Yoshiki considers himself to be the spokesperson of Turtle Island rather than its leader.

A good example of creativity used to help others, every year Turtle Island organises a unique kind of music festival.

Few bands in Japan are as exciting as Turtle Island. Formed in 1999 in Toyota, near Nagoya, this “punk orchestra” fuses traditional Japanese carnival beats and melodies with distorted guitar riffs and an array of musical instruments from India, Korea and Africa. Since 2011, they have organised the Hashi no Shita Ongaku-sai (Under the Bridge Music Festival) in Toyota, a three-day extravaganza which looks and feels more like a chaotic traditional festival than a music event, and is a unique opportunity to see some of the best Asian bands in action. Zoom Japan talked with Yoshiki, the band’s charismatic vocalist and lyricist, about their influences and DIY philosophy.

What is this place where you are now?

Yoshiki : This is our community space. It’s called the Hashi no Shita Centre, like our annual festival. We make and teach art and music, as well as fashion and product design, and hold a number of events.

You are known among your fans as Japan’s Joe Strummer [the late vocalist of The Clash].

Y. : No way (laughs)! I like and respect him very much for what he did, so I’m glad about the comparison, but they’re just being kind.

You’ve played in different bands and even have a solo career, but you’re most famous for being Turtle Island’s frontman. How was the band born?

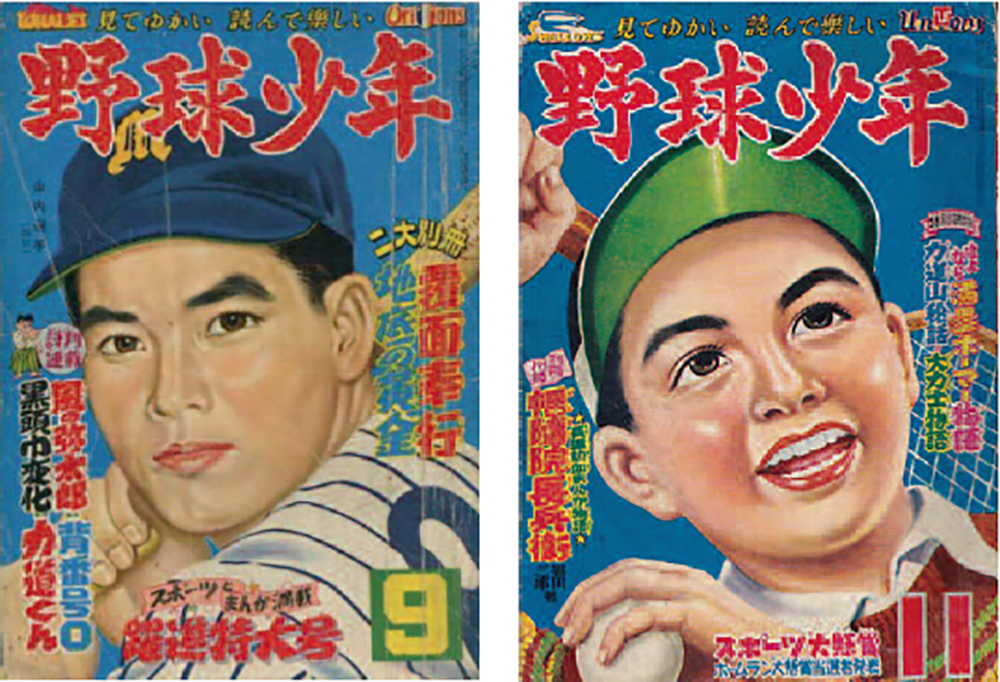

Y. : I started singing in junior high and played in a number of local bands that were heavily influenced by English hardcore punk. We even toured the UK. But then we realised that our social and cultural environment had little to do with England. Moreover, we had a different musical DNA. So we decided to make a new kind of music, which mixed punk’s urgency and raw energy with Japan’s and Asia’s musical heritage. That’s how we began to add Asian beats and melodies to our songs, and to play Asian instruments such as taepyeongso, taiko, bamboo flute, gong, morin khuur, etc. After all, I have Korean roots…

What do you mean?

Y. : I was born in Japan, but I’m actually a Zainichi Korean i.e. an ethnic Korean with permanent residency status in Japan. Since I was born, I’ve been exposed to this double cultural heritage – Japanese and Korean – so for me it’s natural to mix these two musical traditions.

I know that life for Zainichi in Japan has been hard, especially in the past.

