Many Japanese have discovered a growing number of foreigners working in their local convenience stores…

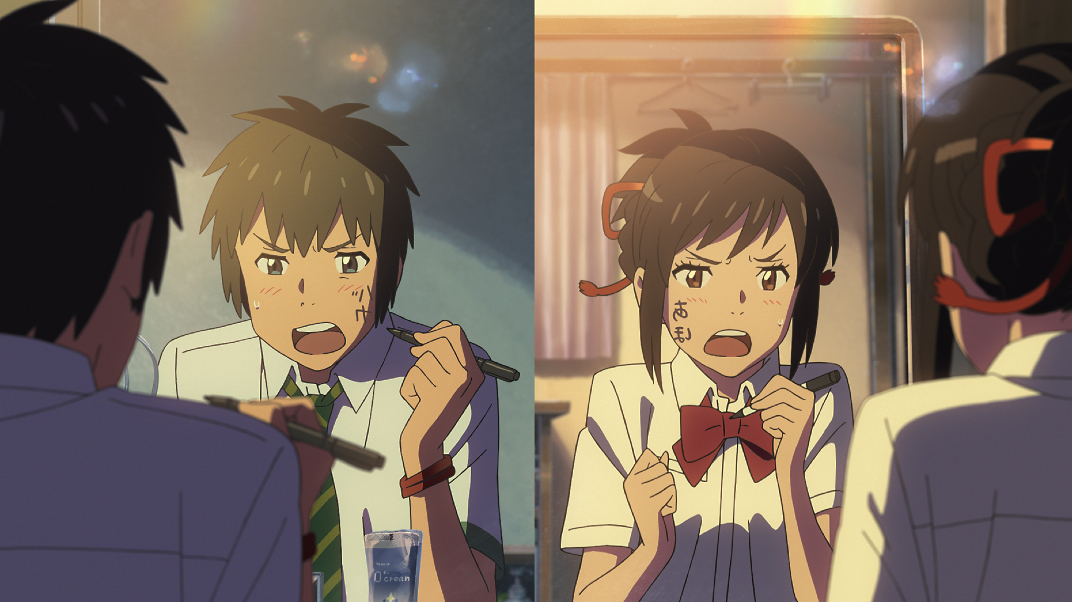

The face of Japanese convenience stores is changing, literally. More and more often the cash registers are operated by foreign students who work part time in the ubiquitous konbini, as the stores are called in Japan. Zoom Japan discussed this new phenomenon with writer SeRIzAWA Kensuke, the author of Konbini Gaikokujin (Convenience Store For- eigners), who spent one year researching and talking to these people.

How did your book come about?

Serizawa Kensuke: In a sense, this project began after the triple disaster took place in Fukushima in March 2011. At the time, I was living near Asakusa, which, as you know, is one of Tokyo’s most popular tourist spots. Suddenly, all the foreigners disappeared, driven away by fear of nuclear contamination. About one year later, I began to notice a new type of foreigner: not tourists, but young people working in convenience stores. They kept growing in number, and I saw them everywhere around Tokyo. I wondered where they were from, and my curiosity slowly morphed into an idea for a book.

I guess you eventually found out from where they came.

S. K.: At first they were mostly Chinese, and even now they make up the greater number. Then you have a lot of people from Vietnam and Nepal. All in all there are about 50,000 foreigners working in convenience stores around Japan. In many shops, most or all of the employees are not Japanese, sometimes including the store manager.

On average how much does it pay?

S. K.: In Tokyo, it’s a little more than the minimum hourly wage, which is around 958 yen (£6.70). Outside Tokyo, it’s even less.

These days, it seems that the Japanese avoid this kind of work like the plague. I heard of a shop owner who failed to hire a single person in a whole year.

S. K.: even my nephew, who is 20, says he doesn’t want to work in a konbini. For that kind of money, working in a restaurant or a karaoke is much less difficult. On the other hand, let’s not forget that the Japanese workforce is shrinking as a whole. There are fewer kids in their teens and 20s, which makes finding new employees even harder.

For many Japanese students, working in a convenience store used to be a sort of rite of passage. Have you ever worked in a konbini?

S. K.: I tried. And I failed (laughs). I did the interview, but I was told I wasn’t the right person for that kind of job. Considering what I’m doing now, they were probably right.

Konbini work seems to be quite hard, doesn’t it?

S. K.: It’s certainly hard and complicated. It goes well beyond just working the cash register and putting products out on the shelves. You must be able to do many detailed tasks, from handling parcel delivery invoices and utility bills to accepting different kinds of payment: cash, credit cards, now even smartphone- based electronic payments. Plus the money is not good.

So why do so many foreign students apply for this job?

