![No65 [FOCUS] Japan according to Takahashi Gen’ichiro](https://www.zoomjapan.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/65_03.jpg)

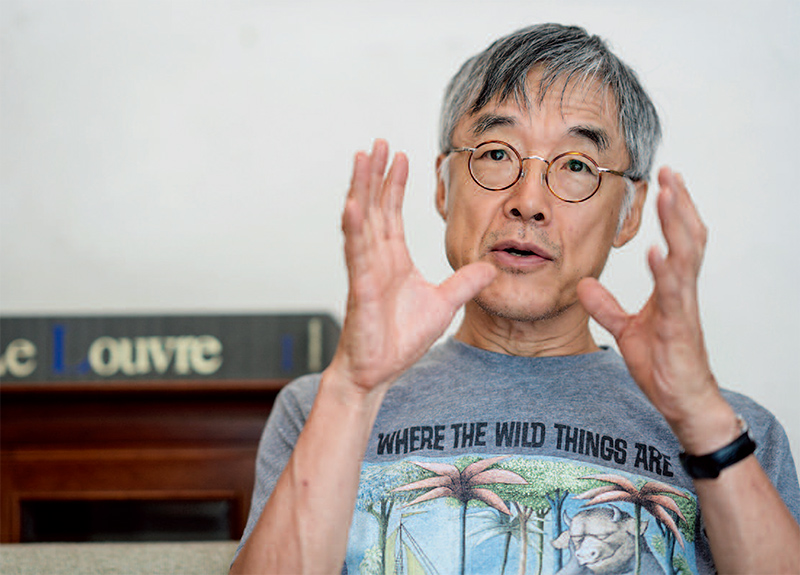

The writer, who is considered to be one of the finest novelists in the archipelago, shared his thoughts with us.

Takahashi Gen’Ichiro is one of the most important all-round Japanese writers of the last 40 years, and one of the pioneers of the post-modern novel in this country. From fiction to essays, from literary criticism to sports writing and political commentary, the 67-yearold Takahashi mixes a strong moral stance with an extraordinary imagination (he has been compared to Thomas Pynchon and Italo Calvino), which constantly challenges the reader to abandon rationality in order to explore the worlds he creates.

Takahashi’s life is almost as picaresque as his stories. Born in Hiroshima Prefecture, he entered Yokohama National University, but got involved in the student movement and never finished college. As a radical student, he was arrested and his ten-month experience in prison left him suffering from a form of aphasia for many years. He spent the next ten years working in construction, until his doctor suggested he tried his hand at fiction as a form of rehabilitation.

His breakthrough arrived in 1981, when his gonzo-like debut work, Sayonara, Gangsters, won a prize and took the literary world by storm. Displaying a great love for American culture and a penchant for both parody and pastiche, Takahashi is not afraid of mixing highbrow literature, pop culture and pornography – most notably in Jon Renon tai Kaseijin (John Lennon vs. the Martians) – in his quest to create new fictional worlds.

For many years, Takahashi has taught at Meiji Gakuin University, while contributing articles on literary and social criticism to a national daily and writing a popular column about horse racing, one of his passions.

For this interview, Takahashi invited me to Kamakura, the seaside town 40 km south of Tokyo where he has lived for many years. Finally free from his teaching duties and enjoying the

You are currently serialising your new novel, Hirohito, in Shincho magazine.

TAkAHASHIGen’ichiro:Yes, I’ve just got started, so I guess it will take about five years to complete. Right now, each new instalment is coming out only once every two months. However, next year I’ll have more time to devote to my writing as I’m quitting my university job, so I’ll be able to deliver a new chapter every month.

Your book is a historical novel based on the real-life encounter between the Japanese Emperor and scientist Minakata kumagusu in June 1929.

T.G.: It’s actually part of a larger Japanese historyrelated project. In the last 15 years, I’ve worked on a series of historical fiction. In 2004, for example, I published a sort of historical pastiche, Nihon Bungaku Seisuishi (History of the Rise and Fall of Japanese Literature), which was set during the Meiji period (1868-1912). In this novel, I mixed the lives of famous modern writers such as Natsume Soseki, Mori Ogai and Ishikawa Takuboku (when they were still struggling to change Japanese literature) together with the High Treason Incident, the 1910 socialist-anarchist plot to assassinate Emperor Meiji. This was arguably the most important political event of the early 20th century, not least because the police used mainly circumstantial evidence as a pretext to suppress left-wing dissidence. In the end, 26 people were sentenced to death, and 12 of them were actually executed, including anarchist leader Kotoku Shusui and feminist journalist Kanno Sugako. Next, I wanted to tackle the Taisho period (1912-1926), but didn’t have any good ideas, so I put this project aside and worked instead on a monthly series of opinion pieces for the Asahi Shinbun newspaper. However, two years ago the current Emperor, Akihito, declared his intention to abdicate in favour of his eldest son. This made me think about his father Hirohito, and the role both have played in the last 100 years of Japanese history. So I decided to devote my next historical novel to Emperor Showa (as Hirohito is officially called).

