It’s taken 30 years for the otaku subculture to become established, both in Japan and the rest of the world.

Neon Genesis Evangelion by ANNO Hideaki was first broadcast in 1995.

The Heisei period witnessed the advent of an otaku Golden Age that has taken not only Japan but the whole world by storm. Nowadays, the words manga and anime can be found in most dictionaries, otaku culture is celebrated at countless conventions around the world, and Japanese comics and animation are widely available in many languages – not only the giant robot sagas that first became popular in the west but even shojo manga (aimed at teenage girls) and “boys’ love” stories. However, the Heisei period started in the worst possible way for the otaku community: the new era was only six months old when, on 23 July 1989, MIYAZAKI Tsutomu was arrested for sexually attacking a schoolgirl, and later confessed to murdering four children aged between 4 and 7, and sexually molesting their corpses. The police found 5,763 videotapes in his house including many anime, slasher and horror films, prompting the media to call him the Otaku Murderer.

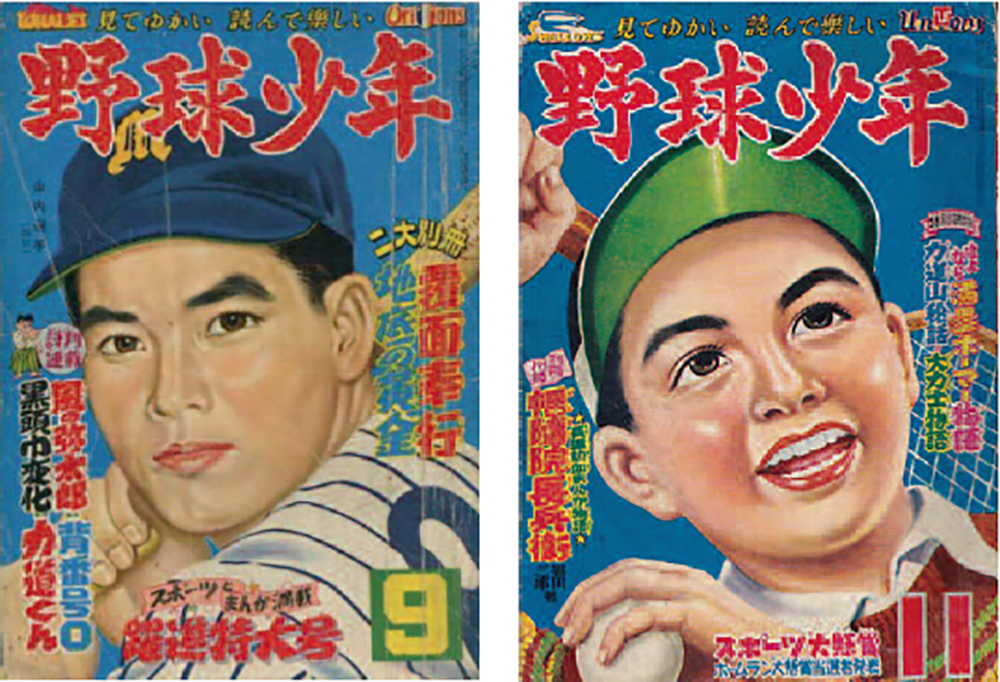

Public opinion of manga, anime and video game fans hadn’t been positive to begin with – the word otaku itself had been used first in 1983 by essayist NAKAMORI Akio to describe all “socially inept young males” who, according to him, were guilty of seeking refuge in a fantasy world made up of toys and cute girls. However, MIYAZAKI’s murders made things much worse, creating the idea that young people involved with anime were dangerous, psychologically disturbed perverts.

Back in the late 1980s and for most of the 1990s, being an otaku wasn’t something one could openly share with other people. Otaku typically occupied the lower ranks of the school hierarchy; they were bullied by other boys and regarded with disdain by girls. As a consequence, for many years it remained an underground subculture whose members met at little advertised events and were kept informed through Animage, Newtype and other magazines that appeared at that time.

At the same time, a number of titles began to creep into mainstream popular culture, starting with the Dragon Quest role-playing game created by HoRII yûji with the specific goal of appealing to a wider audience. The game’s artwork was drawn by manga artist ToRIyAMA Akira whose anime series Dragon Ball Z premiered on Japanese TV in 1989 and became a huge national success. Then, three years later, TAKEUCHI Naoko’s Sailor Moon became an equally successful anime series, which ran until 2007, heralding the bishojo magical girl genre that until then had been considered the exclusive domain of the nerdy crowd.

Both Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon would later spearhead otaku culture’s invasion of Europe and America. However, on the home front nothing eclipsed the impact of ANNO Hideaki’s Neon Genesis Evangelion, an anime series which reworked the classic mecha (giant robot) genre in new and unexpected directions, giving more emotional depth to its characters while introducing philosophical, psychological and even religious themes. Though Evangelion’s original 26-part series only ran on TV in 1995-96, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon and contributed to giving more social exposure to the otaku community.

