Bottles of wine produced by Misawa Winery, Yamanashi Prefecture.

For some years now, the Japanese have shown a real interest in this drink with a chequered history.

For most Europeans who have never tasted or heard of Japanese wain (from the English “wine” to mean “wine from Japan”), that’s to say wine produced in Japan, to learn that local wine is currently much in vogue in Japan can come as a surprise, as though it was a trend that has appeared out of nowhere. It’s true to say that the history of wine in the Archipelago is relatively recent. Though wine production began in the Meiji era at the end of the 19th century, this heavenly drink has been slow to appear on Japanese tables as no-one had ever seen a red-coloured wine or a drink with a much more pronounced acidity than sake, even a slight bitterness… To accustom the Japanese palate to the taste, the producers initially added sugar and flavours to the wine, or grape juice and alcohol as well as sugar. Akadama Port Wine is the best example of these products. It is still marketed under the name of Akadama Sweet Wine.

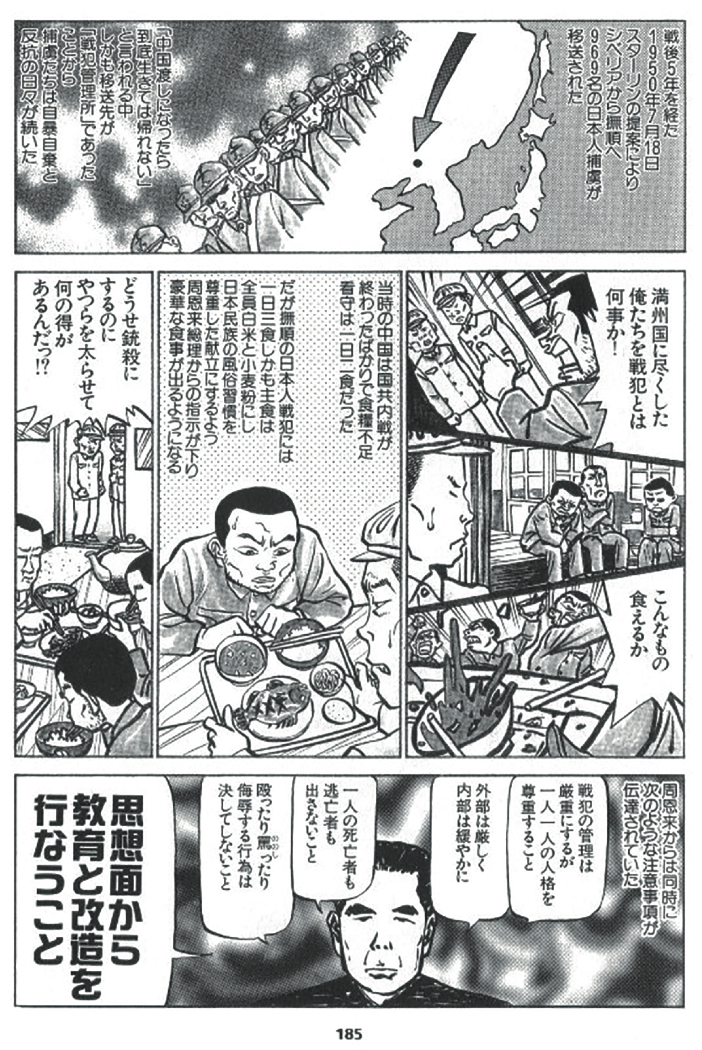

It was only in the 1970s that the Japanese slowly started to become acquainted with the world of wine. This process was greatly encouraged by the westernisation of the Japanese diet, and this was also when consumption of “normal” wine overtook that of sweet wines. However, what was produced in this period was far from high-quality wine. Crushed or damaged grapes including dessert grapes rather than wine-making varieties were used to produce somewhat watery wines. The Japanese were unaware they needed to cultivate grapevines specifically to make wine. In addition, Japanese companies were importing and blending cheap foreign wines, or buying grape juice concentrate from abroad, and adding water and sugar to cause them to ferment, so much so that for a long time it was Kanagawa Prefecture that produced the most wine, in the vicinity of the large city port of Yokohama. The factories manufacturing wine were built right next to the sea to avoid having to transport the raw materials too far. A drink that could not be called “wine” according to European standards flowed freely.

