It’s the younger producers who have been developing new cultivation techniques.

Even though the amount produced remains small, the conditions are in place to move up to the next level.

The time of Japanese wine seems to have come, at last. After being considered just an import market for European, American and Australian brands for many years, Japan is finally emerging as a producer of fine wines which are catching the attention of foreign experts.

It started in 2013, when a white wine from Yamanashi Prefecture, Grace Winery’s 2012 Gris de Koshu, won a gold medal at the Decanter Asia Wine Awards sponsored by the British wine magazine Decanter. But even before that, in 2004, another Yamanashi-based wine, Aruga Branca, had won a gold medal at a French competition. These early exploits silenced all those detractors who kept making fun of Koshu wines – first and foremost YAMAMOTO Hiroshi, who had famously declared that Koshu was “essentially without much personality – like Japanese women”.

The increasing popularity of Made in Japan wine is a fairly recent phenomenon, and the result of a number of factors. On the one hand, according to internationally famous sommelier and Vinotheque magazine publisher TASAKI Shin’ya (see pp.12-14), local media are always on the look out for the next big thing, and now it’s the turn of wine. Many magazines and websites run stories about local producers and advise their readers on how to match the wines with food.

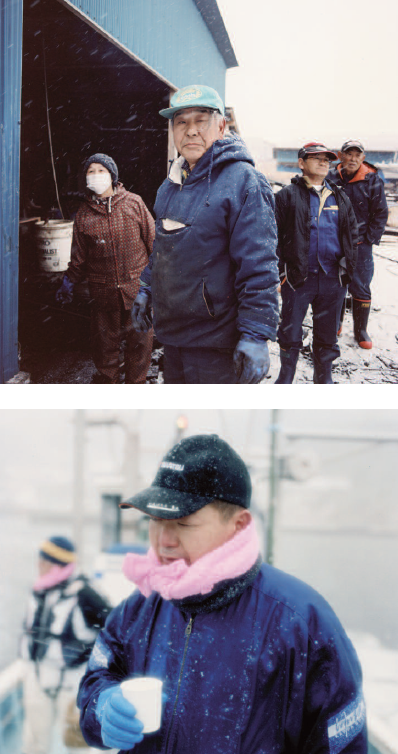

On the other hand, the wine-making industry has finally realised what it takes to raise the status of Japanese wine. For many years, producers followed decades-old, antiquated practices, remaining content just to supply their small local market. However, these people are now approaching retirement age (the average age of farmers in Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan’s top grape producer, was 68.2 in 2015), and are being gradually replaced by a younger generation that is not afraid of experimenting with new methods. Some farmers, for instance, are now planting vineyards at higher altitudes and in neat rows, European-style, instead of training vines over pergolas as was the custom. This is supposed to help the grapes ripen during Japan’s infamously wet summers.

ARUGA Hiro, a third-generation winemaker of the gold medal-winning ARUGA family, studied and worked in Burgundy before joining his father. ARUGA is part of a younger generation of producers who have studied in Europe and are now applying their knowledge to Japan’s different climate and environment.

