According to YuAsAMakoto, Japan has been too slow taking into consideration the rise in poverty in the archipelago.

Yuasa Makoto in Paris in March.

In September 2017, Zoom Japan devoted an issue to the problem of poverty in the Archipelago. Last year, KORE-EDA Hirokazu’s film Manbiki kazoku (“Shoplifters”) was awarded the Palme d’or and opened the public’s eyes to the phenomenon in Japan. 10 years ago, YUASA Makoto published Han hinkon: Suberidai shakai kara no dasshutsu (“Against Poverty in Japan”– not available in English) in which he raised public awareness of the situation in Japan and called on the authorities to take stock of the problem, which had been on the rise throughout the Heisei era (1989-2019). Based on his experience and his commitment to fighting against this impoverishment of society, he takes an uncompromising look back at the past three decades in the hope that the next era will be one of greater solidarity.

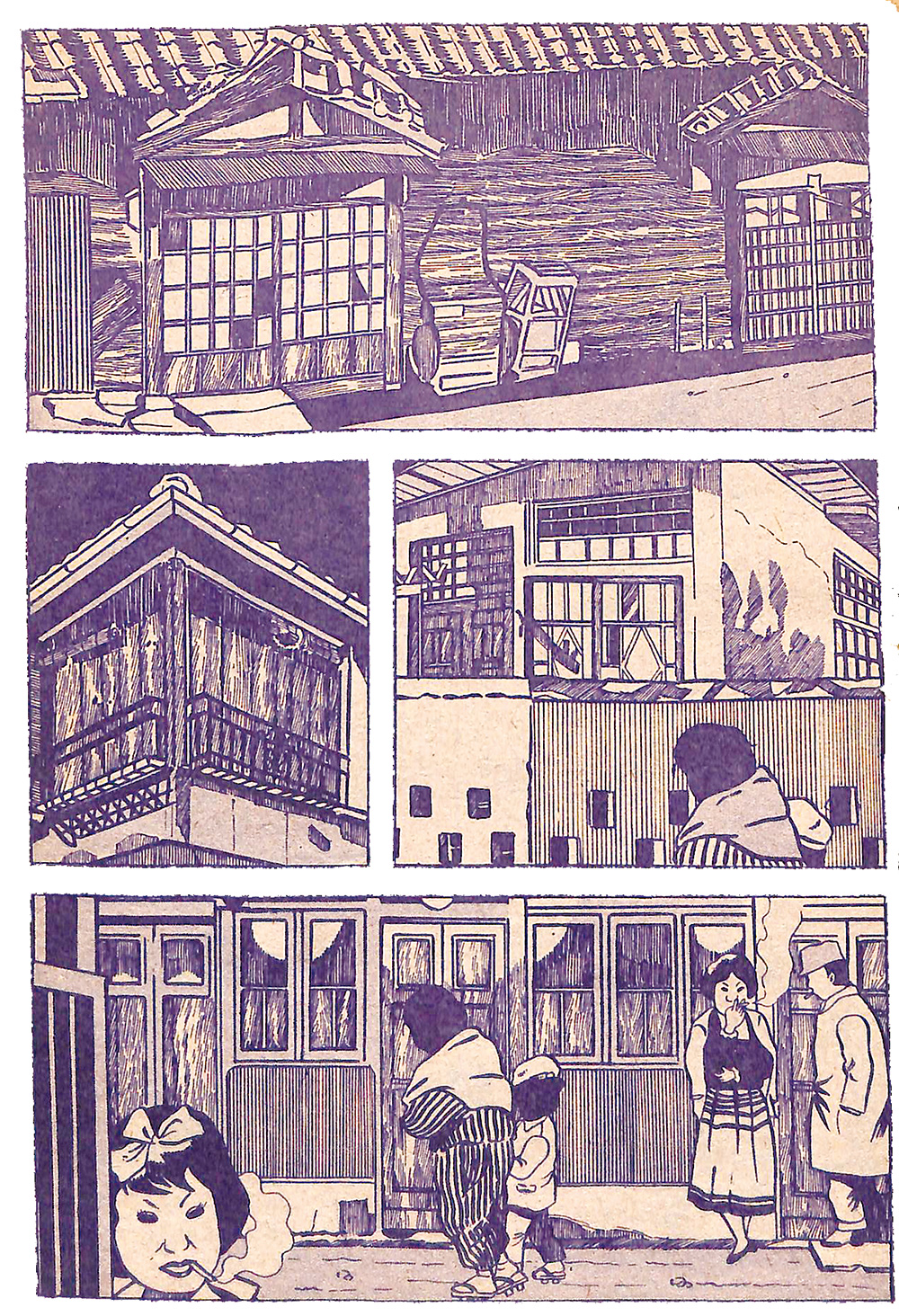

The showa era (1925-1989) was called the the era of the mass middle-class (Ichioku sochûryû jidai). With the publication, in 2017, of AMAMIYA Karin’s book, whose title could be translated as “The era of mass poverty” (Ichioku sohinkon jidai – not available in English), do you think the Heisei era will be remembered as a period of widespread impoverishment in Japan?

