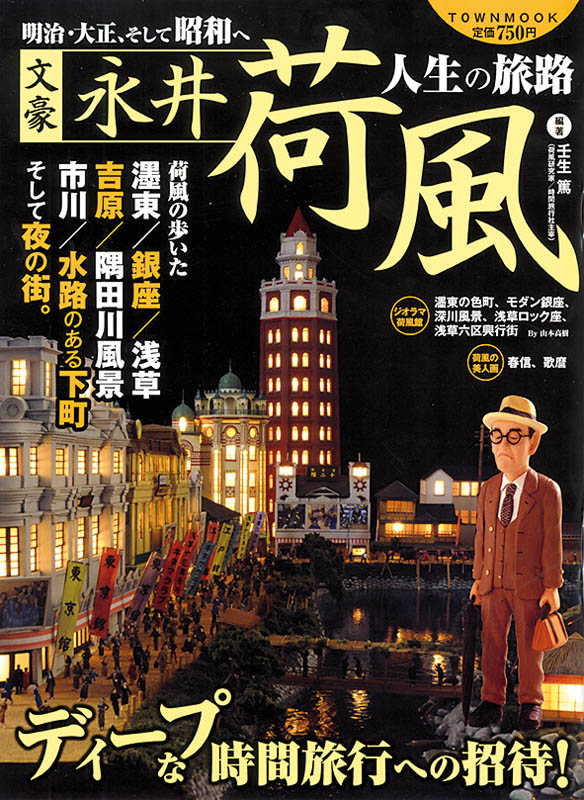

Mibu Atsushi’s extensive knowledge allowed us to plunge into the world of this lover of Tokyo.

Forget Murakami Haruki and other contemporary enfants prodiges. When the Japanese talk about Tokyo and books, one name is mentioned before any other: Nagai Kafu. Last year it was the 140th anniversary of his birth and the 60th of his death, but ZOOM preferred to wait until now, the annus terribilis of coronavirus and the troubled Tokyo Olympic Games, to celebrate the life and work of an author who is still relatively, and undeservedly, little known in the West, but who in his own country is considered literary royalty.

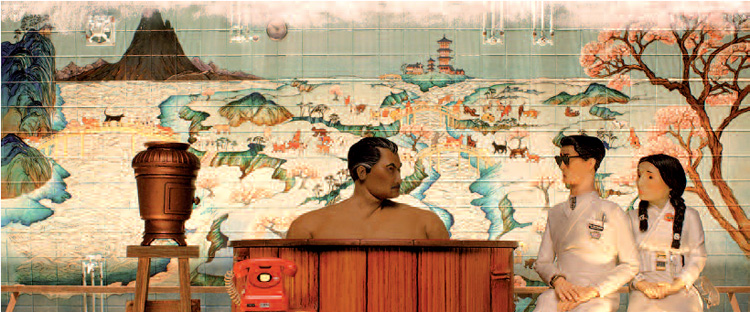

Most of Kafu’s work is intimately related to Tokyo, the city where he was born in 1879 and spent most of his life, so much so that at times the metropolis itself seems to be the real protagonist of his novels and short stories. Often mixing autobiographical elements with a strong nostalgia for the culture, social mores and styles of the 19th century, Kafu returned again and again to the demimonde of geishas and the sex trade that he had eagerly immersed himself in since his teenage years. One such example is A Strange Tale from East of the River, a short novel that he originally self-published in April 1937 before it was serialized, first in the Asashi newspaper and then published by Iwanami Shoten later that year.

In order to understand better the author’s love affair with Tokyo, I meet one of Japan’s major experts in all things Kafu, Mibu Atsushi, a writer, editor and self-styled “time traveller”. We arrange to meet in Higashi-Mukojima, the place where the main action in A Strange Tale takes place.

Both the station (first opened in 1902) and the surrounding district used to be called Tamanoi, but in 1988, Tobu Railway decided to change it to Higashi-Mukojima. “Actually, the locals wanted to keep the old name, and at first protested vehemently against the change,” Mibu says, “but eventually they met with Tobu representatives, and the railway company was able to convince them over some food and booze (laughs). It couldn’t have been much of a protest.”

Leaving the station, we head north following in the writer’s footsteps. “Kafu was famous for approaching his storytelling like an explorer/cartographer,” Mibu says. “He often took pictures, drew sketches and even maps of the locations he chose for his stories. According to Kafu’s diary – later published as Danchotei Nichijo – he first visited Tamanoi in March 1936, his main goal being the local red-light district. On 22 April, he wrote the essay ‘Terajima Diary’, which details some of his discoveries and notes on the area. On 7 September, he recorded the first meeting with a woman who is said to be the inspiration for the novel’s female character, Oyuki. It took him only one month to write the novel, from 20 September to 25 October.”

