Since it opened to trade, this port city has served as a gateway to the cuisines of the world.

The Japanese are curious eaters and have always welcomed foreign food with open arms. Nowadays, they nonchalantly alternate their traditional diet of rice, fish, pickles and miso soup with bread, meat and a vast array of dishes from abroad.

Japan’s love affair with Western food goes all the way back to Matthew Perry’s arrival in 1853. When the American commodore invited the Japanese delegation to visit one of his ships, he threw a party that left the four commissioners amazed, delighted and very drunk.

In “Yankees in the Land of the Gods”, Peter Booth Wiley says that “the commissioners were most impressed with four large cakes that bore their coats of arms. Whatever food was left over was carefully wrapped and stowed inside their kimonos”. At the end of the party, “one of the commissioners, in a jovial mood after consuming whisky, punch, Madeira, and champagne, threw his arm around Perry’s shoulder and leaned his head affectionately on his epaulette, repeating again and again, ‘Nippon and America, all the same heart’”. Then, after signing the treaty that made Japan’s opening to foreign trade official, Perry threw a dinner party – a gorgeous affair that included raw oysters, mushroom soup, boiled pears, eggs boiled, pressed, and cut into strips, boiled bream, crawfish and shrimp. You could say that the Americans won the hearts of the Japanese through their stomachs.

Between the end of the shogunate (hereditary military dictatorship) and the beginning of the Meiji period, more and more foreigners travelled to Japan, and the “big bellies” of the crews of the ships arriving in Yokohama, the garrisons stationed there, and the residents in the foreign settlement resulted in a great demand for food supplies. Items that the Japanese were unable to supply, such as beer, meat, milk, bread and vegetables, had to be produced by the foreigners themselves.

They started growing vegetables as early as the 1860s. One of the places chosen was the historic neighbourhood of Yamate, known as ‘The Bluff ’ in English, where they also raised pigs. Later they began to cure hams in the nearby village of Kashio in the Kamakura district (this was the origin of the now-popular Kamakura Ham brand), while in the spring of 1860, Eisler and Martindell opened Yokohama’s first butcher’s shop.

Speaking of meat, an early popular dish was gyunabe (beef hotpot), a version of sukiyaki made with tofu, spring onions and other vegetables. According to certain sources, this dish was being eaten in Nagasaki as early as 1854. However, the opening of the port of Yokohama led to increased demand, so much so that in 1864, the shogunate approved the opening of a cattle farm on Kaigan street. A year later, at the request of the foreigners, the authorities set up a slaughterhouse in Kominato, on the outskirts of the city.

The best way to taste this old-style dish today is to head to Araiya, which has been in business since 1895. To begin with, most restuarants cooked it with miso soup to reduce the beef ’s strong taste. Araiya, however, preferred sweet soy sauce, and this has remained its trademark to this day.

Western food, particularly meat, was seen as a symbol of modernity and civilisation, but rice remained Japan’s staple food. In the end, the two ingredients met in the 1890s to create another extremely popular dish, gyudon. The name says it all: put rice into a big bowl (donburi in Japanese), top it off with a generous serving of beef (gyu) and you have gyudon. Nobody knows who the first person to come up with such a simple yet ingenious idea was, but like gyunabe, it spread like wildfire, especially in the Tokyo working-class districts of Nihonbashi (where the first general fish market was located), Ueno and Asakusa, where it became a favourite street food. Japan’s original gyudon chain, Yoshinoya, began in 1899 and attracted a loyal clientele with the motto “Tasty, low-priced, and quick”.

Gyudon may have originated in Tokyo, but today’s biggest chain, Sukiya, started in Yokohama. Zensho Holdings’ founder Ogawa Kentaro had worked at Yoshinoya since 1978, but, in 1982, he left the company and opened a shop near Namamugi Station, in Tsurumi Ward, targeting workers in the Keihin industrial area.

He first tried to sell bento (lunch boxes), but quickly switched to gyudon. Even today, while other gyudon restaurants can mainly be found outside stations and downtown areas, Sukiya’s main focus is suburban outlets located along the main roads.

Though the company headquarters moved to Tokyo in 2001, Sukiya maintains strong bonds with Yokohama. Whenever possible, the typical Sukiya roadside store sports the same standard design featuring a red brick-like wall with a clock tower on the roof. The brick wall is a reminder of Yokohama’s Red Brick Warehouse – one of the city’s landmarks – while the clock tower is similar to that of the Yokohama Port Opening Memorial Hall. The clock tower, by the way, is also used to decorate the beef bowls. The name Sukiya is a combination of sukiyaki and suki, the latter word meaning “like” or “love,” and customers sure love this company. Indeed, Sukiya is currently Japan’s biggest gyudon chain with 1,936 outlets nationwide. If we add the other three major companies (Yoshinoya, Matsuya and the latest addition, Nakau) we have a grand total of 4,575 restaurants (as of 2020). And that figure doesn’t include independent restaurants and other smaller chains operating in certain areas. If we consider that the number of McDonald’s branches in Japan was about 2,900 in 2018, gyudon must be considered a major presence in the highly-competitive Japanese fast food market.

