![No65 [STRATEGY] Sake, an influential factor](https://www.zoomjapan.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/65_04.jpg)

After manga, animation and cuisine, sake is an essential element of Japanese soft power.

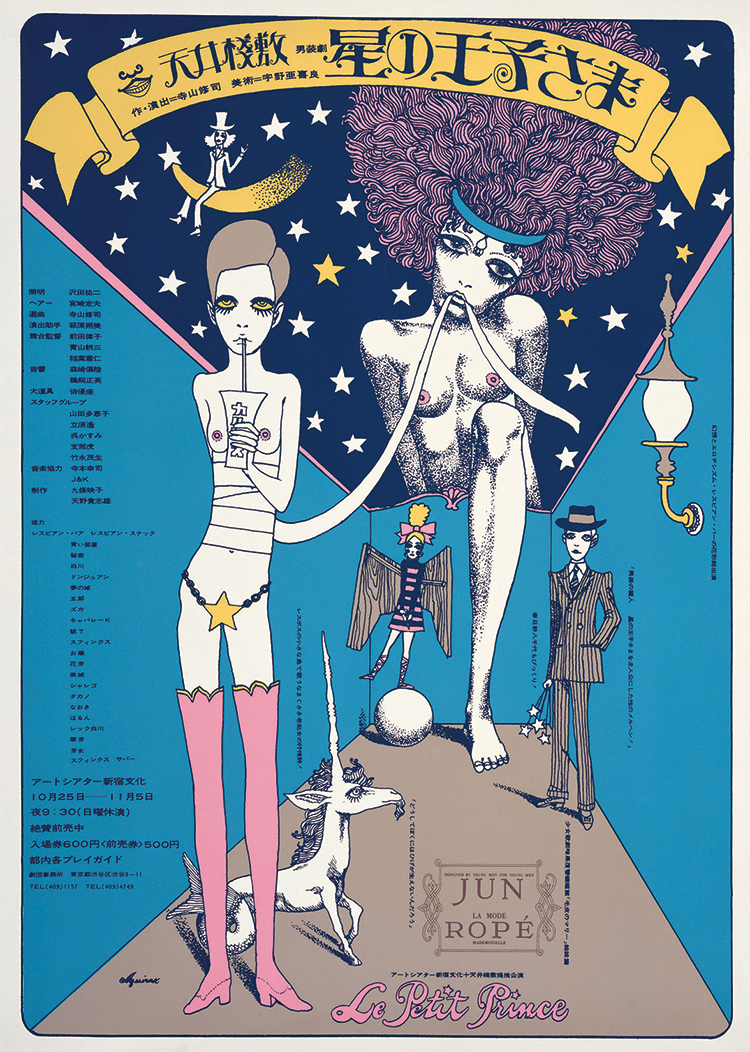

Since the end of the Cold War at the turn of the 1990s, Japan has been searching for its place in the world. After living in the shadow of the United States, which had assured its security and allowed it to develop economically, the Land of the Rising Sun found it was obliged to take on new responsibilities. What had often been portrayed as a political dwarf now needed to make itself heard on the international scene. To succeed, it needed both the time and the means. In an ever-changing environment, particularly with the rise of Chinese power in Asia, there were several beneficial factors in Japan’s favour, thanks to its being viewed with benevolence around the world. In contrast to other countries, which depend on their military strength — hard power — to assert themselves, it was able to rely on its culture, or soft power, to improve its image in the world. Manga and animated film became ambassadors for Japan even if, to begin with, it was not deliberate government policy to help the spread of popular culture. It wasn’t until the start of the 21st century that the Japanese authorities realised their importance and established the strategy of Cool Japan.

They rapidly sought to enlarge popular culture’s field of influence. After manga, cuisine (washoku) was targeted by the government. The enthusiasm of foreigners for Japanese food was an opportunity to promote national agricultural production at a time when it was in need of a great deal of improvement. Furthermore, the necessity to clearly distinguish “real” Japanese restaurants from “false” ones — of which there were many — led the government to introduce a system of labelling to ensure quality. The fashion for Japanese food, we must remember, started in North America with American consumers’ enthusiasm for sushi in 1980s and 1990s. By achieving Unesco World Heritage status for washoku in 2013, Japanese authorities in a way succeeded in completing the circle.