Many Japanese people remember these mediocre wines produced in the Archipelago, and can testify to their bad experiences. Though the grape juice was imported, it could be called kokusan wain, “wine produced in the country”, as part of the production process took place in Japan. For this reason, the genuine Japanese wine growers have fought for many years for the name nihon wain to be applied solely to wine produced entirely in Japan, using locally harvested grapes (a term in force since 2015), to differentiate it from kokusan wain, which still exists today.

TAMAMURA Toyoo, a pioneer in the field and owner of the Villa d’Est Winery, who is also a celebrated author of numerous books on gastronomy as well as French life, has all the facts surrounding the arrival of wine in Japan at his fingertips. Moreover, he remembers the 1970s well, when the Japanese were still unfamiliar with wine. He’d just come back from a period studying in France and at that time, in Japan, the wines on sale were either very expensive or popular Californian wines. Once, when the wine was clearly corked, the vendor would not admit it and argued that “it’s the acidity that gives the wine its character…”

The assumption that the climate in Japan was not conducive to the cultivation of vines was a long-held belief among the Japanese themselves. It’s true that rainfall is relatively heavy, and the humidity causes diseases to spread and insects to proliferate. Nagano is nowadays considered to be one of the foremost wine producing regions in Japan, but TAMAMURA was discouraged when he moved there in the 1990s. He was told that the climate was too cold and humid to grow grapevines… “I was able to start producing wine despite all the negative advice because it began as a ‘hobby’ rather than my main source of income. I planted five hundred vines thirty years ago and gradually extended the area of land under cultivation until today, when we have eight hectares of vines,” he says with a smile.

Thanks to its particular geographical situation, Japan has a very varied climate, which gives wine growers a wide choice of possible locations. Nowadays, wine is produced in very different regions. Admittedly, more than half of the production still takes place in the prefectures of Yamanashi and Nagano, traditional grape-growing areas. But according to KAKIMOTO reiko, a journalist and Japanese wine expert, Yamagata Prefecture could prove a promising area for wine production due to climate change, and northern regions like Hokkaido, where the number of wine producers is increasing, has the advantage of large areas of land. Producers are even setting up in the west of the Archipelago, in Okayama for example, and as far south as Kyushu Island.

“Look at the United States. Wine is not produced just in California but in very varied climates, from the north to the south, in Oregon, Texas and Arizona. Wine can be produced anywhere in the world. It’s a simple matter of taking greater care of the grapes in certain regions, as we do in Japan. Having a good knowledge of local climate conditions allows us to choose the appropriate grape varieties. It’s our job to make the best choices suited to our location for each stage of production,” observes TAMAMURA.

Behind the current craze is the soaring number of producers, which is rising sharply (191 in 2014, 303 in 2018) for bureaucratic reasons. In Japan, there are very strict legal requirements before a licence to produce alcohol can be obtained. In the case of wine producers, a minimum of 6,000 litres (8,000 bottles) has to be produced in the year after obtaining the licence. But since 2002, the government has introduced a system of “exception zones”, and a softening of the rules to help in the development of several areas of production. Since then, it has been possible to ask for a licence even for a small production of 2,000 liters (2,667 bottles). The introduction of this system has, in turn, pushed banks into easing their loan conditions. To begin producing wine requires a pretty large investment (acquisition of land, plants, machines…), and lowering the threshold was favourable for producers and allowed wine to be produced in small quantities using traditional artisanal methods.

As a consequence, the variety of products has increased. “Over the last ten years, we’ve witnessed a drastic change: more producers, more vineyards, more grape varieties, more vintages. And the profile of the producers is also very varied. Some have trained in Europe or have studied at European universities, others are self-taught by doing research online…,” says KAKIMOTO.

Of course, when speaking of a “boom” in Japanese wine, it’s necessary to qualify the statement. Just like the vogue for sake in Europe, which is more evident in the media than in concrete sales figures, a Japanese person only consumes 3.5 litres a year on average, Japanese and foreign wines combined. The sale of fruit based drinks (apples, grapes) generally only represents 4.4% of the total volume of sales of alcoholic drinks, and Japanese-produced wine is only 30% of these sales. Nihon wain only represents 20% of the wine produced in Japan, the rest is still wine made from imported grape juice or blends of wine from abroad. You can quickly do your own calculation…

At the same time, the numbers of producers have increased considerably. Most of them are small-scale producers, and as aficionados of Japanese wines become more numerous daily, some producers often run out of stock. Some bottles have attained a mythical quality, so are very rare. It’s a complicated situation. Some people say that this trend has already peaked, and it’s mainly those working in this field who advise caution. They have experienced several periods of growth when they thought that the world of wine would take root in the Archipelago, and each time, they have been disappointed.