If gyunabe and gyudon have humble origins, the next two dishes first appeared in one of the poshest hotels in Japan, the Hotel New Grand. It opened as the Yokohama Grand Hotel in 1873 under British management, but was badly damaged in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and rebuilt in 1927.

In 1930, the hotel’s chef was Swiss-born Saly Weil. One day, he had to improvise a dish for a sick guest and came up with what would become known as shrimp doria: buttery cooked rice with prawns in a creamy mornay sauce baked in the oven. Weil’s impromptu creation was so successful that it not only became one of the hotel’s specialities, it was quickly copied by other restaurants and has become a staple of socalled Japanese yoshoku (Western cuisine).

The next “Western-style” dish appeared after the Second World War, when the U.S. Army occupied Japan and thousands of troops arrived in Yokohama (General McArthur himself spent his first three days in Japan at the Hotel New Grand, which had miraculously survived the air raids). The hotel’s chef noticed that many American soldiers were eating spaghetti with ketchup and decided to improve on what he considered a bland, unappetising concoction, finally creating what is one of Japanese kids’ favourite dishes today, Spaghetti Napolitan. The Hotel New Grand still offers gorgeous and pricy versions of these two dishes. They are also widely available in much cheaper restaurants.

Nowadays, bread – the British loaf variety – can be found in every Japanese home. But during the Meiji period, it was an expensive food that only wealthy people could afford. Interestingly, the first bakery of sorts was started by a Japanese, Utsumi Heikichi, the son of a confectionary owner. Around 1860, he learned the trade from the ship’s cook on a French warship and opened his own shop. However, his bread was more similar to dumplings or Japanese manju (steamed filled wheat dough) than traditional loaves.

The following year, American George Goodman and Jose Francisco from Portugal opened the first proper bakery. Englishman Robert Clark ran the Goodman shop for a while before opening his own shop, Yokohama Bakery, in 1865. This is how British pan-style bread became mainstream in Japan.

When Clark returned to Britain in 1888, he left the business to his assistant, Uchiki Hikotaro, who had been working at the bakery since he was in his teens. Uchiki moved the shop to the Motomachi district, the same address at which it is located today. They sell many kinds of sweet rolls and buns and even French baguettes, but their signature bread is still a pan loaf, which happens to be called “England”.

The restless Carlisle left Japan the following year in search of new adventures, but the Japanese were once again quick to follow his example. Machida Fusazo was a member of the diplomatic delegation that had travelled to the United States in 1860 to exchange treaty documents with the American government. Tasting ice cream for the first time, he was so impressed that he learned how to make it and in 1869 opened a shop in central Yokohama Hyomizuya where he sold what, at that time, was called aisukurin. Instead of China, Machida got his ice from Hakodate, in Hokkaido, and used raw milk, sugar and egg yolk to make a product similar to today’s custard ice cream. However, those ingredients were not cheap, and few people could afford Machida’s hand-made aisukurin as it cost the equivalent of 8,000 yen today. We have to wait until 1879 for another foreigner, American Albert Wartles, to establish Japan’s first ice-making factory, the Japan Ice Company. Its location? Why, Yokohama of course, near today’s Motomachi-Chukagai Station.

Carlisle and Machida’s pioneering Yokohama shops are long gone, of course, but near the site of Machida’s shop, the Japan Ice Cream Association has installed a monument to commemorate the event: the statue of a mother who is about to breastfeed her baby. As for the real thing, it is available at Yokohama Bashamichi Ice, located inside one of the two Akarenga (Red Brick) Warehouse shopping malls. We cannot finish our short tour of Yokohama’s culinary tradition without mentioning ramen, a noodle dish that entered the country in the mid-19th century through the newly-opened port towns. Yokohama, in particular, had a growing Chinese community, and the first chukamen (Chinese noodles) outlets appeared in Chinatown before gradually spreading to other places around Yokohama and Tokyo during the Taisho period (1912-1925). In the next 100 years, different regions developed their own versions, from Hokkaido’s miso ramen to Fukuoka’s Hakata-style tonkotsu (pork bone-based soup). Yokohama’s iekei ramen is a relatively recent invention. It was created in 1974 by Yoshimura Minoru, a long-distance truck driver who had acquired vast ramen-related knowledge on his trips around the archipelago.

One day, Yoshimura came up with the idea of combining Hakata ramen’s creamy pork broth with the clear chicken and soya sauce soup of Tokyo’s shoyu ramen, and after an apprenticeship at the influential chain ramen shop, he opened his own small ramen shop, Yoshimuraya, near Shin-Sugita Station in Yokohama’s Isogo Ward. It was located in an industrial area with heavy traffic and a high footfall and became an instant hit with factory workers and truck drivers. Today’s ramen scene is rapidly evolving and “gentrifying” with the introduction of new, delicate fish and seafood broths aimed at more refined palates, and iekei ramen tends to be overlooked, probably because of its blue-collar origins. However, it is still very popular among hardcore ramen fans, one reason being that customers are able to specify the firmness of the noodles, the amount of fat in the soup, and the strength of its flavour. Iekei shops also offer a great number of free toppings and seasonings – garlic, pepper, ginger, sesame seeds, chilli paste, vinegar – to customise the taste.

