In the space of a few decades, animation has become a mainstay in the world of Japanese pop culture.

An essential element of Japanese pop culture, animation has a long history. Here it is.

For many people outside Japan, watching anime is their first contact with otaku culture and remains their main interest. Anime as we know it today is a post-Second World War phenomenon, but the first attempts at producing animation in Japan go all the way back to the beginning of the last century, when people tried to make their own versions of the popular Disney cartoons. The first major work to win international praise was OFUJI Noburo’s The Thief of Baguda Castle, made by using Japanese coloured paper in a cut-and-paste technique. One interesting feature of Japanese animation today is the sense of intellectual freedom and ideological independence shared by many artists and best exemplified by Studio Ghibli’s MIYAZAKI Hayao’s pacifism and anti-government attitude.

Yet early supporters of the anime industry included public institutions that commissioned works for PR campaigns. Then it was the increasingly authoritarian government that enrolled animators to back its nationalistic policies. The first Japanese feature-length work (SEO Mitsuyo’s Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors, 1945) was actually a Navy Ministry’s propaganda film featuring a puppy, a monkey and other animals in typical Disney style.

The American company played another important if indirect role in the birth of postwar animation when the president of Toei (one of Japan’s major film companies) saw Snow White and, in 1956, was inspired to create Toei Doga (today’s Toei Animation, the studio where both anime giants MIYAZAKI and TAKAHATA Isao began their careers). To this end, he sent a research team to America and invited several foreign experts to create a modern animation studio.

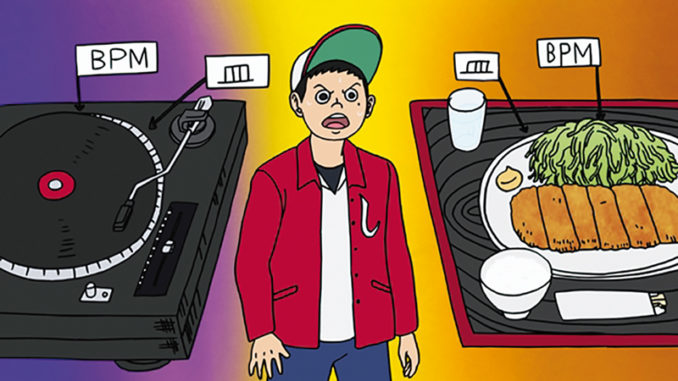

The first decade of the modern era was rife with problems, including financial and labour struggles, but things finally gained momentum in 1963 when TEZUKA Osamu’s Tetsuwan Atomu first appeared on TV starting a huge anime boom. Astro Boy – as it is better known in the West – also created a blueprint for future TV anime production as the studios, in order to make animation cheaply and quickly (to meet deadlines), began to cut the number of drawings (and lines) in each image and to alternate animated scenes with still images, while cleverly using sound effects, dialogue and other ways to simulate movement.

The decade between 1963 and 1973 is usually considered the golden age of classic anime, when TV shows were very much part of primetime programming, and watching cartoons was a regular activity for many Japanese families. Atom used to air weekday evenings, and by 1979, there were 18 prime time anime series, with multiple shows competing against each other in the same time slots on different networks. Throughout that decade, anime remained a form of children’s entertainment, mainly focusing on humour, family drama, sports, science fiction, and girls with magical powers. In 1969, for instance, popular manga Sazae-san became a TV show, and today it’s the longest-running anime in the history of TV. But in 1974, Space Battleship Yamato changed the rules of the game by introducing complex adult-oriented themes and ideas, and becoming in the process a social phenomenon that later influenced such cult shows as Mobile Suit Gundamand Neon Genesis Evangelion. The latter series, in particular, did well as late-night reruns, leading to more shows being created specifically for after-midnight programming, where they could feature more mature content.

In Japan the term “anime” covers worldwide animation, while abroad it has become synonymous exclusively with works from Japan in recognition of the uniqueness and originality of Japanese animation. Similar to manga, Japanese anime has complex storylines exploring an extremely wide range of subjects, from the familiar to the eccentric (e.g. the surreal combination of cute girls, weapons and warfare in Kantai Collection and Girls und Panzer), and including some (e.g. pornography, violence) that very few Western studios would dare to touch. Likewise, anime characters often have fully developed personalities and openly convey their feelings through subtle body language, exaggerated visual effects, and highly expressive eyes, in a way that goes well beyond Western animation’s limited range of facial expressions and heavy use of dialogue.

Since the early 1990s, though Japanese studios have kept churning out new series and feature length movies, the industry as a whole has suffered a slump partly due to a shrinking fan base at home and competition from new forms of entertainment such as mobile phones. With a falling birthrate, series for families with young children have inevitably attracted fewer viewers. Also, technological developments in recent years mean that more viewers now consume anime without relying on traditional broadcast television at all.

As a consequence, TV anime such as Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan, which in the past achieved reliably high ratings, have disappeared from TV screens during prime time.

for most people involved, working in anime production remains a labour-intensive and poorly paid job (according to veteran animator kAMIMuRA Sachiko, newbies earn on average about 100 yen an hour – less than £1). even Evangelion creator ANNO Hideaki has stated that, in the not so distant future, Japan’s lack of money and animators may lead to the local industry being outdone by up-and-coming Asian countries like South korea and Taiwan. however, judging by the steady stream of new titles coming out of local studios, the overall picture does not seem so bleak. After all, there are still a remarkable 622 anime-related companies in Japan (542 of them based in Tokyo), whose work ranges from planning, production and script writing to drawing, special effects, shooting and editing.