Y. : Certainly my father’s life has been hard because Koreans faced a lot of discrimination when he was younger. However, I’m a thirdgeneration Zainichi and grew up in the 1980s, so I haven’t felt it as much as my father. At home we were a typically Korean family with strong Korean values and customs, but my parents let me go to a Japanese school, and I grew up with lots of Japanese friends. In the end, I feel lucky because I was able to enjoy both cultures and was able to apply this aspect of my MUSIC rock’n’roll attitude A good example of creativity used to help others, every year Turtle Island organises a unique kind of music festival. life to my music. I consider Turtle Island as a sort of cultural bridge between Japan and Asia.

Do you sometimes go back to Korea?

Y. : Once a year, we visit our family grave. Turtle Island has never played in Korea, but I sometimes do a few acoustic sets there. It’s funny because people always talk about discrimination in Japan, but Zainichi are discriminated against in Korea too.

Back to Turtle Island, more than a band it looks like a punk orchestra. You have quite a big lineup.

Y. : You’re right. We started with about 13-15 members. At one point, we had as many as 18, though now there are “only” nine of us left. Especially in the beginning, we were all childhood friends who had grown up in the same neighbourhood, gone to the same schools, played together every day. It’s always been a very tight bunch of friends.

Even though you’re considered the band leader.

Y. : I don’t think that’s the right word. I write all the lyrics, but we all contribute to the music. Each one of us has a different background, different musical tastes, and everybody is welcome to come up with a melody or song idea, which we then develop collectively. So more than the leader, you could say I’m the frontman and spokesperson.

It must be hard to keep such a big band going, even financially.

Y. : In fact, right now, out of the current nine members, only three are able to make a living out of music – music and other creative activities. Three others are part-time musicians and do a variety of jobs on the side, and the remaining three work at Toyota Motors or have an office job.

Quite surprisingly, your annual music festival in Toyota is free. How do you manage to keep it going year after year?

Y. :Hashi no Shita was born in 2011 after the triple disaster in Fukushima. Like many other people, we went up to Tohoku to help, and joined many antinuclear street demonstrations. However, we reached a point when we thought that instead of simply complaining against the government, it was better to do something more constructive. So we created this music festival in the space under the bridge where we’d first gathered to play. From the start, we didn’t want to charge a lot of money. But, of course, organising such an event takes a lot of money. So to be precise, the festival is not completely free, but nagesen, i.e. everybody is free to pay – to donate – whatever they want, whatever they feel is right. If you have no money, even 500 yen is okay, and maybe you can help with clearing up at the end. For us, there’s no difference between the bands on stage and the audience. We’re all part of the same DIY community, and you’re free to help and contribute in anyway you want. That’s why it’s called ongaku-sai: more than a typical musical festival like Fuji Rock or Summer Sonic, our event is closer to a matsuri, i.e. a traditional local festival where the whole neighbourhood is involved. Fuji Rock is a business. We don’t do it for the money.

Is that why according to many fans Hashi no Shita is a special, one-of-a-kind event?

Y. : I think so. This is not just a musical festival where a bunch of bands get on stage, do their thing and then go home. The matsuri itself lasts for three days, but two to three weeks before the start we gather all kinds of scrap material from construction companies and build a sort of junk village. We even make a wooden cart, the kind you often see at traditional matsuri around Japan. Content-wise, it’s a place where different cultures and lifestyles meet and where people are free to try new things. For us, in a sense, it’s a sort of experiment. There’s a great deal of improvisation going on, and we offer no clear-cut messages, answers or solutions. You have to find your own way.

Even your lyrics don’t seem to be overtly political.

Y. : I never write openly political songs. Obviously, we have our opinions about society and politics, but I prefer to sing about life, about what being human means. Everything is connected, of course, but I believe that right now in Japan, rather than shouting slogans we need to talk about more fundamental issues that go beyond ideology. People have to decide what they want to do with their lives.

I know you even have your own source of electricity.

Y. : Yes, this is the only festival in Japan that’s run on 100% pure solar power. The system was designed by Personal Energy Kobe Japan, with whom we have been collaborating for many years now, and it provides all the electricity for the festival site from the stage PA system to the food court area. They are a sort of additional band member: guitar, bass, drums, electricity (laughs).

What is DIY for you?

Y. : As I said, my point of entry into the DIY community was through hardcore punk, so obviously indie music has always been my main reference. But regardless of what you do – be it music, art or zines – the single unifying thing is to be independently-minded and find your autonomous place in the world without passively following what mainstream society tells you to do. When we first started Hashi no Shita, seven years ago, it was a small project and we didn’t really know what we were doing, but since then the city around us has slowly changed. More and more people have been inspired to start new things, to be creative and think more freely. If we can do something like Hashi no Shita, everybody can do it. In the end, the DIY ethic is not about doing something exceptional or starting a revolution. It’s about experimenting and finding alternative ways of life.

INTERVIEW BY J. D.