The cultivation of this flower took off in the Heian period (794-1185) after being imported from China.

From September onwards, the symbolic flower of the Imperial House is the focus of numerous festivities.

Which flower first springs to mind when you think of Japan? If you answer “cherry blossom”, most Japanese would agree with you. While Japan doesn’t have an official national flower, it is the sakura that captures popular imagination. Nevertheless, the country’s official symbol is the chrysanthemum.

The 16-petal chrysanthemum design appears on the Imperial Seal. It is seen on the cover of Japanese passports, on 50-yen coins and above the doors of Japanese embassies overseas. It is even engraved on the lid of the box containing the Japanese Constitution. The western term “Chrysanthemum Throne” is used to denote both the emperor’s throne and the imperial institution.

“The chrysanthemum symbolises the nation,” says Awane Maiko, deputy director of Hiroshima Prefectural Government’s Tokyo Office. “It has a particularly noble image, and it is the official emblem of the Imperial Family.”

And while the arrival of the chrysanthemum season doesn’t trigger the mass hanami viewing parties associated with cherry blossom, visitors to Japan in October and November can’t fail to notice the dazzling displays of chrysanthemums that spring up all over the country, sometimes in the most unlikely of places.

On the platform of a rural train station, for instance, you may find a dozen bonsai chrysanthemums and a host of full size blooms. A more modest arrangement adorns the entrance to the fish shop on the corner of our street. From the doorways of banks and schools to the window of the local baker’s shop, from hotel lobbies to sub post offices, chrysanthemums are everywhere, standing tall and straight like sentries. Even a public toilet may display a couple of blooms in a vase, which no one would dream of stealing or vandalising. Small wonder that autumn used to be called the “chrysanthemum months”.

Sakura and chrysanthemums are complementary opposites. The Japanese love cherry blossom because it captures the fragile, fleeting beauty of the ephemeral moment. Chrysanthemums, on the other hand, represent strength and long life.

Yellow chrysanthemums were cultivated in China way back in the 10th century B.C. During the Tang dynasty (618-907), white and purple chrysanthemums were also grown. In Japan, cultivation took off in the Heian period (794-1185), after first being imported in the Nara period (710-794). Today, Japan grows over 1,500 species.

Chrysanthemums were originally grown for medicinal purposes. The flowers are said to cure all manner of ailments, from fevers to inflammation and even heart problems, as well as imparting strength and vitality. They came to be associated with long life and good fortune.

Emperor Go-Toba (1180-1239) adopted it as the imperial symbol.

Sei Shonagon, the lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court who wrote The Pillow Book at the end of the 10th century, included the chrysanthemum on her list of favourite flowering plants. This suggests that it had become popular not just for its health benefits but for its beauty too. Emperor Go-Toba (1180-1239) is credited with making it the imperial symbol when he chose it as his personal emblem, decorating his sword, furniture, possessions and the Imperial Seal with chrysanthemum designs.

Unlike the sakura, the flowers even have their own festival day (September 9th), which is Chrysanthemum Day, also known as the Festival of Happiness. This festival dates back to the year 910, when the first chrysanthemum show was held in the Imperial Court. Sei Shonagon comments that the emperor’s palace was hung with chrysanthemum flowers for the kiku no sekku (Chrysanthemum Festival), and that they were left hanging there till the following May for one of the five traditional seasonal festivals. At Chrysanthemum Festival time, the Emperor offered his courtiers ritual sake with chrysanthemum flowers floating in it, to promote good health and long life.

According to Chinese yin yang philosophy, September 9th is the most important of the five seasonal festivals held to ward off evil. Days with multiple odd numbers were considered unlucky, none more so than September 9th because it contains a double nine, which is the largest single number. So purification rituals were performed at this time, including the use of chrysanthemum flowers.

Nowadays, on September 9th, many of these 1,000 year old rituals for long life are still performed at shrines and temples. Indeed, since the outbreak of the pandemic, the chrysanthemum flower’s power has acquired new relevance.

Noh performances are held, portraying age old stories like that of the Chrysanthemum Boy. This mythical youth was a favourite of the emperor, but was banished to a remote mountain for a misdemeanour. Taking pity on the boy, the emperor gave him a sacred Buddhist scripture. The boy memorised it by copying it onto chrysanthemum leaves. He then drank the dew collected on the leaves, and thus became immortal.

