tango became an active international trade hub, and in a local burial mound archeologists have unearthed the oldest Chinese copper mirror ever found in Japan, dating from 235 AD.

The east coast road finally takes us to Ine, a small fishing village that is home to a unique kind of architecture. In Japan, life by the sea means flirting with disaster because of the constant threat of earthquakes and tsunamis. However, the mouth of the small cove where Ine is located faces south, away from the open sea, and an island almost completely blocks the mouth of the bay, acting as a natural breakwater. Moreover, the difference between high and low tides is about 50 centimetres a year. All these factors contribute to the harbour’s safety.

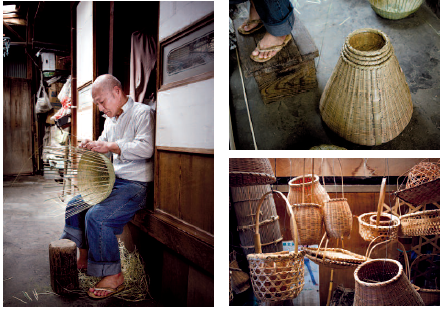

This fortuitous geography has allowed the local fishermen to build habitable boathouses directly over the water since the early 18th century. Today, 238 verified boathouses, or funaya, as they are called, are spread along the five-kilometre shoreline, and a boat tour offers a chance to appreciate the ingenuity of the fishermen and learn about Ine’s history.

All the funaya have been built following the same model, but each one of them looks slightly different. The living quarters are a floor above the landing area, storage space and workshop, which is on the water itself. About 90% of the gabled buildings were built with the gable side facing the sea, and the landing area was constructed with a slope so that the fishermen’s wooden boats could be pulled out of the water. The workshop is used to prepare for fishing, the maintenance of fishing boats and fishing gear, drying fish, storage of agricultural products, etc. The base and pillars are made of castanopsis, a kind of wood similar to the chestnut tree, while the beams are made of pine logs. Like many other small towns and villages, Ine’s population is gradually aging and shrinking. Until the mid- 50s, it hovered at around 7,000-8,000, but since the 1960s, it has declined at an increasingly fast rate. According to the 2010 census, for instance, 2,412 people lived in Ine. In 2022 they were down to 1,984.

Ironically, this demographic crisis has coincided with increased interest from the media and a remarkable boom in tourism. It started in 1982 when Yamada Yoji chose the town to shoot some scenes of Hearts and Flowers for Tora-san, the annual instalment of his famous It is Tough Being a Man series. Ten years later, it became the location for Kuriyama Tomio’s Tsuribaka Nisshi 5, another popular film saga. More recently, in July 2005, Ine was selected as an Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings, becoming the first fishing village in Japan to be honoured with this title.

Thanks to the hype, hundreds of thousands of tourists visit Ine every year to enjoy the scenery, eat the local fish, and spend a night in one of the many funaya that have been turned into traditional inns.

G. S.