But why did you choose this rather obscure episode in Hirohito’s life? I must confess I didn’t really know anything about it.

T.G.:As it’s a work of fiction, I needed to create a dialogue between two characters in order to make the story more compelling and dynamic. Now, Minakata may not be very famous, especially abroad, but he was a unique intellectual and a very unusual person, particularly considering the overall character of Showa-period Japanese society. After dropping out of the prestigious University of Tokyo (because he felt he couldn’t learn anything in that academic environment), he went to America to study fungi, especially slime moulds. Then he travelled to Cuba and around Latin America with a circus, and finally arrived in England where he contributed many articles to Nature magazine, establishing himself as a top naturalist and biologist. Even after returning to Japan, in 1900, he resisted Tokyo’s pull and went back to his native Wakayama Prefecture where he eventually settled down in Tanabe. So, as you can see he was a very atypical Japanese person.

And then he met the Emperor – an extraordinary thing in itself.

T.G.: You can certainly say that. On one hand, there’s Hirohito, who at the time was still venerated as a demigod and was as remote as a human being could be. On the other hand, there’s Minakata, who was not only one of a kind; he had an anti-establishment streak too. In 1910, for example, he was arrested for protesting against the government’s attempt to consolidate and merge all local Shinto shrines (he argued that it would hinder community life, ruin historical buildings, and damage the natural environment surrounding the shrines). Also, he was briefly connected to the High Treason Incident, even though he had nothing to do with the Wakayama cell of terrorists.

However, though so different in many respects, Minakata and Hirohito were united by their love of science. In fact, the Emperor himself was an accomplished botanist who specialised in the study of hydroids – a rather obscure subject – but was interested in slime moulds as well. That’s why Hirohito expressed his desire to be taught about slime moulds by Minakata. Minakata, quite incredibly, agreed to this, but added that he wasn’t very keen on leaving his beloved Tanabe. Think about that: his refusal to go to Tokyo could almost be considered an act of treason. But Hirohito was unfazed and said he would travel to Tanabe instead.

How have readers reacted to Hirohito so far? I’m asking because the Emperor is a very delicate subject in Japan, and whoever talks or writes about the Imperial Family runs a serious risk of being verbally and sometimes even physically attacked by far-right wingers.

T.G.: For the time being, everything seems to be okay, not least because nobody really reads literary magazines. Maybe there’ll be a stronger reaction when the novel comes out in book form, but I doubt it. For one thing, though this is an interesting episode in Hirohito’s life, it’s not particularly controversial. Anyway, today’s right wingers are not as dangerous or bellicose as they used to be. Besides, they don’t even like the Emperor that much now, especially after Hirohito and his son Akihito embraced liberalism – well, of a kind. Everybody knows that after the war, Hirohito refused to visit Yasukuni Shrine (the Japanese equivalent of Arlington National Cemetery) after it was revealed that 14 Class-A war criminals had secretly been enshrined there. But not many people know that, in the 1970s, Hirohito even thought about converting to Christianity. It’s as if Donald Trump wanted to become a Muslim (laughs)!

Have your publishers or editors ever suggested you change subjects or tone down your stories and essays?

T.G.: No, not really. As far as I can remember, only when I wrote Koi suru genpatsu (A Nuclear Reactor in Love), did my editor initially balk at my idea of mixing soft porn and the nuclear disaster in Fukushima (laughs). You see, the biggest problem now is online trolling, where all those intolerant bigots are free to anonymously criticise everyone and everything with impunity. But most of those people don’t read books anyway – at least, not my books. They usually focus their hatred on TV shows and other people’s blogs or websites. In fact, the biggest source of problems for me has been Twitter. I remember, I was labelled a traitor once, and even got death threats for a comment on Japan’s foreign policy.

Even the earthquake that hit Osaka on 18th June 2018 led to a slew of hate speech tweets warning of “crimes” committed by foreign residents. Unfortunately, this has become a familiar postdisaster trend on the internet. Do you think the Japanese are racist?

T.G.:Discrimination and prejudice are an unavoidable part of society, so I can’t really deny the existence of racist people in Japan. It’s probably also true that the Japanese, for a number of reasons, have an underlying fear of “the other”. On the other hand, most people in this country have (or used to have) enough common sense to stop or curb discriminatory treatment. This is something we learn from childhood. The real problem, in my opinion, is that the traditional parent-child relationship is gradually growing weaker, as young people find refuge and make connections online. Unfortunately, the internet has become a place where people’s anger and frustrations get magnified, and those who try to stop this kind of verbal abuse – what we could call the voice of reason – are easily overwhelmed and silenced. What I’m trying to say is, I don’t think that moral principles in Japanese society have deteriorated. Rather, new means of communication and connecting, such as social networks, have helped spread those negative messages and ideas that were already out there, but, in the past, were confined to smaller groups of people.