This story is reflected in the popular tradition of covering chrysanthemum flowers in silk floss or cotton wadding overnight, then wiping your body with the accumulated dew the next morning, to protect you from the ills of old age. This ritual is still performed at some shrines.

In Hiroshima, the Chrysanthemum Festival, or Choyosai, is held at Gokoku Shrine, the city’s biggest Shinto shrine, on the nearest Saturday to September 9th. After a ritual prayer for good luck, there follows a performance of kagura a stunning dance and music spectacle featuring handsome heroes, evil dragons and head spinning sword fights, originally designed to please the gods.

“Kikuzake is served during the festival,” explains Ikeda Reina, Hiroshima resident and miko (shrine maiden). “This is sacred sake in which chrysanthemum flowers have been soaked overnight. In Japan, it’s said that the chrysanthemum is good for a long life, so people drink kikuzake and wish for good health.” In addition to the Chrysanthemum Day rituals on September 9th, you can also see exhibitions of chrysanthemums nationwide in October and November, when they are in full bloom. “The variety of chrysanthemums is constantly being improved, and there are many different types,” says Maiko. “So, chrysanthemum exhibitions are held all over the country to compete for the most beautiful variety.”

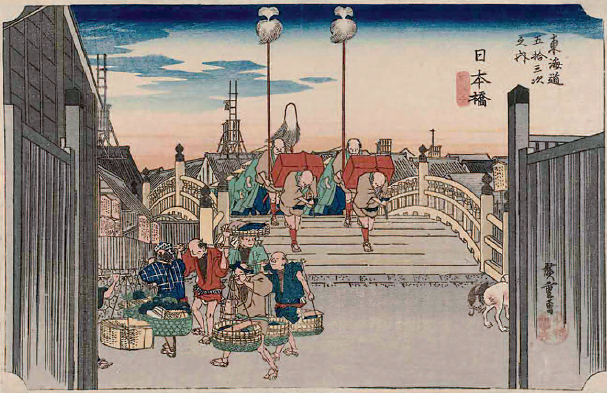

These exhibitions are spectacular events. Typical displays include bonsai chrysanthemums, cascading chrysanthemums, and life-size human dolls dressed in costumes made of chrysanthemums. Also popular are miniature models of local landmarks like temples, pagodas or bridges, decorated with a mass of brilliant blooms.

One such event is the Kiku Matsuri, held every November at Tokyo’s Yushima Tenmangu Shrine. Some 60 members of the local group of chrysanthemum enthusiasts take part, and even local elementary and junior high school students participate. The event draws over 100,000 visitors every year.

But you don’t have to visit the capital to see these autumn blooms at their gorgeous best. In Hiroshima, for example, two annual exhibitions are held. One takes place at Shukkeien Garden, a “shrunken scenery garden” built in 1620 and modelled on the landscape around Lake Xihu in China. The garden’s koi ponds, tea houses and shady groves provide an idyllic setting in which to view the chrysanthemums. Coach loads of visitors come from all over Japan, not just for the flowers but also for the Chrysanthemum Tea Ceremony.

Another event takes place in the grounds of Hiroshima Castle, where over 2,000 pots of chrysanthemums are exhibited. The Mayor’s Prize is awarded for the best of the larger displays. Here, along with a profusion of bonsai, cascading chrysanthemums, large flowered chrysanthemums and chrysanthemum balls, you’re likely to find chrysanthemum decorated models of local beauty spots like Miyajima Island, or larger than life koi carp, a cherished symbol of the city. The heady fragrance of this splendid profusion of flowers, together with the gentle sound of koto music from a nearby stage, make this event a delight for the senses.

Sadly, many such events – such as Gokoku Shrine’s Choyosai – have been cancelled over the last two years because of the pandemic. Yet if you are in Japan this autumn, you’ll still be able to see legions of chrysanthemums standing tall and proud as usual, brightening the streets with explosions of colour. They are a living symbol of Japan’s strength and resilience. And that’s something that will endure long after this pandemic is over.

Steve John Powell & Angeles Marin Cabello