In Shibuya district, Tokyo, a couple search for a love hotel.

In Shibuya district, Tokyo, a couple search for a love hotel.

In Dogenzaka district alone there are some 300 love hotels. A unique Japanese feature that is worth a visit.

Dogenzaka Hill in Shibuya is one of those places that never sleeps. Art Theatre Eurospace screens films late and Club Asia is a hotspot of the local nightclubbing scene. However, most of the people who roam Dogenzaka’s maze of narrow streets are here for another reason: to spend a few hours or the night in one of its 300 love hotels.

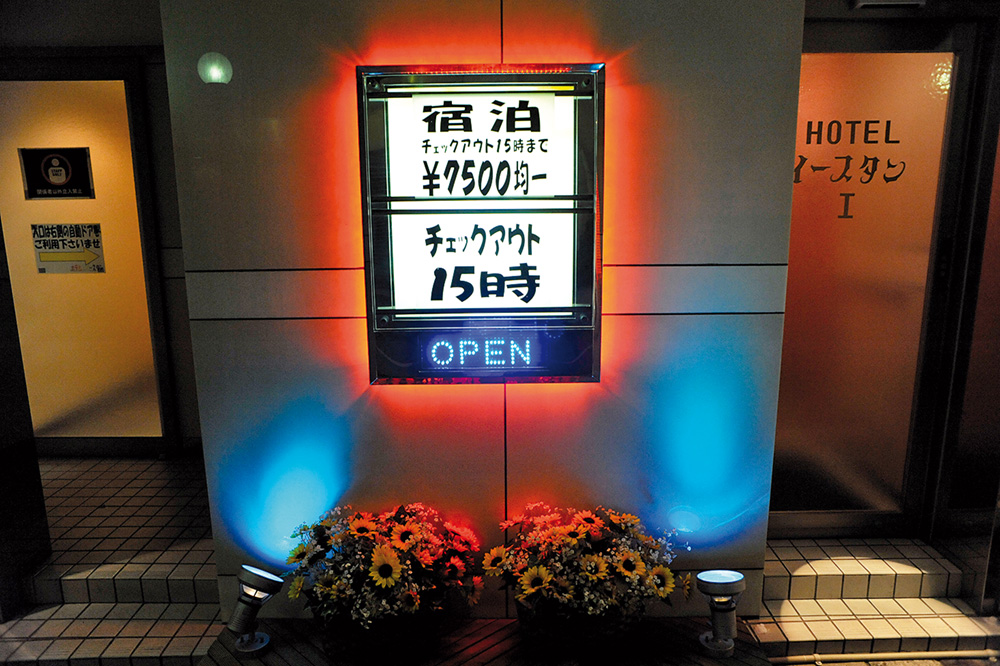

Take, for example, Hotel AREAS. At first sight, you could mistake its dull white façade for that of a business hotel. Then you notice the two separate doors – one for entering the building and one for leaving – and the sign advertising “rest” and “stay” fees – “rest” being a visit of two or three hours in the morning or afternoon, while “stay” means an overnight stay at full price. These are tell-tale signs that sleeping is the last thing on the guests’ minds.

The new generation of love hotels is a far cry from the flashy, gaudy establishments of old. One of AREA’s neighbours, for instance, used to have a bright-red façade and stucco columns that made it look like a cross between a Chinese restaurant and a Greek temple. Alas, that hotel, like many others, has recently been torn down and replaced by a less ostentatious building.

In an effort to clean up their act and become more respectable, many establishments have even changed name. Indeed, the whole category now prefers to be labelled as either leisure or boutique hotels. However, most people still continue to call them rabuho (short for love hotel).