But this time, the situation is undoubtedly different. In other areas such as cheese or sourdough bread, these traditional handcrafted products which can accompany wine are increasingly made by the Japanese themselves. The younger generation is more aware of having to reduce “food miles”, and the human element must not be forgotten. KAKIMOTO has noted that easy access to producers is very important for enthusiasts of Japanese-made wine. They can visit the vineyards, talk about the wine with the producers, feel a connection with the bottles whose labels are written in Japanese. It’s the same relationship the French have with their local wines. The feeling that it’s all about “their” wine encourages loyalty towards to the producers. For far too long, the large wine companies in Japan that have been content to produce lowquality wine are finally turning to “real wine”. They have begun to plant grapevines and now produce two types of wine: popular wines like they have always done, and good quality wine. Bruce Gutlove, a New Yorker who studied food science and brewing at the University of California, moved to Hokkaido thirty years ago, and has trained many Japanese producers. Under his influence, these young producers called “Bruce children” are making outstanding wines. ASAI Usuke, the legendary winemaker and author of numerous books about wine, who is nicknamed “the father of of contemporary Japanese wine”, also contributed to the emergence of numerous “Usuke boys” who now produce internationally renowned wine. Another example is the Domaine de Montille in Burgundy which recently decided to create a vineyard in Hakodate and sent 50,000 grapevine plants. We can only hope a revolution is underway.

For a long time, it was considered that the climate and topography of the country were not suitable for wine production.

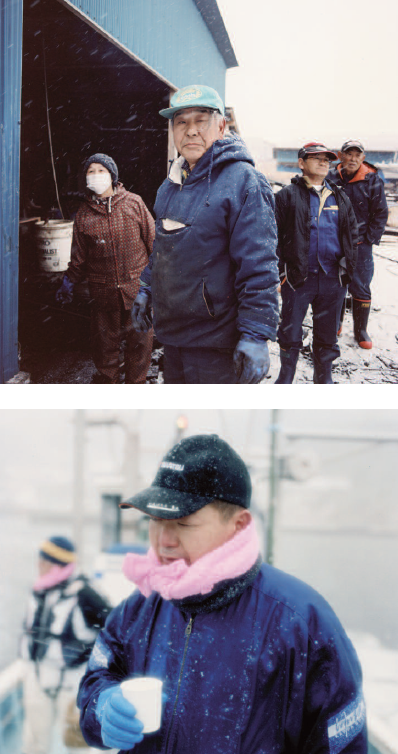

It has to be said that the work that someone like TAMAMURA has undertaken over many years to popularise home-grown wine has borne fruit. Through his writing, he has conveyed not only his love of wine itself but also what it entails becoming a winemaker or going to live in the countryside with concrete examples. In some of his books he details the extremely complex legislation of Japan’s administration in addition to the steps to follow to produce wine, providing guidance to those who want to plant vineyards as well as informing the general public. The triple catastrophe on 11 March 2011 obviously played a part in changing the outlook of Japanese people. He recounts how before these events it was principally men in their forties or fifties, wine lovers from quite wealthy backgrounds (doctors, lawyers or those working in finance…) who were redeploying into wine by investing what they had earned. Yet, over the past eight years, more and more young couples have been settling in different regions to focus on agriculture. Beforehand, women were somewhat reluctant to follow their husbands’ “dreams” of making wine… Today young women, concerned about the environment in which their children will be growing up, can take the initiative in this new way of life. The figures prove this: 30% of the winegrowers producing wine are women.