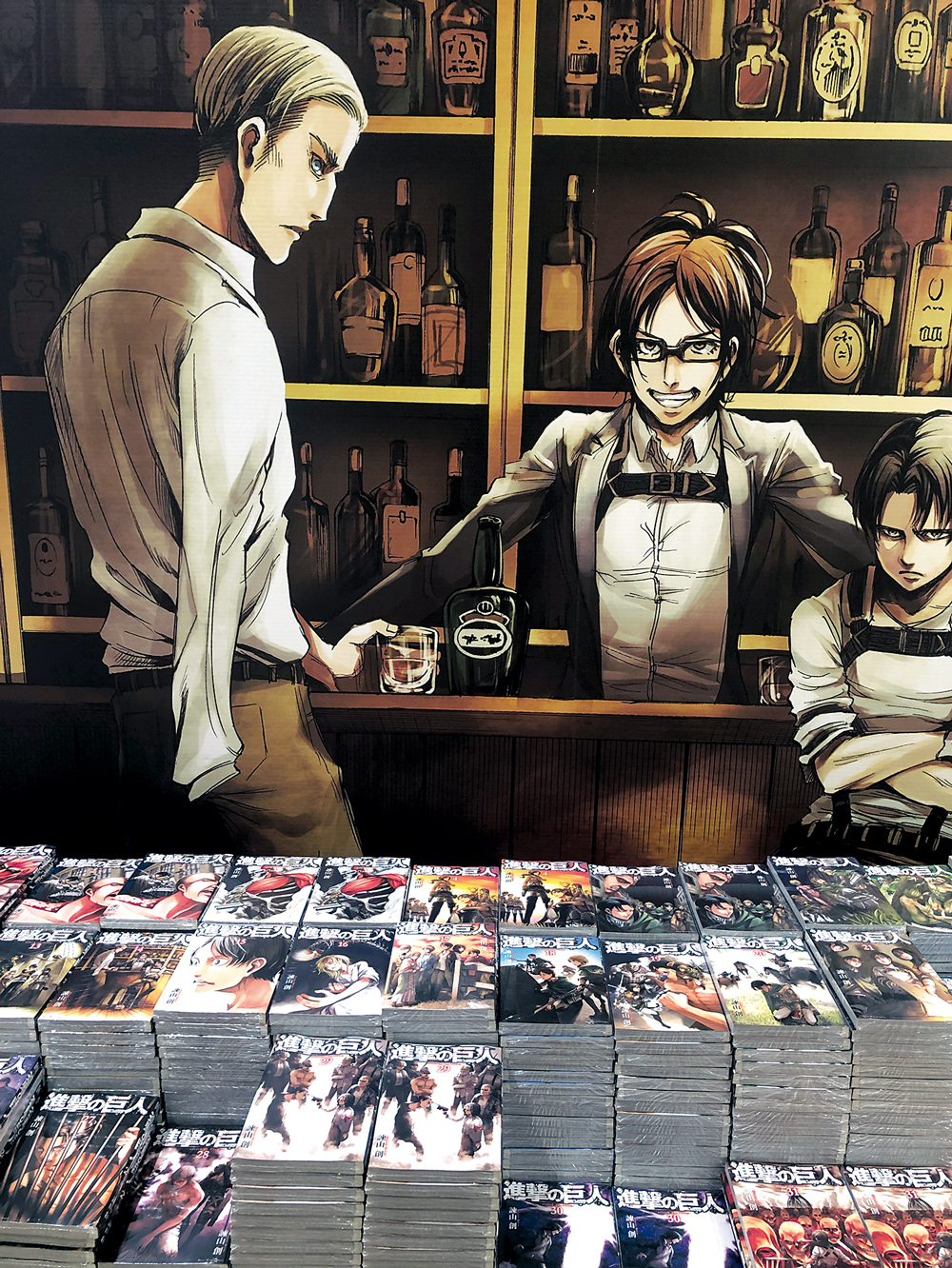

even without considering recent international mega-hits such as Your Name and Demon Slayer, animated feature films dominate the local box office every year, especially during the spring and summer school holidays when the usual suspects (Detective Conan, One Piece, Doraemon, Pokemon) appear. In 2019 for instance, five of the 11 top-grossing titles in local cinemas were either feature-length animation or live-action versions of popular manga and anime – a feat no other country can hope to emulate. The small screen is no different as TV programming still features many anime series, from family-friendly evergreens (Anpanman, Crayon Shin-chan, Chibi Maruko-chan, Sazae-san) to works with more complex and adult-oriented themes (or particularly violent scenes), which are broadcast after midnight (e.g. Demon Slayer). In 2018 the Japanese animation market recorded its ninth consecutive year of growth, though there was a slowdown in overseas sales (101.4% compared to 178.7% in 2015, 131.6% in 2016 and 129.6% in 2017).

In the future, we can expect to see more anime series aimed at older audiences (due to the lack of young viewers in Japan) and even more series made with the international market in mind.

JEAN DEROME