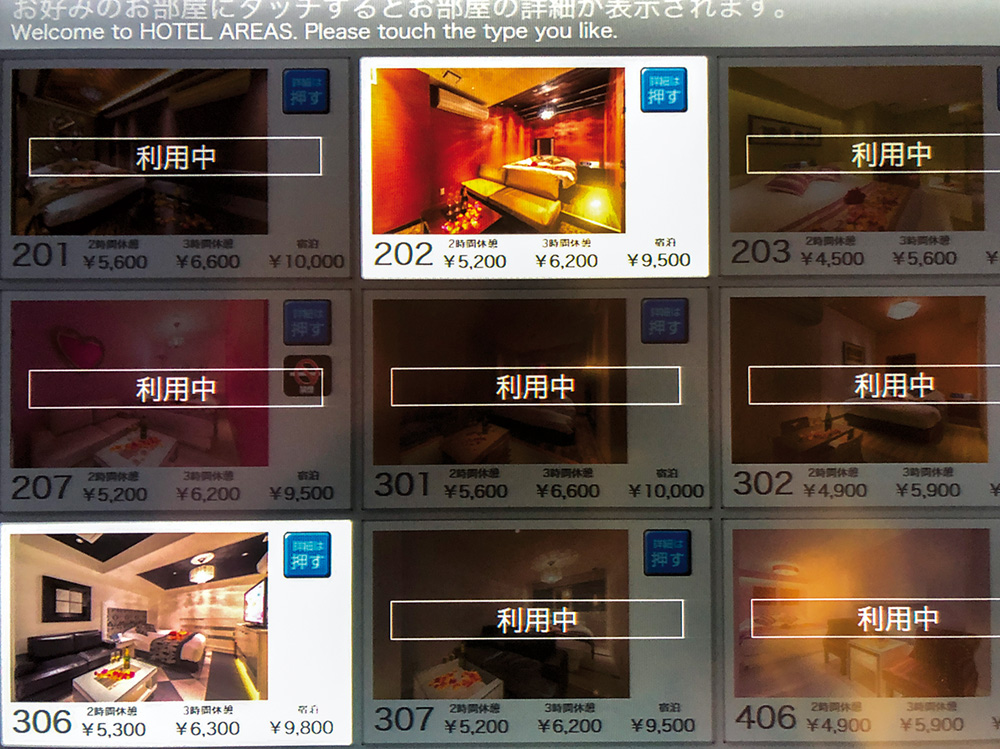

Back to AREAS to have a look inside. A pink corridor leads us to a big touch-screen display with pictures of the various rooms and their prices. Rooms that are lit up are still available. Once we’ve made our choice, we pay at a small window and get the room key from a middle-aged lady who reminds us that no more than two people are allowed in the room. We can only see her hands because love hotels are all about privacy and they go out of their way to avoid eye contact. Sunday afternoon is a popular time to visit a love hotel. Many rooms are occupied and we bump into another couple as we get out of the lift. The room is rather small – smaller than the wide-angle photo advertising it downstairs, has no window (again, to allow for privacy) but a large bathtub, a red sofa and a heart-shaped mirror. The largescreen television has lots of porn channels, but there are no sex toys in sight and only two free condoms.

This is how a mid-priced no-frills room looks like today. However, as I mentioned earlier, love hotels have a long history, and have passed through several permutations, and there was a time when many of them were garishly designed sex theme parks. But how did they end up looking like this?

“Love spaces” that could be rented by the hour date back to the deai chaya (lit. meet-up tea houses) of the Edo period (1603-1867), which were rather closer to brothels as they were mostly used by geisha or courtesans and their clients. Ordinary unmarried couples and adulterers had to settle for the great outdoors, whether a park, riverbank or the grounds of a shrine.

It was only in the 1930s that the forefather of the love hotel appeared. Japan, like many other countries, was hit hard by the Great Depression, and many businesses had to lower the prices of their goods and services. Someone eventually came up with the so-called enshuku (lit. one-yen dwellings) that ordinary couples could rent cheaply for a few hours rather than paying more for a whole night. Apparently, one of the enshuku’s main selling points was that doors could be locked, thus offering an unprecedented level of privacy. The lock on the door is one of many innovations that throughout their long history have placed love hotels at the forefront of the hospitality industry. Many enshuku either had to close down or were bombed during World War II, pushing people outdoors again (the park in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo and the area around Osaka Castle were said to teem with amorous couples), but the postwar reconstruction led to the rise of tsurekomi yado (lit.bring-along inns) whose great attraction was private bathing facilities – a great luxury at a time when most homes did not have a bath and people frequented public baths instead. The tsurekomi yado proved so popular among professional sex workers, married couples in search of privacy and assorted lovers that by 1961, there were 2,700 such establishments in central Tokyo alone.

At AREAS love hotel in Dogenzaka, you choose your room on a touch screen.

At AREAS love hotel in Dogenzaka, you choose your room on a touch screen.

Love hotels took on their classic form in the 1960s, but in those years they were called moteru or motels, were mainly located outside the large city centres (the first one opened in 1963 in Ishikawa Prefecture) and were frequented by the growing number of people who owned a car. Among the innovations introduced into these motels were television sets and air conditioning. Also, the two-storey buildings had a garage on the first floor which provided anonymous access to the rooms above.

The word “love hotel” finally came about in the early 1970s. It’s said to have originated in Osaka when patrons of the Hotel Love began to reverse its name. The 1970s were also the beginning of the golden age of love hotels. It was in those years that a growing number of establishments opened in the cities and Western-style rooms slowly began to replace tatami floors and futons.