The first intersection we reach is Taisho-dori (Taisho Street) that was originally built around 1913. “This is the direction from which Kafu arrived in 1936 when he first visited the district and wrote the essay ‘Terajima Diary’,” Mibu points out. “Both Kafu and Ooe, the novel’s protagonist, come from Asakusa by bus.”

When it comes to Japanese cities, 80 years are like 80 centuries, which means that nothing remains of Kafu’s Tokyo. Nowadays, one is lucky to still find any buildings from the 1950s and ‘60s. “The interesting thing about Tokyo,” Mibu says, “is that old buildings may give way to new ones, altering the whole atmosphere, but the street plan never changes. For example, if you compare this area’s current map with one from the 1930s, when A Strange Tale was written, or even before the 1923 Great Tokyo Earthquake, the streets are just the same.” To prove his point, Mibu shows me a photo that Kafu took back in 1936 during one of his explorations. In fact, even utility poles are exactly in the same spot. Featured in the same picture are the long-gone Mukojima Theatre and a Tobu train coming in from the left – at the time the Isesaki Line was still running at street level. “Kafu waited a long time to get a nice photo of the train,” Mibu says, “but when it finally appeared, a group of people on bicycles stopped in front of the level crossing, ruining the image. Apparently, this upset him a lot.”

On the right side of the railway, Taisho-dori becomes Tamanoi Iroha-dori. We now enter the novel’s main location. “For some reason, the area to the left of Iroha-dori miraculously survived the 1945 air raids,” Mibu says, “while the one of the right was completely destroyed. In other words, Iroha-dori acted as a sort of firebreak, preventing the whole district from burning down. After the war, many of the businesses that used to be located on the right side moved to the left.”

However, A Strange Tale was written before the war, so we enter the thick cluster of two-story houses on the right side of the street. It’s here that the old akasen (red-light district) was located. “However, in the Meiji and Taisho periods (1868-1912) people didn’t use that term,” Mibu says. “Instead, brothels were called meishaya because they were thinly disguised as shops selling alcohol. The Tamanoi brothels were originally located in Asakusa, but they all moved east of the Sumida River between 1918 and 1923, the year of the Great Kanto Earthquake.”

We soon find ourselves in a maze of narrow alleys, which in Kafu’s time twisted their way along a presumably smelly ditch. Nowadays, the water flows underground, but Mibu can still point out the exact spot where Oyuki’s house stood. At this point, he produces a copy of the novel out of his pocket and starts reading the passage where Oyuki leads Ooe to her home: “We turned down a winding alley, and at every turn she looked back to make sure I was still behind her. Eventually, we crossed a little bridge and found ourselves in front of a strip of low buildings with signs and awnings”. The narrator is painfully aware that “even this backwater town, was not able to escape the manic upheaval of the times”, but the house where Oyuki lives “felt, to someone like me, left behind by the times, as if we were connected by a deep, mysterious fate”.

Getting out of the maze is a seemingly impossible task as each alley seems to end in a cul-de-sac, but in time we find a way out and with the help of our expert guide, we finally return to Iroha-dori.

Mibu shows me another photo taken by Kafu in 1936, featuring a torii, a stone pillar with the inscription Toseiji on it, and a pay phone. Then he points at a spot across the street. “That’s where they use to stand,” he says. Kafu’s photo is quite puzzling because the torii is a Shinto gate while Toseiji is a Buddhist temple. Mibu sees my confused expression and reads another excerpt from the book: “Just over the little bridge was a small intersection, where a shop selling horsemeat sat, a stone pillar indicating the entrance to a Zen temple, a torii for the Tamanoi Inari Shrine, and a pay phone”. It turns out that Toseiji and the Tamanoi Inari Shrine shared – and still share – the same location. “It’s interesting how faithfully, almost obsessively, Kafu included these real-life details in his stories,” Mibu says.” Most of them are gone, but at least one of them is still here.” I turn to my left and, lo and behold, there is still a butcher’s shop on the corner.

We cross Iroha-dori. Though the torii and pillar are gone, the temple/shrine can still be found at the end of the street – though nowadays it’s in the form of a grey three-storey modern building that blends perfectly into its surroundings except for a funny-looking logo like a ship’s wheel.

I came to Mukojima with the secret hope of finding at least a few old buildings, and, in this regard, I’m not disappointed because in the area to the left of Toseiji we soon discover several Showa-era houses – probably lucky survivors from the 1950s and ‘60s. They are easy to spot not only because they obviously look very old but because in contrast to the other houses – those bland-looking prefabs that can be found everywhere around Japan – they are made of mortar and corrugated iron and have other unique features such as coloured tiles, curved surfaces, and stained-glass windows with exquisitely carved wooden decorations. Mibu points out that prostitutes often used the second-floor balcony to call to prospective clients – which reminds me that the maids working at Maidreamin Café in Akihabara do just the same thing (I mean, calling out to the strolling otaku from a balcony).

