Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Though interest in the topic has declined over time, historian Kishi Toshihiko continues to keep it alive.

What remains today of Japan’s relationship with Manchuria, the Chinese region that 90 years ago played such an important part in its history? To solve the “Manchurian Mystery”, Zoom Japan turned to Professor Kishi Toshihiko, a researcher at the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, whose research covers 20th-century Asian history, East Asian regional studies, and media studies.

Do you feel that the Japanese know the history of Manchuria during the Japanese colonial era? Kishi Toshihiko: I have to say that interest in the history of Manchuria is low. To begin with, the number of people who have direct experience of that period is decreasing rapidly, and most of the postwar generations know very little about Manchuria and Manchukuo. For the younger generations, not only Manchukuo but even prewar history and war-related memories are regarded as being in the distant past. On the other hand, as far as researchers and the publishing world are concerned, there is a tendency for the younger generations to approach the reality of Manchuria from the perspective of post-colonialism and modern colonialism. I think that those whose relatives lived in Manchura, e.g. their grandparents’ generation, and the second and third generations of the orphans who remained in China after the war, are particularly interested. That’s why we, as researchers, are trying to find ways to pass on these memories to future generations.

I wonder what Kyoto University students think about this subject. K.T.: You could say that our students are a little different from most people their age. First of all, they are very knowledgeable and have a keen interest in these subjects. Also, as you know, while the University of Tokyo has a more orthodox approach to history, we do things differently and our students tend to think outside of the box. This is the ideal place for them to pursue their interests because Kyoto University is the centre of research on Manchurian studies.

This year marks the 90th anniversary of the founding of Manchukuo. What can we learn from this chapter of Japanese history? K.T.: The state of Manchukuo lasted for 13 years, from 1932 to the end of the war. They were aiming to create a state-controlled experimental nation that would later become a leading model for the establishment of Japan’s National Mobilisation system when the Pacific War broke out in 1941; a society with a state-controlled economy and a strict censorship system born from the strong relationship between business, the political elite, and the military. I think the Manchukuo experience is a good case study from which we can learn many things about today’s authoritarian states and one-party dictatorships. In this respect, studying the way Manchukuo developed can help us to understand the way in which the political systems of China and Russia work.

What was the motivation for Japan to invade Manchuria? K.T.: The Japanese are prone to obey orders and follow what they are told from above. Authority figures are treated with deference, and whatever they say is often accepted uncritically and becomes a slogan behind which people rally. In this particular case, three days before the Manchurian Incident, Matsuoka Yosuke proclaimed that “Manchuria is the lifeline of our country”. Matsuoka was the former Deputy Governor of the South Manchuria Railway Company and his words played an important role in determining how events unfolded in China. He became the spokesperson for all those groups that saw Manchuria as Japan’s new frontier: the political and business elite, for example, aiming to acquire resources and develop the country’s heavy chemical industry; the Army, which wanted to strengthen Japan’s defences against Soviet communism and the Republic of China; and the bureaucracy whose plan was to realise a wartime-controlled economy. Yet it was not just the elite that saw an expansion in Manchuria as a positive thing. The press, for example, were struggling to sell copies under the regime of censorship, and saw Japan’s expansion into Manchuria as a way to increase their readership. Also, workers dreamed of earning high salaries by working overseas for the South Manchuria Railway and other companies. More generally, many people were swept up by a desire to see their country follow in the footsteps of the Western imperialist states. It was an era in which practically everybody believed that Japan was right, and they were eager to support such foreign policy. This mentality lasted until they lost the war.

