Benjamin Parks for Zoom Japan

In West Tokyo, there’s a new kind of market where people come to donate things they no longer need.

On a warm Sunday afternoon, I find myself outside Kunitachi Station, in Tokyo’s western suburbs. The streets are still wet, but luckily last night’s rain has been replaced by a deep blue sky, which means today’s event – the main reason I’m here today – will not be cancelled.

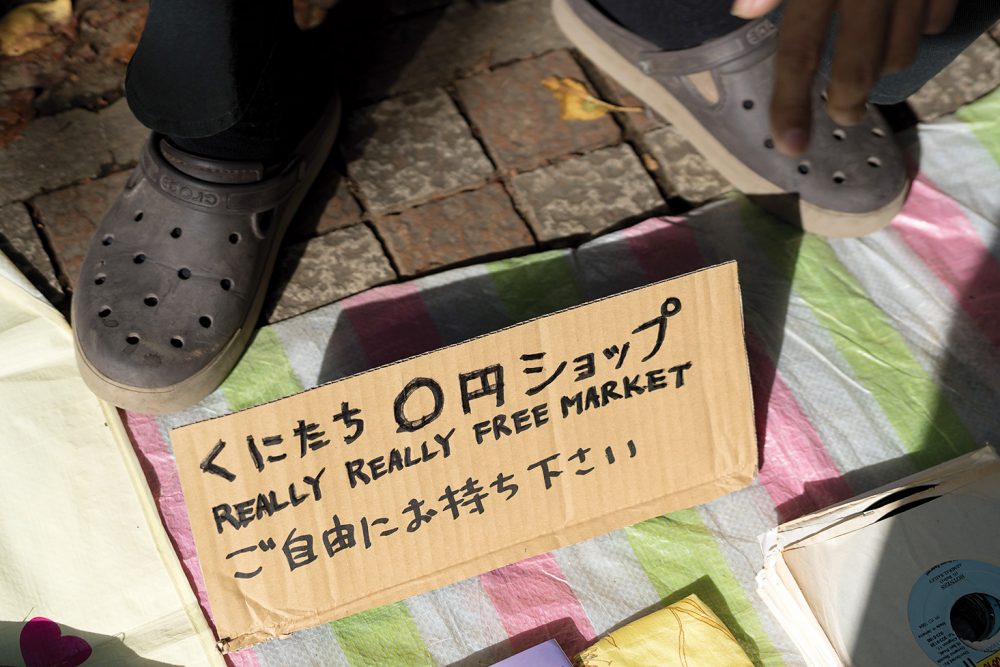

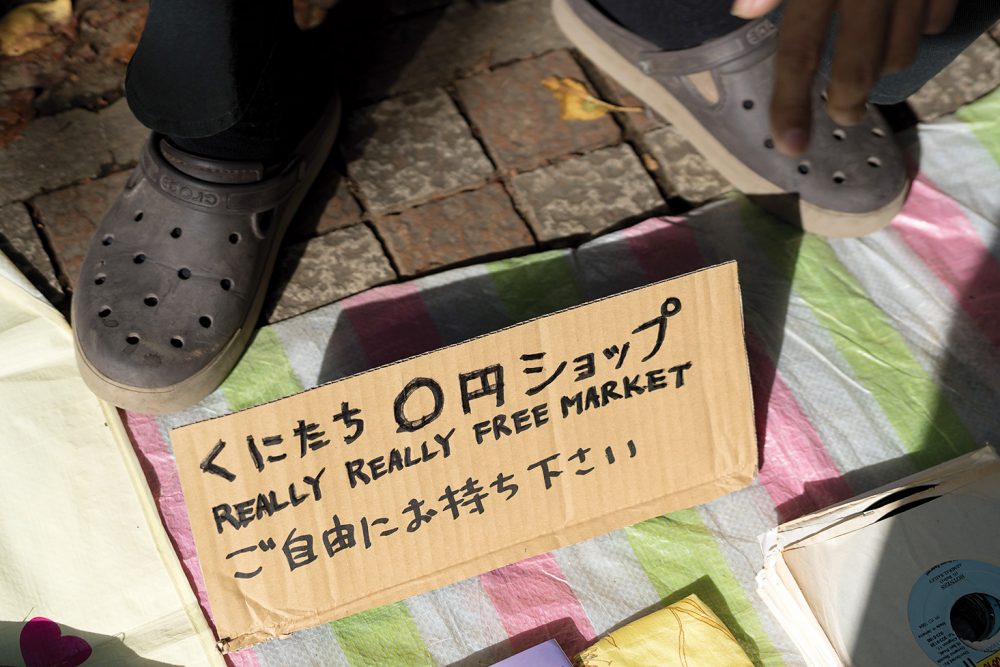

The station’s south exit opens onto a rather large square, and in its lower right-hand corner I find what I’m looking for: Kunitachi 0 yen Shop. Launched by writer and Kunitachi resident Tsurumi Wataru six years ago, this is a sort of flea market with a twist. “Every second Sunday of the month, people bring things they don’t need, display them on the street, and give them away for free to somebody who wants them,” explains Tsurumi who is the author of Post-Capitalism Manifesto, the controversial Complete Manual of Suicide and the recently-published Living with 0 Yen. “After the 2011 earthquake, there were a lot of protests, demonstrations and grassroots action taking place in Kunitachi, Koenji and other western Tokyo districts. My friends and I were already familiar with the Really, Really Free Market (RRFM), and decided to try the same thing here.”