At the end of our walk, we chat about Kafu’s relationship with Tokyo and Mukojima over a cup of tea. “The district where I grew up, now called Tachibana, is located on the east side of Sumida Ward, but it’s quite similar to Mukojima/Tamanoi.” Mibu says. “Also, as a child I visited Mukojima Hyakkaen, the famous garden located less than a 10-minute walk from here. I encountered Kafu much later, of course, but reading his work was like having déjà vu because in his stories and novels I found places I had already visited or seen in movies such as Where Chimneys are Seen. That’s why A Strange Tale strikes such a chord with me. It reminds me of my childhood and the place where I used to live and play when I was a child.”

Many literary commentators are puzzled by Kafu’s work and all too often find it hard to pinpoint his success as a writer. “He certainly wasn’t much of a storyteller,” Mibu says. “But he was particularly good at creating – or maybe recreating – a unique atmosphere; helping us experience the sights, sounds, and smells of a long-gone Tokyo. He also likes to play with readers’ expectations, making us guess who Oyuki might be and where the story is going. After all, even during his time it was well known that he often mixed fantasy and reality in his stories. For one thing, Ooe is clearly Kafu himself. And many other details are taken straight from his own life.

“Kafu wrote A Strange Tale when he was 58. Walking around Tamanoi reminded him of his youth, when he was in his 20s, and Asakusa (at the time Tokyo’s main entertainment area) and the red-light district of Yoshiwara were his main playgrounds. He began to explore the area east of the Sumida 13 years after the Great Kanto Earthquake had laid waste to central Tokyo. Post-earthquake reconstruction had irreparably changed his beloved city, and low-key, ‘dirty’ Tamanoi probably reminded him of that lost world. That’s why he was drawn to the unfashionable area east of the river. It’s a perfectly understandable attitude for it works even for me: I’m endlessly attracted to Mukojima because for me, walking these streets feels like embarking on a kind of time travel.”

The concept of furusato (hometown, birthplace) plays a central role in Japanese culture and people’s imagination. Tokyo, in particular, is a city of immigrants; people who were born in other regions and usually visit their families for Obon, the summer festival of the dead, or to celebrate the New Year. Sometimes they even move back to their hometown after they retire. “But for people like Kafu and me, things are slightly different,” Mibu says. “Tokyo is our birthplace, but this city changes at such a furious pace that our ‘hometown’ looks very different from even ten or twenty years ago. So if you want to find that old ‘hometown feeling’, you have to look for it somewhere else. In this sense, A Strange Tale, though set in a real place, may be considered as a sort of fantasy – a dream story.”

Mibu believes that Kafu would never approve of the way Tokyo has changed in the last 50 years. “Even during his time he was less than enthusiastic about progress,” he says. “Let’s compare the way he and Natsume Soseki, another literary giant, reacted to the Eiffel Tower. In 1900, Soseki, who was studying in England, visited France and climbed the world-famous iron tower. Then, in a letter to his wife he wrote at length about the futuristic lift system that had taken him to the observation deck, even forgetting to mention what he has seen from the top of the tower. Seven years later, the then 28-year-old Kafu left the United States where he had studied for almost four years, and visited France on his way back to Japan. Travelling by train from Le Havre to Paris, he saw the Eiffel Tower from a distance and wrote, ‘Under the white summer clouds, the Eiffel Tower suddenly appeared. A river peacefully flowed next to the tracks’. That river was the Seine, and it appears over and over again in his writings. However, the tower is only mentioned that one time.

“The same thing can be said about the 12-storey Ryounkaku. Built in 1890 and affectionately called Asakusa Junikai, Japan’s first-ever skyscraper was extremely popular with everybody but Kafu who found technology completely charmless. In fact, it’s barely mentioned in his work. So I’m pretty sure that he would be appalled by the Tokyo Skytree and all the other steel and concrete monsters that have appeared in Tokyo’s cityscape.

“It’s not by chance that in his later years, after the war, Kafu moved to Ichikawa, in nearby Chiba Prefecture. As he wrote in his diary, he had to move farther to the east to find a semblance of his beloved Tokyo of the past, surrounded by fields and flowers. Now, unfortunately, even from that distance he would see the Skytree!

“Toward the end of A Strange Tale, Ooe walks around the neighbourhood where Oyuki lives, and ruminates on his attraction for such a place: ‘I could not help the sentimental sigh that escaped me when I remembered that, once, Terajima was just rice fields, the small river filled with water grasses, small dragonflies perched delicately on their leaves’. ‘Time travellers’ like Kafu and me roam the outskirts of Tokyo in search of that elusive feeling. We derive an extraordinary pleasure whenever we find a pocket of our past in a backstreet or alley where cats slumber in the sun and people still live their life at a slower pace.”

Jean Derome