Iekei ramen shops – especially the chains – can be hit and miss, but if you are in Yokohama, you should visit the place that started it all, the original Yoshimuraya, which in 1999 moved near to Yokohama Station’s West Exit. You won’t be disappointed.

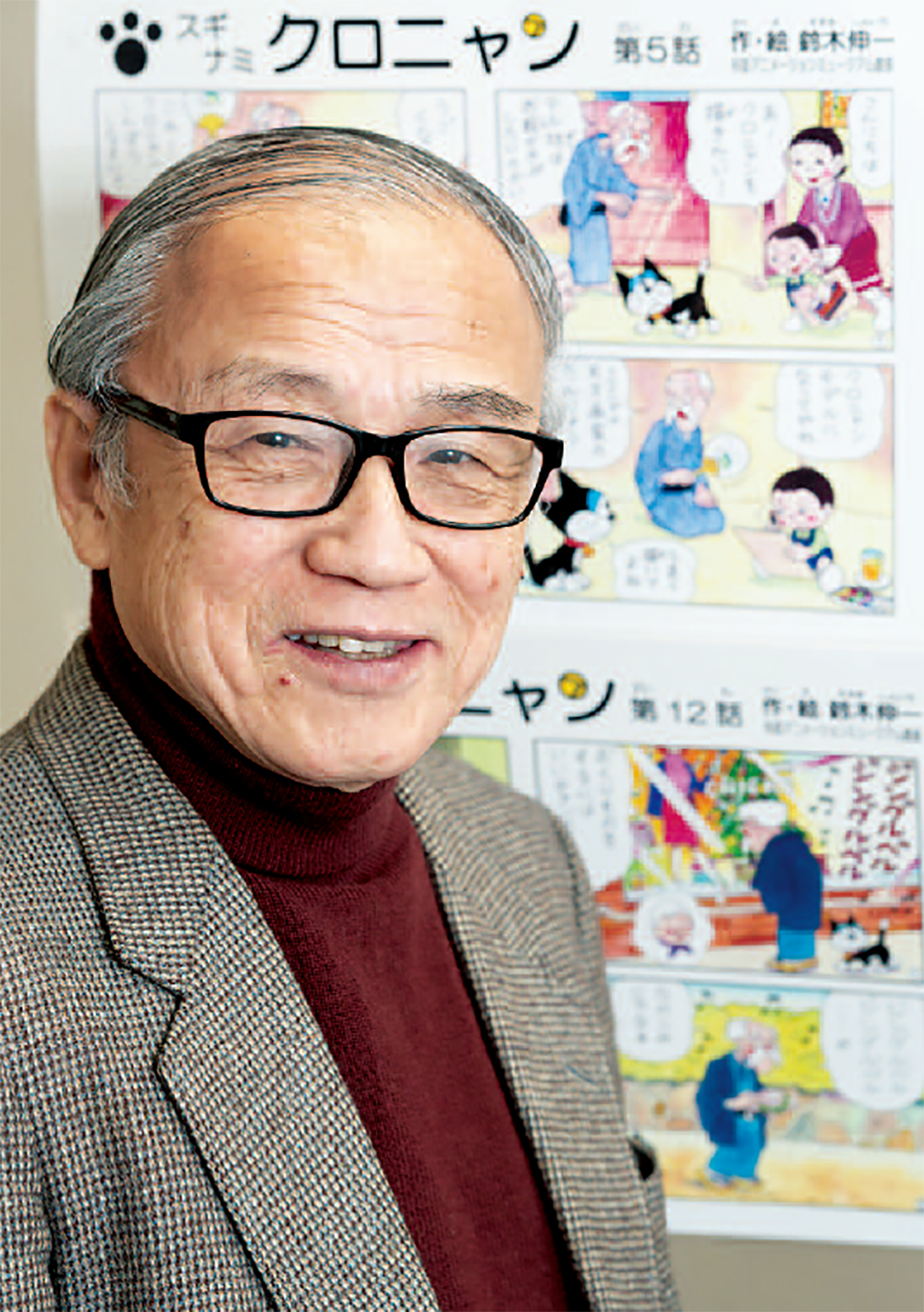

If you feel like digging deeper into ramen history, the Shin-Yokohama Ramen Museum offers lots of information and a replica of an old downtown area circa 1958 where you can sample dishes from around the country. Or you can head to the Cup Noodles Museum in central Yokohama. Instant ramen is an extremely popular kind of fast food in Japan, and this museum celebrates the life of Ando Momofuku, Nissin Foods’ founder and the man who invented chicken ramen and instant noodles in 1958. Granted, the birthplace of cup noodles is Osaka, but this museum is another fun way to experience yet another important aspect of Japanese culinary history. There is even a workshop where you can make your own cup noodles.

Gianni Simone