First appearing in New Zealand in the early 2000s as a protest against a meeting on free trade, the RRFM has rapidly spread around the world as a way to oppose the capitalistic idea of a Free Market, which is actually based on consumerism and economic competition. I find it a little ironic that a free market like this is held in Kunitachi, just a five-minute walk from the main campus of Hitotsubashi University, which is not only one of Japan’s main educational institutions but the best for economic and commerce-related subjects. According to Tsurumi, there are currently about ten similar events around Japan. “Basically, you can do something like this anywhere you want,” he says. “You only need to find a nice spot with good pedestrian access where cops aren’t going to bother you. It’s not that hard if you know your town or neighbourhood. People are not really using public spaces and streets anymore. They should definitely be more active in this sense. It’s like trees and plants slowly invading the streets in abandoned cities. Creating our free space in subtle ways like this is more fun, I think. It’s a good thing for the community, isn’t it?”

The people who have gathered here today are certainly a colourful bunch, but they’re careful not to make too much noise. It turns out that besides Tsurumi and the other three or four original members, most of today’s participants are first timers. Among them there’s a housewife, a shy student, two crusty-looking guys and a loudmouthed young girl who keeps shouting to whoever cares to listen that everything is free and they can take home whatever they want. “All the things I’ve brought today are brand new,” she explains with a big grin. “You see, I’ve a weird eye problem: when I look at objects, I can’t understand how big they really are, so I often end up buying things of the wrong size.”

“I come here because I have so much stuff at home,” explains another woman. “When I change my wardrobe for the new season, I bring my old clothes here; and old books. I’d rather give them away than sell them for pennies to a second-hand chain like Book-Off. People have lots of things at home they don’t really need, so I think it’s a good idea to do this in your local community. It gives you a different perspective on your own city. It’s about ecology, too. Japanese culture traditionally encourages people to take good care of their things and try not to waste them.”

When I arrived about thirty minutes ago, the place was almost empty, but now more and more people are stopping by, attracted by the “0 yen” and “free” signs. Some of them are regulars while others have seen the market for the first time and look a little confused. “Some people don’t understand why we give away things for free,” Tsurumi says. “Someone even asked me if we were some sort of religious sect. But after six years, they’re getting used to us. We started this project in the spirit of anarchism and anti-capitalism, but you don’t have to share our ideas. Actually, most people who come by don’t care about capitalism or whatever. They only hope to find something they like. I do explain my ideas if they ask, but people are free to think whatever they want. It’s very laid-back, and I just want them to enjoy it. That’s probably why we’ve been able to keep it going for all these years.

“We end up having lots of conversations with total strangers. I’ve made so many new friends. It’s interesting how you can develop new relationships through the things you bring here. That’s a rare practice in daily life. Some people still want to give us money, but we don’t take it, of course. Others bring sweets instead. There are many kinds of people, and in the end it’s a lot of fun.”

Speaking of “different people”, at the far right of the market I find B.J. Apache, a bearded, ponytailed guy sporting a cowboy hat and black leather trousers. He shows me a picture of an old woman from Hokkaido – an Ainu shaman – and a photo of Geronimo, one of his heroes. “I encountered Ainu culture forty years ago when I first travelled to Hokkaido,” he says. “Now I own a piece of land there and I go to Hokkaido almost every year.” Among other things, Apache is displaying several small tree-like objects he’s made himself. Next to them, there’s a flyer about Ainu-related issues. Apache explains that years ago a group of researchers from the University of Tokyo and other academics dug out bones from an Ainu cemetery, and now members of the Ainu community and other sympathisers are trying to get the bones back.

Sitting next to Apache is a tall long-haired guy completely dressed in black leather – he’s giving away a bunch of old rock 45s. To my surprise, he tells me he is “Soundman” Mitamura, the 46- year-old guitarist of historic punk band Deepcount. The term “punk” actually fits better with the band’s attitude and political stance than their musical style – an elegant and complex mix of rock, funk and dub reggae, which serves as a backdrop for vocalist Kuwabara Nobutaka’s spoken word declamations. I learn from Soundman that at the end of the month they are playing at Kakekomitei, an infoshop-cum-barcum- event space near Yaho Station, just south of Kunitachi.

Back at Tsurumi’s spot, I ask him what message he wants to convey with the 0 yen Shop. “For me it’s a street event and an anti-capitalistic action,” he says. “It’s ridiculous to keep producing new stuff and throwing away things that are still perfectly good. I want these things to stop. Instead of making a fuss about buying and selling, we should just give away what we don’t need. Hopefully somebody else wants it.

“I believe we have the power to resist capitalism, and I have a feeling that many other people like the idea of replacing money transactions and endless consumption. So many people become unhappy because of money. I don’t like how money rules our lives. I’m also very sceptical about corporate power. Why are these companies so strong? You’re considered a loser if you don’t work for a big corporation and don’t earn lots of money.

I hate that. Of course you’re free to look at life any way you want, but I prefer a society with different values.”

Tsurumi often travels to Southeast Asia, where he checks out the local markets and has many friends and contacts there. “The big companies are invading those places too,” he says, “and I’m afraid all those small family-run shops and street vendors will disappear. But for now, they still seem to be thriving.

“It’s really sad when you consider what happened in Japan. Some time ago, I saw a 50-year-old map of Kunitachi. At that time there were many small shops around my house, but they’ve all gone; now there’s just one big store at the station. Business should be a part of the local community, not a destructive factor.”

I find a copy of Francois Lelord’s Hector and the Search for Happiness among the things Tsurumi is giving away, so I ask what happiness means to him. He thinks about it for thirty seconds looking into the distance, then he shows me all the happy-looking people who’ve gathered today: “It’s being with your friends, like now, sharing a good time and doing what you like,” he finally says.

J. D.