A key factor in Evangelion’s popularity was the commercial success of its ever-expanding line of related merchandise. Indeed, it was around this period that shop owners, publishers and other companies began to realise otaku culture’s business potential. Manga and anime fans were still seen as weird and a little scary, but they were certainly good consumers with great spending power, which seemed unaffected by the end of the bubble economy. with the number of Japanese children shrinking at an alarming rate (the country’s fertility rate had sunk to 1.57 births per woman by 1989 and would continue to fall until it hit a record low of 01.26 in 2005), the entertainment business started targeting the otaku population and their bottomless pockets.

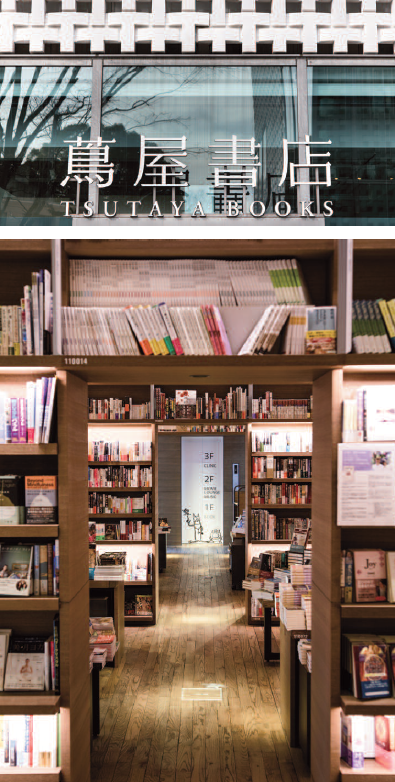

Eventually, otaku fans found their promised land in Akihabara, a Tokyo district that had been a shopping centre for radio components after the war before switching to electrical appliances, but that in the 1990s began to sell home computers. This process culminated in 1994 when computer-related sales surpassed other consumer electronics for the first time. Many computer hobbyists were also into manga, anime and video games. As a consequence, the new PC DIy era saw a gradual transformation of the area: with the release of a new generation of game consoles (Sega Saturn, PlayStation and Nintendo 64), more and more retailers started to sell game software, including manga and anime-based products.

In the second half of the 1990s, otaku culture became more mainstream with the growing popularity of idol groups and maid cafes – both highlighting and exploiting fans’ moe factor or their love for cute young girls. Formed in 1997 by singer-songwriter Tsunku, the idol group Morning Musume developed a model (later refined by the AKB48 franchise), in which the distance separating the idols and their fans was dramatically reduced. These groups, for instance, regularly appear at Handshake Conventions all over Japan where their fans can meet and chat with them and even have their picture taken with their favourite band member. Some groups went so far as to experiment with hugging and even “whisper events” (i.e. whispering sweet nothings in their fans’ ears). Idol group producers such as AKB48’s AKIMOTO Yasushi also came up with the great idea of creating “unfinished” idols whose immaturity and amateurishness attracted male fans.

Maid characters first appeared in anime in the 1980s, but definitely captured the otaku imagination in the 1990s with PC dating simulator game Welcome to Pia Carrot!!. In 1998, a temporary café was opened to promote the game’s sequel, while the first permanent maid café (Cure Maid Café) appeared in 2001. This novel idea became so successful that, according to business news website SankeiBiz, in the following decade 282 similar establishments opened in Akihabara alone. Many of them didn’t survive the intense competition, but maid cafés are still one of Akiba’s more recognisable features. In the process, they have somewhat broken out of the moe stereotype, and now many places are frequented by women, students, couples and tourists.

With anime, idols and maids appearing on primetime TV, and game consoles like Playstation becoming a common feature in most homes, the social stigma attached to otaku appeared to slowly dissipate. However, the single event that contributed most to the change in people’s attitude was the Densha Otoko (Train Man, 2004) phenomenon. This allegedly true story of a 20-something geek who falls in love with a girl originated on the 2channel message board, and spread from there like wildfire, eventually becoming a novel, a manga, a film and a TV series, all of them extremely successful, demonstrating in the process that these otaku were not so dangerous after all, and that some were actually quite cute.

In the new century, otaku culture has become almost unstoppable in its pursuit of ever new markets. During the “Akiba boom” of the mid- 2000s, the district was regularly featured in the media as a centre of a thriving subculture, and was soon followed by similar areas in other major Japanese cities like Nipponbashi (also called Den-Den Town) in osaka, and osu in Nagoya. The latter city has also become the world capital of cosplay thanks to its world Cosplay Summit, which attracts fans and contestants from around the world every year. As for idols, 2009 was the year when Akimoto organised the first AkB “election” where fans purchasing AkB CDs were given tickets to vote for their favourite girls. The results were then broadcast on television from massive arenas. Among other things, manga, anime and idols have become a powerful tool in raising Japan’s image abroad. The idol groups, for instance, have developed fan bases across Asia, with the AkB project giving birth to sister groups such as JkT48 in Jakarta, SNH48 in Shanghai, BNk48 in Bangkok and MNL48 in Manila. Nowadays, on a trip to Tokyo or other major Japanese cities it’s apparent how much otaku “sights and sounds” are part of Japanese life, from giant billboards and graffiti to the jingles in some train stations. Manga, anime and other pop culture icons are now so embedded in the Japanese psyche that comic characters are everywhere, from TV commercials and food packages to corporate logos, police mascots, and posters devoted to public safety. It really seems that otaku culture is here to stay.

GIANNI SIMONE