YUASA Makoto: The Heisei era began in 1989 and just afterwards, we witnessed the collapse of the speculative bubble. It was at that time that we first started to see a number of homeless people on the streets. But the phenomenon was not well understood for many years. People thought that it was all about“strange” or “odd” people who didn’t wish to find accommodation or work. Simultaneously, we saw the appearance of “freeters” [a term formed from the English word “free” and the German word “arbeiter” (worker)], that’s to say young people not in regular employment (hiseikikoyo), but we failed to understand how widespread the situation was. That’s why I think that the Heisei era, which has lasted 30 years, can be divided into two: the first twenty years during which the problem of poverty was completely hidden and the last ten years when people have started to become aware of it.

How did you come to consider the question?

Y. M.: When I began to become interested in the subject, I didn’t think that it was a question of poverty, but rather a kind of discrimination. It was only in 2006 that I used the word “poverty” in relation to the problem. It coincided with the end of the KOIZUMI Jun’ichiro government, which over 5 years had introduced numerous neoliberal reform policies, in particular making the Japanese social model more flexible. At that time, when I raised the question, people often retorted that this only concerned a few individual cases. However many examples I quoted, I was told they were only isolated cases. In 2009, that changed when the government published the levels of poverty for the first time. It was 16% at the time, which meant Japan was the fourth worst country in the oECD, ranked just behind Turkey, Mexico and the united States! Things changed then as society could no longer deny that the phenomenon existed now that there were the official figures. They also revealed that poverty particularly affected many women, the elderly and children. People also realised that there were different categories of poor people and it was not just about isolated cases as had been claimed. Awareness of the problem didn’t mean that the situation improved. Though some laws and measures were introduced in an attempt to correct the situation, they were mostly unsuccessful.

Can you explain why the Japanese have a tendency to deny the reality of the situation?

Y. M.: One of the reasons that immediately comes to mind is that it’s very painful to accept there are problems in society. There’s always a tendency to want to believe that all is well. And when “we are shown” that things are not going so well, it’s easier to convince ourselves that it’s what people want. when you see a homeless person, you wonder how it could have happened, why are they sleeping in the street, should you speak to them? People’s minds are bombarded by a load of questions and it makes them feel uncomfortable. So one solution is to say that it’s the homeless person’s problem. That way, it’s easier to explain things, to clear oneself of any responsibility. In my book, I raise the question of “individual responsibility” (jiko sekinin). The term usually means being responsible for one’s actions; I think it’s essential to try to take responsibility for one’s actions. But in the context of Japan today, it seems to me we use this idea as an excuse not to help others – if the other person is poor, it’s their fault, not mine. It’s not my responsibility, it’s theirs, that’s what I call tako sekinin (in reference to the expression jiko sekinin). For me, it expresses a societal or collective irresponsibility, whichever you prefer.

The case of “freeters” is interesting. The term, which appeared in the 1980s, refers to young people who refuse to sign conventional work contracts, and reflects the precariousness of the situation now.

Y. M.: You must remember that the term was coined in 1985 by the Recruit company, which specialised in recruitment, to describe people who refused to be bound hand and foot to a company. Many of them found they were not offered regular contracts. In reality, I don’t think they were refusing to have permanent contracts or be regular employees, they just didn’t want to devote their whole lives to their company. That generation of young people refused to follow in the footsteps of their parents who “had done just that and devoted their lives to their company.” They had watched their fathers work their fingers to the bone and sacrifice themselves no matter what the company demanded. Many young people did not want to work in that way. But with the collapse of the economic bubble at the start of the following decade and the resulting crisis, the use of non-regular contracts gained ground and affected an increasing number of men, which was something new. Basically, lots of people just didn’t want to devote their whole life to a company, but their precarious situation was exacerbated and they were viewed negatively by society in general.

Ultimately, it’s connected to the relationship the Japanese have with work. over time, work in Japan has become divided into two halves. There are the regular workers whom I consider to be the “super regular workers”. They work full-time, are promoted on the basis of seniority, different life events are taken into consideration (marriage, birth, children’s education, etc.), and they benefit from a high level of social protection. In exchange for this protection, people invest a great deal in their work. Conversely, non-regular workers are in a much less advantageous position. Their salaries are much lower and they do not benefit from the same system of social security. Even if they are doing the same work, due to their status, they have far less protection. And it’s very difficult for them to live on an hourly wage of ¥1,000 (£6.89). you should be aware that, today, 40% of employees in Japan are non-regular workers, which is a vast number.