“The whole process of wine production could be the most up-to-date in the world”. This is often said by people working in the Japanese wine industry. Production techniques, mistakes to avoid and other advice is easily found on free online sites. Men and women both take part and communicate straightforwardly and openly. In Japan, this online community has only recently appeared and has managed to avoid the previous macho and exclusivist practices in some traditional working environments in the country

Some people maintain that the cost of Japanese wines, which are not necessarily the cheapest taking into account the workforce required, might limit their growth in popularity. But it’s not that Japanese wine costs so much, rather that other alcoholic drinks in Japan are not “so expensive”. Bottles of wine sold in supermarkets, whether it’s kokusan wain or foreign wine, sometimes cost only 500 yen (£3.50). The price of a 350 ml bottle of alcohol is 100 yen (less than £1) in a konbini, one of those convenience stores that open 24/7. This is why it’s difficult to persuade people that wine can be quite delicious but that a bottle can cost almost £20. The sake producers also complain about the situation. High-quality sake is still affordable in comparison to European wine, but the Japanese still think it costs too much.

As strange as it may seem, the Japanese did not pay much attention to what they were drinking for a long time. The great wine collectors are the exception. Alcohol was a means of communication between men who “went for a drink” while eating very little. This habit has not died out completely. An employee in a large company in the alcohol industry once confided in me: “when we look at our bestselling products, it’s apparent that most Japanese only want to get drunk…” This year’s EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) has removed import tax on European wine, thus lowering its cost, and resulting in even fiercer competition.

Japanese wine expert TAMAMURA Toyoo is committed to the continuing improvement in wine production.

When someone from abroad visits Japan, they tend to want to immerse themselves completely, going to izakaya (Japanese style bars) and ordering sake… But those who know a bit about the country are aware that Japan has built its identity by assimilating foreign elements and influences. So why limit yourself to sake, beer and Japanese whisky, the last two of which are drinks of foreign origin? For those who want to discover Japanese wine, TAMAMURA suggests asking if they have Japanese wine on their menu. Sadly, in supermarkets, one can still stumble across wine produced in Japan that’s not worth drinking, but that’s not the case for wine selected and served by restaurants. If foreigners express an interest, it might encourage them to include it on their menu. Despite the reticence and resistance of some, things are moving forward. Since the appearance of his landmark creation Chikuma Wine Valley six years ago, TAMAMURA has completed most of his planned projects. His “wine academy” attracts those who want to immerse themselves in the work of wine growing, and his former students are already producing wine. He has also refurbished a former shop in the village, which previously belonged to a sake retailer, to revive this once lively meeting place for the villagers. In the same village, with the help of the inhabitants, he has transformed an old traditional house into an inn to encourage wine tourism. It’s been a surprise how rapidly he has managed to implement these projects. But he agrees that to build some momentum within the community, he first needed the support of the local authorities who were able to conceive a plan (rejuvenate the population, welcome new farmers, design an ecotourism village, for example). And this support was a thousand times more important when he added that, to ensure the region could produce high-quality wine in the long term – it should have a training centre, a university with a department of oenology and agronomy, specialising in fermentation and brewing.

“There are those who question the sense in bringing together several producers in the same area. But I can only see advantages to the idea. Even if the soil composition and climate is identical, the wine produced will be entirely different according to whether the soil is exposed, the type of grapevine used, when the harvest or the wine-making takes place. There’s not only one solution, there are only ever changing circumstances. That’s what’s so exciting about it: a bottle of wine is both an expression of the terroir and of the person that makes it. Many of the wine producers I know, who are still far from making a fortune, agree that after a hard day’s labour, their fatigue disappears when they contemplate their vines. To work in agriculture you need a beautiful view, a beautiful vision. The result of your work in the landscape,” he says.

“What’s fascinating about wine, is that nothing remains the same. Even the same producer using the same grape variety will always have surprises. Whether you open a bottle, or leave the bottles to rest in the cellar… Life is never routine with wine, and it’s especially gratifying to be part of the breathtaking new developments in Japanese wine,” adds KAKIMOTO with passion.

Decades of effort by wine producers lie behind the current craze. “What’s good about wine is that growing grapevines gives you a long-term perspective. To produce wine, you first need to plant the vines, then wait five years before it’s possible to harvest the grapes. The bottles will mature over time, and the vines will still be there after I’m dead. After my death, it would be wonderful if my village continued to look after my vines until a sign appears stating ‘apparently, someone called TAMAMURA planted them here…’,” declares TAMAMURA smiling.

SEKIGUCHI RYOKO