Since its first appearance in 1970, An An has always reflected the development of Japanese women as they have became stronger and more independent of men.

1970 marked the emergence of a new Japan where women started to play an increasingly important role.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, from which it emerged almost totally destroyed, Japan decided to embrace reconstruction in order to bring itself up, once again, to the same level as Western countries. Although it definitively renounced the use of weapons in pursuit of its goal, the journey it chose to undertake was never straightforward. Several key dates mark the transformation of the country, 80% of which had been razed to the ground by 1945. Each one of them illustrates another stage on the path to nirvana that Japan has aspired to since the end of the 19th century.

Without listing them all, there are two that stand out: 1964 and 1970. Their importance can be gauged by the fact that when, in 2008, the publisher De Agostini Japan published its historic series Showa Taimuzu [Showa Times] to assess the 64-year-long reign of Emperor Showa (Hirohito), the present sovereign’s grandfather, those were the two dates featured in the first two instalments. Viewed from abroad, 1964 is a crucial moment as it was when Japan returned to the international scene, culminating in the Tokyo Olympic Games (see Zoom Japan no.14, September 2013). We should remember that it was also the year that the Land of the Rising Sun joined the OECD, and inaugurated its first high speed train line between the capital and Osaka. In short, there’s no doubt that the 39th year of Emperor Hirohito’s reign is regarded as a date of great importance in Japan.

On the other hand, from the point of view of other countries, 1970 might be considered as less of a key moment in the country’s contemporary history. And yet, for very many Japanese, that year represents a complete change of direction, not like one of those gentle curves you sometimes encounter along a motorway, but rather a hairpin bend you have just negotiated on a particularly treacherous mountain road when your whole life flashes before your eyes. In fact, 25 years after the Second World War ended, it was a new Japan that presented itself to the population. At the very least, Japanese see that year as the start of a radical change in their lives. It’s not too excessive to apply the term “radical”. After all, the previous decade had ended in confusion with riot police breaking the student occupation of Tokyo University’s Yasuda Auditorium in January 1969. The arrest of some 600 young people during the police operation had appeared to put an end to several years of Japanese student protests. But despite peace and calm being restored to the campuses, the upheaval and violence continued, two striking examples of which took place in 1970. In early spring, the hijacking of a Japan Airline’s Boeing 727 en route to Pyongyang, North Korea, plunged Japan into an era of extreme left-wing terrorism, which continued for many years. A few months later, on 25 November, MISHIMA Yukio, the renowned writer and militant nationalist, killed himself in spectacular fashion at the headquarters of the Self-Defence Forces. This had a negative effect on the general public as the motives that impelled him to commit suicide no longer coincided with the aspirations of the Japanese people, especially Japanese women.

It was not that kind of radicalism that interested them. Instead, they were searching for a more radical form of freedom, that’s to say one that allowed them to express themselves more as individuals. After a quarter of a century of collective effort to rebuild the country, there was a desire for change and self-discovery. This found expression at the end of March 1970 when the magazine An An was launched, and which went on to have a revolutionary effect on the publishing world (see pp.6-8). The bimonthly magazine, which was intended to appeal especially to young women, chose to feature fashion, going out, travelling, and pleasure in all its forms in an original way and within a graphic framework free from many of the restrictions affecting most periodicals at that time.