This precarity of part of the population has many negatives consequences. One of the main ones, it seems to me, is the decrease in the birthrate in so far as births outside marriage are uncommon in Japan. And it costs a lot to get married…

Y. M.: Absolutely. what’s more, a few days ago, I met some members of the Liberal Democrat Party, which is Prime Minister ABE Shinzo’s party, to discuss the connection between poverty and the fall in the birthrate. As a matter of fact, everyone is waiting for a third baby-boom. we’ve known for a long time that we have an ageing population, but many demographers are of the opinion that there will be a third babyboom to counteract the decrease. But the figures are obstinately static and show that it hasn’t happened and that it will not take place. The main reason for the absence of a demographic rebound is connected to precarity and the increase in the number of non-regular workers. we know, for example, that men and women between the ages of 35 and 40 who are still living with their parents and remain unmarried represent around 3 million individuals. These people are non-regular workers and do not have the means to live independently. They are not having children. And without children, there is no baby-boom. The politicians appear to be looking for an answer to the problem, but I think it’s much too late. These people belong to the generation that experienced what is called Yuasa Makoto in Paris in March. Gabriel Bernard “The Ice Age of employment” in the mid 1990s, and in addition to having to live on much lower wages, they live with a lack of social acceptance. In the sense that the model of Japanese society is based on the idea that it’s the man who earns the entire household’s income, it means that to be a “man”, you have to be up to the task. Consequently, any man unable to achieve this is denied this status. So it’s important to keep in mind that people today around 40 years of age have lived with this stigma for the past two decades and have suffered a great deal. I think it would take the same length of time they have suffered for these people to reestablish themselves. If they’ve suffered for 20 years, they will need 20 years to recover. They’ll then be around sixty years of age, which is far too late to have children. That’s why it is essential for society to be committed to helping them become wholly re-integrated, above and beyond their simple economic role. There’s a need for places where they can meet socially to enable them to at least receive the social recognition they’ve been lacking. They must be re-energized so that they can start again, otherwise, the future demographic of the country will be well and truly compromised.

Just as the Heisei era will finally be characterised by its recognition of poverty, do you think the next one, personified by emperor Naruhito, will be one of solidarity?

Y. M.: I really hope so. I’ll do everything I can to make it so. I’m the manager of an association in charge of canteens for children (kodomo shokudo), which aim to provide meals for underprivileged children. During the past three years, some 3,000 similar places have been set up across the country. The people working there are not militants, just ordinary citizens who have realised that solidarity is the only possible response to this problem. This movement is a good example of how the upcoming era of solidarity could function.

In any case, it illustrates a general rise in awareness of the problem of poverty after years of denial… Is it possible to catch catch a glimpse of the kind of solidarity and support that formerly existed at the heart of village life?

Y. M.: There are similarities, but I see a marked difference. Today’s concept of solidarity is more inclusive than that found in traditional village communities where there was little consideration for the needs of women and children. Nowadays, most communities are created with women and children in mind. That said, there are also district associations, closer to the model of these famous village communities, which have helped set up canteens for children. I’m really delighted to see the old model evolve and become adapted to new forms of solidarity.

KORE-EDA Hirokazu’s film “Shoplifters”, winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2018, gave numerous Europeans the opportunity to learn about poverty in Japan. It was released in the final year of the Heisei era; do you think it’s a work that will come to symbolise the era?

Y. M.: This film could indeed be considered as a symbol of the past 30 years. Certainly, there’s been an increased awareness during the last decade, but I think that nothing will change if the public services don’t play a larger part. Indeed, the film highlights the lack of support from the State. The protagonists do all they can to sort themselves out in their own way. They each have their individual methods of coping. This problem has been around for 30 years, and the public authorities are still nowhere to be seen. our greatest challenge is to reintroduce public services and take practical action to improve the situation of these deprived people.

Now that Japan is getting ready for a new Imperial era, the government hopes to change the immigration rules. Don’t you think that these foreign migrants might be caught in the poverty trap if there were an economic downturn?

Y. M.: It’s definitely something to worry about. The government continues to say that it’s not about an immigration policy. They put forward the idea that people come to Japan, work here for 5 years then return to their own country. In reality, no one really knows how things will pan out. The possibility remains open for family members to come too, but we still have no idea how this might work out. By not admitting it’s about an immigration policy, the government is taking no steps to encourage the integration of these migrants. For instance, there are no plans to teach them Japanese, which won’t help them integrate, rather it will encourage their exclusion, even push them into poverty in the event of difficulties. Luckily, in some places there are cultural exchange centres to help make good some of these discrepancies.

These problems have been around and have been on the increase over the last decade or so. But there’s still a tendency to deny the reality of Japanese people living in poverty. For example, there are schools around Nagoya, where there’s a large community of Latin American migrants. Many of them are the descendants of people who emigrated to this part of the world at the start of the 20th century. 50% of the children there do not have Japanese nationality. There is no requirement for them to lean Japanese. They find themselves in an education system which copies one to teach disabled children. Many of them have no access to mainstream schooling and are trapped up a blind alley in Japanese society. This has been the situation for a good twelve years, but the government shows no interest in doing anything about it. I don’t see how things can get better if they remain vague about how they intend to deal with immigration. The risk of increased poverty and exclusion can only get worse.

INTERVIEW BY GABRIEL BERNARD