The coming of a new era was announced by the arrival, in 1973, of two new establishments – both located in Tokyo – that instantly grabbed the front pages and people’s imagination. First, popular singer SATSUKIMidori opened Hotel Japan, a luxurious affair with “Italian style” interiors where, according to SATSUKI’s words, “the dreams of young lovers will come true”. However, the singer’s love nest was soon overshadowed by a castle-shaped building that would go on to become the most famous love hotel of all time: the Meguro Emperor.

Inspired by Cinderella’s Castle at Disneyland (an attention grabber during a time when love hotels could not be openly advertised in the media), the Emperor was outrageously expensive, but people flocked to its 30 rooms to experience the ultimate in luxury service, helping the hotel achieve a monthly turnover of 40 million yen.

The huge success of Hotel Japan and the Meguro Emperor pushed many other love hotels to go down the deluxe route, where “deluxe” often meant coming up with the most outrageous ideas. Designers’ imagination and available budget were the only limits to what could be achieved. Soon, scores of hotels had rooms that looked like pirate ships, Playboy grottos, space ships, SM dungeons or even a boxing arena with a ring-shaped bed in the middle. On top of that, every establishment tried to outdo its rivals by installing revolving or vibrating beds, planetariums, gondolas, swings, aquariums with glow-in-the-dark jellyfish, featuring Disney or Hello Kitty memorabilia or blacklight artwork. And lots and lots of mirrors everywhere – all in the name of escapism and the ultimate kinky experience. Western observers may have derided them as kitsch and tasteless, but the Japanese invariably regarded them as beautiful and romantic. After all, it’s not by chance that Tokyo Disneyland, which opened in 1983, is the world’s third-most visited theme park.

At the time, though love hotels, just like normal hotels, were regulated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, they were seen as places of dubious reputation, and their media coverage was limited to late-night TV programmes and sex magazines. So in 1984, the government put them under the jurisdiction of the New Public Morals Act together with such sex-related businesses as soaplands and strip clubs.

At the same time, their patrons – particularly the women who were becoming more vocal when it came to choosing a hotel – began to ask for something different: cheaper rooms and simpler designs with more amenities – things like karaoke equipment, game consoles, and other types of entertainment. In other words, love hotels began to be seen as places where couples not only went to have sex but to spend a few hours or the whole day relaxing and having fun.

One door to go in and another to leave, everything to maintain a client’s privacy is provided.

One door to go in and another to leave, everything to maintain a client’s privacy is provided.

The industry’s answer to this new challenge (and a new stricter change in the law in 2010) was to reinvent the love hotels and transform them into “leisure hotels” – a sort of improved version of spartan business hotels with modern, stylish interiors and a wide selection of conventional amenities including massage chairs, jacuzzis, and access to dozens of music channels. Also, as a further nod to women’s buying power, hotel managers swapped whips and chains for the latest herbal shampoos and conditioners. Even today, they are more likely to attend the annual Leisure Hotel Fair in Tokyo (that last year attracted 11,000 people and 156 companies) than a sex toy convention.

These days, a growing number of establishments go so far as to offer special, low-priced deals for single women who want to spend the night at a hotel. These “plans for ladies” offer female guests a resort-like experience featuring beauty care and gourmet meals. Even the old Meguro Emperor, after falling on hard times in the 1990s, was recently renovated and now offers a Joshikai (Girls Party) Plan where women can check-in after work and have fun in rooms equipped with 110-inch projectors, 5.1 ch surround sound systems and “luxury beds used in the world-famous Ritz-Carlton and Westin hotels”.

In the cut-throat hospitality industry, where owners struggle to stay ahead of the game, any guest is welcome. Today’s love hotel customers range from young couples in their 20s to curious foreigners, and from businessmen with prostitutes to older couples looking to spice up their marriage while getting away from their kids. To help adulterers with their escapades, there’s even a special music channel called “alibi” – a throwback to the old iiwake terehon (excuse phone) – that broadcasts background noises such as car traffic or a pachinko parlour, in case they have to call home. The only customers who are still largely unwelcome are same-sex couples. Unfortunately, most love hotels keep ignoring a 2018 revision to the hotel business law which states that it is illegal to reject guests based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The ban on the gay community is hard to explain, especially considering that business is not as good as it was. At the turn of the century, for instance, there were an estimated 30,000 love hotels in Japan, but now their number has dwindled to fewer than 6,000. However, they still welcome around 1.4 million people every day, and analysts believe the industry generates between two and three trillion yen annually.

So long live the love hotels. After all, they are – according to some people – Japan’s greatest invention of all time.

JEAN DEROME

Eric Rechsteiner helped

in researching this story.