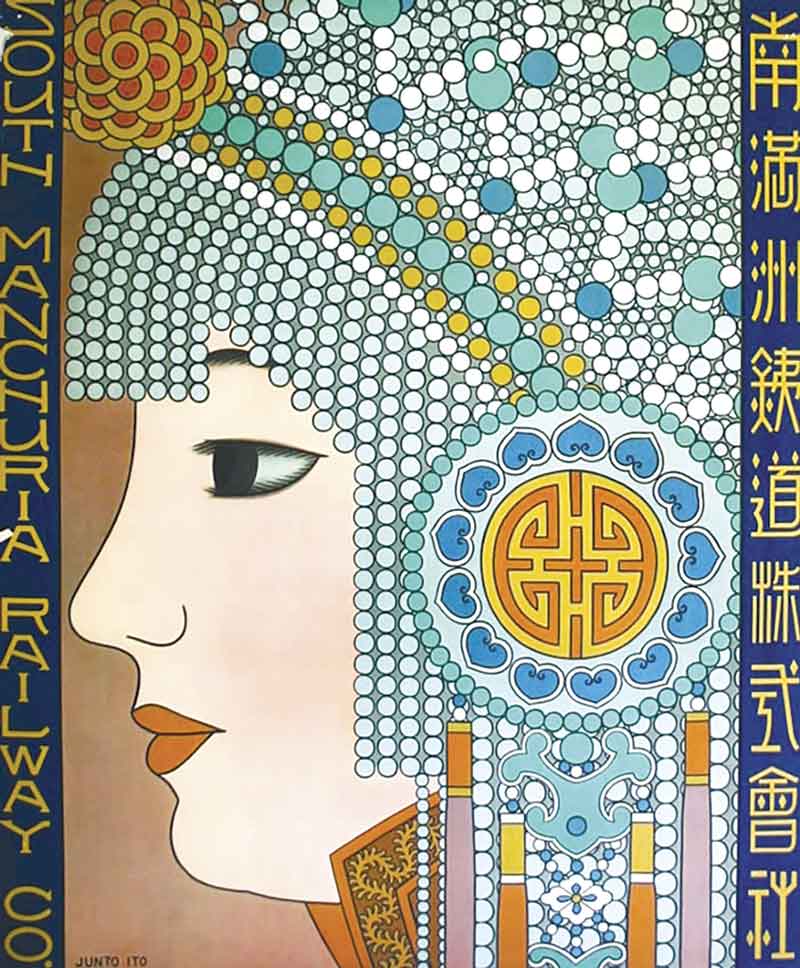

Manchukuo Propaganda Posters & Bills, Prof. Toshihiko Kishi’s Laboratory, Kyoto University

I guess popular expectations to find good jobs and new economic opportunities played a decisive role in this? K.T.: You have to keep in mind that after Wall Street’s Black Monday in 1929, the world’s economy had declined sharply. Due to the terrible recession, Japan’s unemployment rate was very high in the 1930s, and everyone wanted things to improve quickly. Until the early ’20s, many people had moved abroad. However, Japanese immigration to the U.S. effectively ended in 1924 when Congress passed the Immigration Act, which banned all but a few token Japanese people. Next, Japanese migrants turned to Latin America, and many moved to Mexico, Brazil and Peru, but the deteriorating political situation around the world made even this increasingly difficult. In the end, only Manchuria was left. That is why so many Japanese in the 1940s were eager to go to China.

What role did the Manchuria Railway Company (Mantetsu) play? K.T.: Mantetsu, far from being just a transportation company, was also involved in other aspects of the economic, cultural and political life in Manchuria. Among other things, it was responsible for power generation (coal, natural gas and oil) and transportation of primary products such as soybeans and wheat, and needed to train staff for its operations. It was also a powerful research institute and contributed to technological development in such fields as the chemical industry, agriculture and construction. In those days, it was also a general trading company and a general contractor. Last but not least, it acted as a huge advertising company. Indeed, you could say that the image of Manchukuo that people hold to this day was mostly shaped by Mantetsu in collaboration with military personnel and bureaucrats.

Judging from what you just said, I guess Mantetsu had a great influence on Japanese politics? K.T.: As I mentioned earlier, the political parties and the military in Japan shared the same interests, and Mantetsu became a sort of broker, connecting those two influential cliques. After the Manchurian Incident in 1931, the Cabinet led by the leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party, Wakatsuki Reijiro, resigned after failing to control the army and stop its advance into Manchuria. His successor, Inukai Tsuyoshi, was much closer to the military and caused a huge shift in the government’s stance toward China. The establishment of an authoritarian system through the close alliance between politicians and the military would lead to the collapse of democratic parliamentary politics.