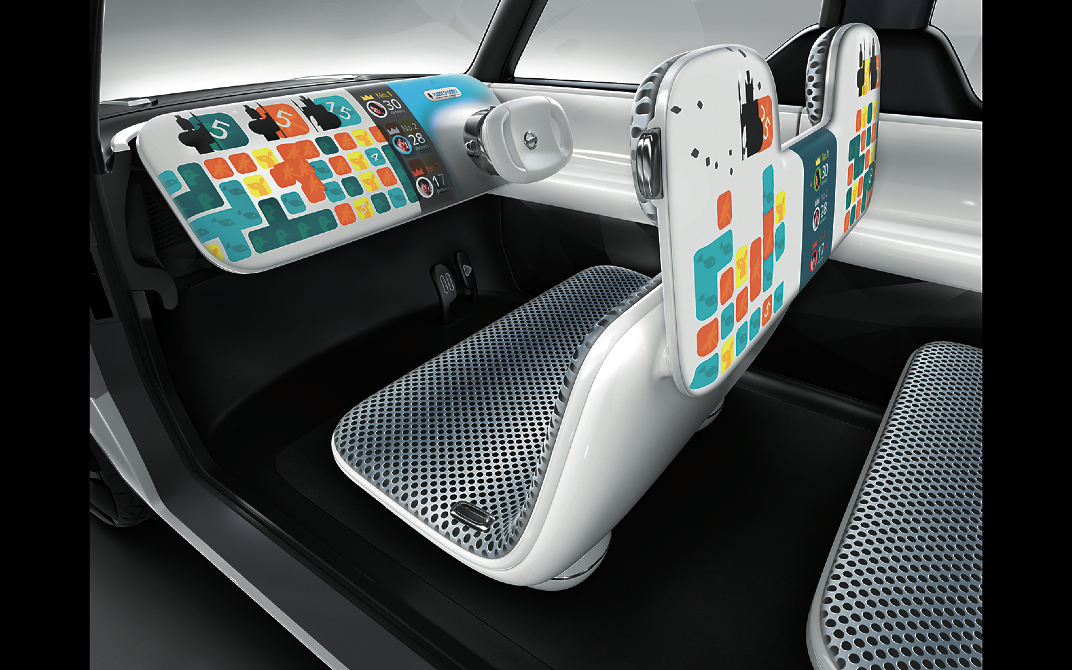

It’s interesting to note that it was a publication aimed at women that set the tone for this Japanese dream of a new Japan. Then, Expo 70 opened in Suita, a suburb of Osaka. Its theme “Progress and Harmony for Humanity”, also expressed a desire to move forward into a new world. More than 64 million people visited it during the 183 days it was open to the public. The symbol of Expo 70 was the Tower of the Sun designed by OKAMATO Taro, and also reflected this quest for something new that was driving the Japanese. In that respect, An An highlighted the important role of women. While men were being swept up by companies to become “good little soldiers” in the service of their country, women were in a position to take a step back or even maintain a certain degree of independence from a system that did not appear to represent them.

In a country with a tradition of women’s and feminist magazines – the first appeared in 1903 – An An has successfully reflected the changing role of women. Almost 90 years previously, HIRATSUKA Raicho had written in the first issue of the literary magazine Seito that “originally, woman was a real sun. She was a fully fledged being. Today’s woman is a moon. She depends on others to live; she shines thanks to the light of others; she resembles the pale face of a sick person”. It appeared obvious that the creation of An An heralded the beginning of long term change. In short, the magazine has always reflected the development of Japanese women as they became stronger and more independent of men.

Of course, it did not all happen at once in all areas of life. It was in the field of travel that a move away from accepted convention first began. While the new bi-monthly magazine encouraged its readers to discover new worlds, on 1 July 1970, Japan Airlines brought its first Boeing 747 into service. The era of the Jumbo Jet and the introduction of universal tourism abroad coincided with the launch of Japanese National Railways’ campaign Discover Japan in the autumn of the same year. Despite its English slogan, this scheme to promote travel in the archipelago was primarily aimed at the internal market. It was women, young women in particular who responded, once again demonstrating their desire for freedom. An An was again ready to accompany them on their journey. At the time, it was still an ephemeral kind of freedom as there was still considerable social pressure to get them back on the straight and narrow path leading to marriage. At this period, popular songs had titles such as Kekkonshiyo [Let’s get married, 1971] or Hanayome [The Bride, 1973], but you can sense that some of them wanted to break free from social conventions and go further in asserting their independence, particularly in terms of employment. Ten years after the first issue of An An appeared, another magazine marked this new turning point: the weekly magazine Torabayu, from the French “travail” (work), was launched in February 1980. It was aimed at the “working woman”, eager to show that she was more than just a simple consumer. The revolution continues.

ODAIRA NAMIHEI