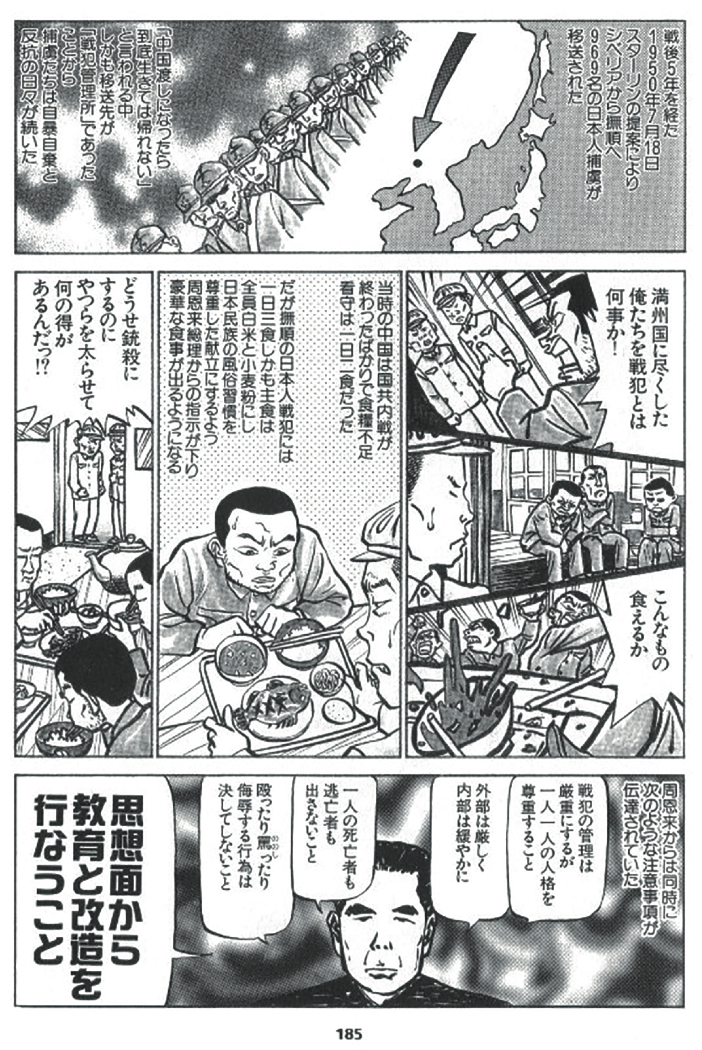

An important contribution to the international credibility of Japanese wine came last October when the government passed a new law that makes the important distinction between kokusan wain (domestic wine) and Nihon wain (Japanese wine). In the first category are those wines that are made from a mix of local and imported grapes. All these cheap wines, made by such big companies as Suntory, and Kirin’s Chateau Mercian, which can be found in every Japanese supermarket are domestic wines. “Japanese wines”, on the contrary, are made with 100% Japanese grapes. Besides, in order to get a DOC label, they must be made with at least 85% of grapes from their particular area.

Of course, strictly speaking there are no grapevines native to Japan: for example, DNA analysis at the University of California, Davis, showed that Koshu is a hybrid of mostly vitis vinifera (a variety of European grape like Chardonnay) and Asian grapes. However, the Koshu wine grape has evolved locally over many centuries, and is therefore considered an indigenous variety.

An increasing number of small wineries have taken up the challenge to produce high-quality, 100% Japanese wines. The domestic market used to be dominated by Suntory and other big companies, but in 2004 new regulations made it easier for boutique wineries to be set up. Previously, the law required a minimum production level, which was within the reach only of large corporations. This new competition seems to have had a positive influence on the mainstream companies, which are currently looking for ways to make better products. The four major beverage producers are also planning to double the acreage of their vineyards by 2027, which would amount to a little less that 20% of all grape cultivation in Japan.

In February, the Japanese government made a significant contribution to wine makers – and the wine market in general – when it signed an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the European Union to bi-laterally eliminate both tariffs and non-tariff barriers on wine and food imports. Until this year, tariffs of up to 94 yen (around £0.70) per bottle of wine had meant that the European market had been virtually closed to Japanese wines. While Yamanashi’s wine exports have increased 20 times in the last five years, their main foreign markets have been Asia and North America. In comparison, wine exports to the EU in 2016 amounted to just 10 kilolitres for a grand total of 15 million yen. The new agreement should help change things considerably in this respect. Of course, EPA works both ways, which means European wine imports will increase as well, but this new challenge should provide Japanese producers with a new stimulus to close the gap with Europe.

Views on Japanese wine changed when, in 2013, a wine made from the Koshu grape variety won a gold medal at the Decanter asia Wine awards.

Japan is still a newcomer in the international arena, and a lot of work is still required. According to a 2016 survey of the Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), for instance, Japanese wine exports amounted to a tiny 56 kilolitres in comparison with world heavyweights such as Spain, Italy and France, which exported 2.28 million, 2.10 million, and 1.50 million kilolitres respectively. However, while only 0.35% of local wine is exported, the percentage of Japanese wine sold on foreign markets has been steadily rising. Between 2015 and 2016, for instance, there was a 30% increase.

In the meantime, local consumers are finally paying attention to Japanese wine. Until 2003, it was still considered a novelty and even in Tokyo it wasn’t easy to find. These days, though, most shops carry at least a few brands, while several bars and restaurants are devoting all their shelf space to Japanese wine. According to a 2016 report by Wine Intelligence, the number of consumers who stated that they have tried local products rose from 21% to 27% in 2014, while more than half of the people surveyed said they had purchased Japanese wine in the past six months.

Local wine comprises about 5% of the total distributed domestically. Officially recognised “Japanese wine”, in particular, is less than 20% of the total wine made in Japan. These figures are still rather insignificant compared to Japan’s overall wine consumption, but those amounts are expected to rise in the next few years as the quality of local wine improves.

The recent wine boom has been accompanied by an upward trend in the quantity of wine grapes produced domestically. Not so long ago, Japanese farmers only produced dessert grapes, and the scraps and surplus output were used to make wine. However, a study conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries found that 17,280 tons of wine grapes were produced in 2015, the largest amount since 2003 when such statistics were first recorded. All in all, fine Japanese wine seems to have a bright future, especially after Koshu and Muscat Bailey A received the coveted award from the OIV. Their international success will surely encourage other wine makers to improve their production and labelling methods.

JEAN DEROME