Can we say that Mantetsu was instrumental in establishing Manchukuo? K.T.: It is true that when the entire Manchuria Railway came under the influence of the Japanese government and the Kwantung Army in 1937, the local administrative authority was no longer necessary, and control of the area along the railway line passed to Manchukuo. Even the teaching staff and engineers who worked at Mantetsu were transferred to the Manchukuo administration. This said, I think that both Mantetsu and the Kwantung Army played a role as leading national policy institutions in acquiring interests in the entire Manchuria region within the Japanese civil-military system.

Speaking of the Kwantung Army, what was its role in establishing Manchukuo? K.T.: The Kwantung Army was first established to defend the exclusive administrative area along the Manchuria Railway. However, after the Manchurian Incident, it became active over a wider area as multiple clashes with the Chinese Army called for increased military activities. It has to be said that the relationship between the Kwantung Army and the central authorities was not always good. In particular, it briefly engaged in a battle for hegemony with the Japanese Army but, in the end, it was taken over by the military authorities. In my opinion, the Kwantung Army should only be seen as the avant-garde of Japan’s expansionist drive in Asia and its empire-building efforts against China and Russia. It is simply that the postwar narrative tends to overestimate the role it played.

Manchukuo Propaganda Posters & Bills, Prof. Toshihiko Kishi’s Laboratory, Kyoto University

Is it possible to draw a parallel between the situation in Manchuria at that time and what is happening in Ukraine today? After all, Japan, like Russia today, was internationally isolated and subject to economic sanctions. K.T. : Did you know that Manchuria was once called the Asian Balkan Peninsula? This is because it was the central focus of the First Sino- Japanese War (1894-95), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), the Manchurian Incident (1931), the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), and the Soviet invasion just before the end of the Second World War. In that respect, of course, it is different from Ukraine today. However, it is true that there are some similarities between the two situations. For example, in 1933, two years after the Manchurian Incident, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations after the Lytton Commission concluded that it had wrongfully invaded Manchuria and that Manchurian territory should be returned to the Chinese. However, if you read the Lytton Report carefully, you can see that there was plenty of room for the Japanese government to compromise. It was Japan that decided to adopt a hardcore line. After that, Japan no longer had to comply with international rules, and the Sino-Japanese War broke out, though the Pacific War was not a direct consequence of the conflict in China. Russia is now on the same road to international isolation. The international community will continue to impose economic sanctions on Russia, but does not mean that Russia will immediately wage war on the Western nations. However, the situation may unfold in such a way that the post-Second-World-War world order could be restored. Only about 30 years have passed since the end of the Cold War, but there is a possibility that a new Iron Curtain may fall again between East and West.

Culturally, did Japan’s adventures in Manchuria influence Japan? K.T.: Especially during the Pacific War, Japanese culture could not thrive as state control and censorship became stricter. Under such circumstances, increasing numbers of creators and intellectuals tried to move to Manchuria and Shanghai to continue their artistic and cultural activities. In this respect, Manchuria was a kind of cultural sanctuary for those people; it was more tolerant than Japan since they could work relatively freely. The children of these immigrants grew up there in this atmosphere of freedom. It was these people who, upon returning to Japan after the war, had an impact on the national culture because they had not been affected by wartime censorship. They brought back those modernist tendencies that had blossomed in Japan in the 1920s, but had been repressed by the authorities in the ’30s and ’40s. As evidenced by recent historical research, this had a positive effect on every aspect of Japanese culture, from films, jazz and dance to painting, manga and literature.

In other words, the cultural influence of the Japanese experience in Manchuria was felt after, not before or during the war, right? K.T.: Exactly. The people who lived in Japan in those years were not free at all. Moreover, state control, censorship and the suppression of freedom of speech, which were already widespread in the late 1930s, became even stricter during the Pacific War. In that situation, it was not possible to engage in significant cultural activity. It is often said that Japan stopped laughing during those years.