S. K.: I guess, for them, coming from poorer countries, the pay doesn’t look so bad. Another appealing feature of this job is that they can interact with local customers, which gives them a chance to practise the Japanese they’ve been learning. If they don’t speak it well enough to be employed in a konbini, they work on factory conveyor belts or the tedious job of onigiri or bento making. If, on the contrary, they are particularly fluent, they may work in hotels.

Do you mean most of them are students?

S. K.: A lot of them are students, of course. Japanese law is not as strict as other countries (in the US, for instance, you can’t work at all) and allows foreign students to work up to 28 hours a week. even this law is loosely enforced, so there are people who actually work longer hours, especially if a store doesn’t have enough shop assistants. It’s a win-win situation: the owner has all the slots covered, and the shop assistant can earn more. As a consequence, there are people who originally came to Japan to study, but end up working more and studying less.

I’m sure that studying in Japan must be very expensive for people coming from Nepal or South-East Asia. Does that mean these foreign students come from rich families?

S. K.: Of course, some of them are wealthy, but they seldom need to work in convenience stores. For most of the others, the only way to study at a Japanese language school is to borrow money because one academic year costs as much as 1 to 1.5 million yen (£7,000 to £10,500). It’s a huge sum for those people. Their families are often forced to sell part of their land to send them abroad. In the end, they neglect their studies and end up working longer hours. The result is that the number of successful applicants for student visas from such countries as Bangladesh, Myanmar and Uzbekistan has sharply declined lately as the Japanese government is trying to clamp down on people who abuse the system allowing them to work.

You said that the opportunity to improve their language skills is one of the reasons foreign workers are attracted to this job. What are the negatives? What problems do they experience?

S. K.: First of all, they experience racism and discrimination, mostly from the customers. “Speak properly” or “I don’t understand what you’re saying” are among the things people say to them. At other times, they’re criticised for being too slow or not understanding what the customer says. Then again, in recent years, customers in this country seem to have become quite selfish and bad-mannered in their dealings with shop assistants. This, of course, doesn’t excuse their racist attitude towards foreigners.

Do you mean to say that the Japanese are racist?

S. K.: Let’s say that, even now, many Japanese people have few opportunities to interact with foreigners, nor seem to be eager to look for these opportunities. You can see how people are startled when a foreigner asks for information in the street, or they say, “sorry I don’t speak english” even though the foreigner has spoken in Japanese. Too many people in Japan still think that a Japanese citizen must look a certain way to be considered truly Japanese. For example, you can’t be black and Japanese at the same time – unless you’re called OSAKA Naomi, of course.

I understand that linguistic intolerance exists even towards other Japanese people.

S. K.: Yes, you’re right. Standard Japanese, or “NHK Japanese”, is the only acceptable way of speaking. If you come from Tokyo and speak with a local accent, they make fun of you and treat you like a hillbilly. In this sense, having more foreigners working in shops may be a good way to open up Japanese society.

The government doesn’t seem to care what happens to overseas workers once they arrive in Japan.

S. K.: Obviously, the government is largely responsible for helping foreigners settle in Japan, but politicians and local authorities can’t do everything. I believe the time has come for society at large to become more involved through NPOs and other projects. We need to make an effort to realise “beautiful harmony” (Reiwa) – to mention the english translation of the new era name.

Have there been any significant changes since you published your book?

S. K.: In the last few months, there have been two major developments: on the one hand, all the major konbini companies have decided to experiment with shorter opening hours. According to last year’s survey, 61% of franchise operators say they don’t have enough workers and have to work themselves, sometimes 16 to 18 hours a day, in order to keep their business going. Some time ago, a shop owner in Osaka decided, of his own accord, to close his store at night because he couldn’t afford to keep it open 24 hours a day. Connected to this change, we may see fewer foreigners working in convenience stores due to shorter opening hours. There are other reasons, unrelated to the convenience store business, that may discourage foreigners from coming to Japan in the future. The first one is the money required to enrol at a Japanese language school: as I said, it often proves to be too big a debt to deal with. As re- turning students spread the word about life in Japan, other people may conclude that studying in this country is not worth the effort. The last important reason – I’m talking about immigration in general, not just studying in Japan or working in a konbini – is that people from other Asian countries are already being attracted by higher salaries and better working conditions in China and Korea. Particularly in Korea, the state is working hard to welcome immigrants. However, Korea is a small country and can only take so many people from abroad, so Japan may still be in with a chance.

What has this project taught you?

S. K.: Above all, I learned to be kinder towards people who work in konbini. Another thing is related to what I said earlier about expectations: when I was researching my book, I always approached non-Japanese looking people to ask if I could interview them. Then I realised that not all these people who “looked different” were foreigners. In other words, I was judging them by their appearance. I don’t consider myself a racist, but there are things we do all the time, unconsciously, that are actually a form of discrimination. I hope that future generations will not make the same mistake.

INTERVIEW BY GIANNI SIMONE