Hajime is the first work to be published by the ToCo collective, in which artists recall their first impressions of the Japanese capital.

Unity is strength. By embracing this old adage, artists have joined together to produce high-quality zines.

Koenji is a nice, quiet place in the Tokyo suburbs, but if you had ventured along one of its narrow backstreets at the end of October, you would have noticed a lot of people cramming into the small Clouds Art + Coffee gallery-cum-café and spilling out into the street. They were there for the second edition of Zine House, a two-week zine exhibition. The event featured some fifty zine makers (including a few foreign authors).

Nowadays, everybody is familiar with blogs, though relatively few people know that a long time before the Internet, there was (and still is) a whole community of independent publishers who more or less did the same thing bloggers do today, but on paper. Zinedom is a mostly underground world that usually flies under the radar of the mainstream media. However, zinemaking is a global phenomenon with thousands of practitioners. Try a simple online search for “zines” and you will end up with millions of hits.

The Japanese zine scene may not be as big and lively as in other countries, but there are several events, stores and so-called “infoshops” in Tokyo where you can find these small-scale publications, including Mount Zine, Utrecht (Omotesando), Irregular Rhythm Asylum (Shinjuku) and historic underground bookstore Taco Ché (Nakano). Even Tsutaya’s Daikan’yama branch has a small corner devoted to this medium.

Three of the participants in the Koenji event (Erica Ward, Julia Nascimento and Felipe Kolb Bernardes) are also members of ToCo (short for Tokyo Collective), a newly-launched group of creators (artists, illustrators, writers, and mangaka) who in the space of a few months have already made two interesting zines. I had a chance to meet them at the event they organised to celebrate the publication of their second work.

Erica, how did you end up in Japan?

Erica Ward : After a short culture visit to Japan in high school, I went on to study Japanese at the University of Massachusetts and always knew I wanted to come back. I finally moved to Japan in 2010, working in English education while doing art on the side. I was up on the northeast coast for three years, then down in the countryside of Osaka, before getting a chance to move to Tokyo, where I finally took the leap into doing art full time. I’m very inspired and influenced by Japan, and most of my current work features Japanese imagery in a sort of poprealism style. The different regions of Japan have all had an effect on my art as well, and now that I’m in Tokyo, I’m noticing a strange urge to draw all the details and unnatural straight lines of cityscapes. This is actually a main theme in my story in hajime.

How’s your life in Japan now?

E. W. : Apart from being a visual artist and freelance illustrator, I do some freelance writing, translating, volunteering at a cat rescue centre, and other odd jobs as they come up, which has truly been one of the perks of the freelance lifestyle. Tokyo has given me so many opportunities to showcase my artwork—art festivals, galleries, competitions—but it’s also been an incredible place to meet interesting people and learn new things in general.

Speaking of meeting interesting people, how was ToCo born?

Julia Nascimento : Last year Felipe and I took part in Comic Art Tokyo and the Tokyo International Comic Festival (see Zoom Japan #53), and we were mesmerized by all these international creators. We immediately began to think about creating a group that would meet regularly, not just once a year like those festivals. At the same time, Erica wanted to make a zine, so at the beginning of this year, we reached out to a handful of Tokyo artist friends, got together and compared ideas. We all agreed that working on a common theme, setting some deadlines and being committed to working with others on a joint artistic project would give us that extra push and motivation to create fresh work.

E. W. : I’ve loved drawing since I was a kid, and looking back, I realise I’d made magazines and comics from a young age. So maybe working on zines now just brings me full circle. I’d say our zine was born out of two factors: my own personal hope that starting a structured project would force me to stretch my creativity and spark productivity, and a feeling that it would be “mottainai” (Japanese for “a waste of a good thing”) not to work together with some of the amazing artists I’ve met since moving to Tokyo. Also, a zine would give us all a satisfying finished product, but also be informal enough to encourage experimentation.

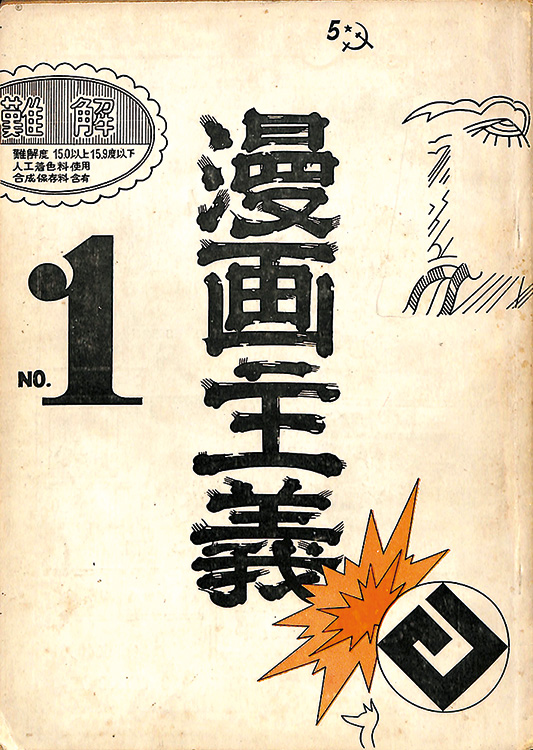

J. N.: I had an idea that zines had to be politicized and militant, even subversive. But when Felipe and I arrived in Tokyo and checked out the local scene we found introspective, informative, artistic and funny zines.

Tell me about The Tokyo Collective.

E. W. : While gathering all the works for our first zine we decided to push ourselves a step forward and create a group. Though we could have just made a single zine as a one-time project, there was something exciting about creating an identity and stirring up the expectation of more zines to come. So, we set up ToCo. We’re always looking forward to adding more members to our collective. We had a fantastic opportunity to hold an exhibition of the original artwork from the two zines and this encouraged us to do even more.

Your first work is called hajime which means “beginning” or “start” in Japanese. How did you come up with the title?

E. W. : We decided that the first theme would be “First impressions of Tokyo”, since the original group of us were not Tokyo natives. In the end, Hajime grew to include submissions from seven artists. The final collection is seven free-style four-page works of artists’ memories and feelings about their first days in Tokyo. We felt that “beginning” fitted both our theme and our budding zine collective.

Both your zines look beautiful and have great production values.

E. W. : My original idea was to make a classic cheap staple-at-home zine, but when Julia jumped onboard and joined me as co-producer, she suggested we made a splash-worthy project out of the idea. Then we grew in number and decided to print a larger number of copies. So we chose to go with a printer. We actually had all the artists submit their work to us digitally, so some was scanned and some was created completely digitally. ]

J. N. : Japan is a little ahead in printing compared to other countries. Because so many people make zines, especially the dojinshi (self-published) versions, you can find many printers who are fast and relatively cheap and offer competitive packages if you make a lot of copies. We printed 300 copies of Hajime and 400 of Monogatari, which has 14 contributors.

INTERVIEW BY GIANNI SIMONE