What can you tell me about the philosophy of the “Five Races Under One Union”? Ethnically speaking, Manchukuo was a diverse state, but how did those races interact with each other? K.T.: It is true that several ethnic groups coexisted in Manchuria. The “five races” you refer to were the Manchus, the Han Chinese, the Mongols, the Koreans, and the Japanese. However, the term “Manchu” did not refer to the Manchu people but to the Han people who lived in Manchuria, so it was an ethnic group that overlapped with the Han people who lived in China. Also, sometimes there were posters that included White Russians in the “Five Races”, so the whole concept of “Five Races” was extremely vague. Moreover, even though the slogan “Five Races Under One Union” made it look like the five communities were equal and shared the same rights, the Japanese were in fact the ruling race. It was, in other words, a populist slogan that has nothing in common with the modern concept of multi-ethnic symbiosis.

Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Japan’s presence in Manchuria is often associated with such things as Unit 731 and widespread military cruelty. Do you think enough has been done in Japan to preserve the memory of these topics? If not, what should be done? K.T.: The problem with Unit 731 and the Nanjing Massacre is that they are highly politicised subjects, and it is not easy to clarify what actually happened, let alone remember it appropriately. Personally, I believe that we should not focus on these two issues when assessing the damage caused by the war in mainland China. The effects of the war, including the bombing of Chongqing, were more widespread, and the number of victims was even greater. I think it’s necessary to focus on the general idea of war and the disasters that accompany it as a whole, rather than on the alternative interpretations made by the perpetrators or the victims. We have to avoid the idea that some wars are just and others unjust. I do not think that kind of approach will lead to progress. As I said at the very beginning, the younger generations are no longer interested in the war itself, so we need to tell them about the damage, the sadness and suffering caused by war. I find that pop culture is a good vehicle to express those things. Films, TV shows, manga and games are very popular, particularly among the younger generations, and films such as “Grave of the Fireflies” and “In This Corner of the World” have touched the hearts of many people. We’re now living in the digital age, and in order to get the young more interested in these topics, we need to engage them through digital media. Also, I think that the process of handing down memories and the activities aimed at transmitting these values, such as organising meetings and talks with older people who directly experienced those things, as currently happens in many museums, is wonderful. The important thing is finding communication tools that are able to reach the target audience.

You published the “20th Century Manchurian History Encyclopaedia” about 10 years ago. Has there been any change in the way this episode of Japanese history is treated since then? K.T.: The intention of our editorial group was not to specialise only in Manchukuo but to address the problems that occurred in the Manchurian region within the framework of 20th-century history, the events that preceded the establishment of Manchukuo, and its eventual collapse. We aimed to approach the subject from multiple angles in order to achieve a more complex understanding from the point of view of both the occupiers and the occupied while connecting those events to later historical developments. Another thing we wanted to do with our work was to get away from the idea of confining the Manchurian problem only to the history of Japan. In other words, it seems strange to limit the history of Manchukuo to the relationship between Japan and Manchuria. This region, after all, is part of China. It is also on the border with the Soviet Union. Therefore, one thing we wanted to do was to relate its history to the larger relationship between all the nations surrounding it. Only in this way can you truly understand what Manchukuo was all about. It seems that our intentions were better understood in Taiwan and South Korea, maybe because those countries have experienced similar authoritarian regimes. The Manchurian Society of Korea even reviewed our encyclopaedia. However, in Japan, I don’t think that our approach has been understood. Too many people want to see Manchukuo as a “super ultra-country” and find it unacceptable to connect its history to that of socialist China. It is ideologically unacceptable to those on both the left and right. In that respect, thinking about Manchuria in the 20th century is quite difficult, to be honest, and this mentality has not changed very much.

How do young Japanese historians approach this subject? K.T.: They are very interested in individual themes, such as Manchurian literature or music for example. They really like the history of manga artists who were born in Manchuria. However, you should always keep an eye on the bigger picture, otherwise you are going to mistake individual parts for the whole. That is my opinion, at least, but these youngsters don’t seem to agree with me. They are always busy researching narrow, specific aspects of Manchurian history, but the way I see it, no matter how many individual themes you study you will never have a complete picture. I still think that the attempt we made with our encyclopaedia was very important, and even today it offers a valid point of view when thinking about what Manchuria really was. Whatever other people may think (laughs).

Interview by Gianni Simone