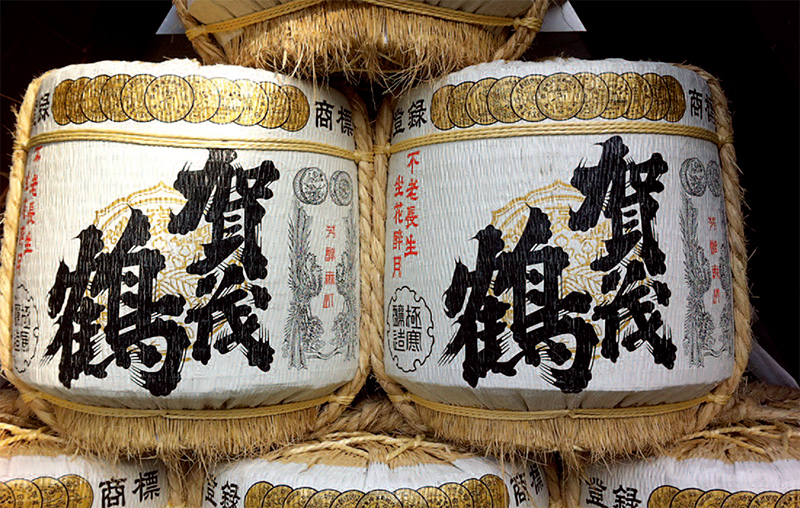

That’s the reason they began to promote sake worldwide. It not only meant they were able to find new markets for a product that had been in rapid decline over the past few decades, but it also gave them a new and not insignificant way of wielding influence. After missing the boat in the case of whisky, which didn’t need any help from the government to gain worldwide popularity, it was essential to find an alternative. You couldn’t imagine anything better than nihonshu in so far as it symbolizes the essence of Japanese ancestral culture. If you know the extent to which wine represents a means of influence for France, then you’ll now understand why the Japanese government made sake a priority. This strategy is not confined to France, but coinciding with the launch of a new brand of sake, its aim is to encompass the world. In mid-September, the Japanese embassy in India organised a nihonshu tasting in New Delhi for the second year running. As the Times of India journalist present at the event explained, this one was even more important than the one held in 2017. “Its promotion in India is congruent with efforts to boost Japan’s presence in India’s mindscape,” he adds. Today, India is one of Japan’s most important allies in Asia in the face of Chinese ambitions. So it’s essential to improve the country’s image, and sake is very useful in as much as it is “the entry point for understanding Japanese culture” according to the Indian journalist. From Singapore and Melbourne, Australia, in June to San Francisco, in September, the world was able to experience the atmosphere of sake bars when Japanese producers came to promote their sake and contribute to their country’s good image.

Just as manga saw the emergence of a generation of foreign authors capable of producing work inspired by this Japanese form of expression, such as Frenchman Tony Valente (see Zoom Japan no. 63, July/August 2018), sake generates careers beyond Japan’s borders. This desire to imitate represents the extent to which Japanese culture has become part of our daily lives. Though India hasn’t yet started to produce sake, there are many who are doing so in Europe. From Norway, where a brewer of local beer, None O, started to produce sake in 2010, to Spain with its Kensho Sake available since 2015, you can find a growing number of producers. In France, in 2016, Hervé Durand created Kura de Bourgogne in Vendenesse-les-Charolles, in Saôneet- Loire. It’s a brewery and a factory producing Japanese condiments “in the Burgundian tradition”, as it states on its website. You can also give the example of Great Britain with the Dojima Sake Brewery situated in an 18th century manor house near Cambridge (see Zoom Japan, no. 64, September 2018), or even Kanpai in London, where the catchphrase is “Japanese traditions, London style”. There’s no doubt that nihonshu represents a not-insignificant ingredient in Japan’s strategy to increase its influence.

Odaira Namihei