Years ago, Umberto Eco famously said that the internet had given all morons the right to freely express their opinions. Do you share his negative point of view?

T.G.: Yes and no, because, after all, that’s what democracy is all about: the right to say what you think, regardless of your IQ or political views. Take literature, for example. Writing used to be an elitist pursuit, and only a relatively small group of people was given the chance to publish their works. To start with, you had to be a skilled writer. Then you had to be lucky enough to find a publisher who was ready to take a gamble on your work. But with the internet, everybody can be an author, and everybody can read many things for free. This is direct democracy in its purest form. How can you not love something like that?! Then again, even in ancient Greece, the cradle of direct democracy, people would be shouted down if they said something particularly stupid. In other words, there must always be a device, a method to regulate democratic dialogue and limit any abuses, so that the whole system is able to work smoothly. Obviously, it’s difficult to strike a balance between freedoms and limits, but I guess that’s the only way to make it work.

Speaking of freedom and good manners, there seems to be an increased intolerance on trains and subways in Japan towards pregnant women, people with disabilities, and parents with children – especially if they’re using a pushchair – on the part of tired, stressed out commuters.

T.G.: It’s truly unbelievable, shameful behaviour. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen someone refusing to give up their seat to a pregnant woman or an elderly person.That’s plain selfishness, and in my opinion, it’s the result of our increasingly competitive society. It starts with the education system, which pushes kids to fight for a place in an elite school. Most juku (crammers) adopt this cut-throat approach. One develops tunnel vision and ends up seeing only the goal at the expense of everything else. Life becomes an obstacle race, and the people around us become a nuisance or even an enemy to fight. I’d say there’s a lack of empathy towards people we don’t know, people who are outside our circle of family and friends. Also, one more thing at play in such situations is a negative version of “groupism”. The Japanese are famous for doing everything together, as a group. Nobody wants to stick out and do something different from the majority. On a train, you can actually see people looking around to check what others are doing. Everybody pretends not to see the old lady standing, and they probably think, okay, if nobody moves, why should I give up my seat?

Do you think the Japanese are conformists?

T.G.: I think so. At least the system is such that it turns them into conformists. Kindergarten and elementary school children are very active and creative, and probably Japanese mothers are less strict, more forgiving, when compared to Western parents. However, starting from the end of elementary school, these kids are slowly moulded into uniform products. It’s not by chance, I think, that from junior high school they start wearing a uniform. Rules become stricter, and people are encouraged to think and act as a group. I don’t know why, but the Japanese definitely don’t seem to like individuality.

Earlier, we talked about moral values. Last March you “translated” into modern Japanese the 1890 Imperial Rescript on Education, which, until 1948, was meant to be a guide to education and public morality, and had to be memorised by all students. Why did you do that?

T.G.: I got a lot of flak for that (laughs). Actually, that’s not my only modern Japanese version of an old text. I like to see what the classics say about contemporary Japan, and how something written two- or three-hundred years ago applies to our society. The Imperial Rescript on Education caught my attention because, for one thing, everybody was talking about it as the current conservative government seems to be espousing some of its values. Then in 2017, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and his wife Akie were involved in a big scandal when it was revealed that they had helped an ultra-nationalist private school buy a parcel of governmentowned real estate at a fraction of its estimated value. The financial issue aside, the most worrying thing was that the school’s curriculum included reciting the Rescript daily, like in the “good old days”. So I thought, everybody is talking about this document, but do we really know it? Do we actually know what it says and why it’s been so controversial? So I read it (it’s actually quite short), but I didn’t really understand it because it’s written in the kind of highly formal, esoteric language used by the Emperor in the 19th century. Then I tried again, this time with the aid of a dictionary, and rewrote it in a way that could be easily understood by everybody. Now, when you tackle these old documents, you always have to keep in mind the context in which they were written. In the Rescript’s case, it was a time when the government was pushing for an “emperor-centred” society. The ruling elite created a social contract based on a bond between a benevolent ruler and his loyal subjects – who were required to sacrifice their lives for the State, should an emergency (i.e. a war) arise. That’s probably the most controversial point because Abe is currently trying to change the pacifist Constitution in order to remilitarise the country.

So I guess you had this connection in mind when you translated the Rescript?

T.G.:Yes, of course. You can’t really understand the present if you don’t know the past. That’s the main motivation for writing Hirohito, too. At the most basic level, I want to show that 50 or 100 years ago, Japan was experiencing the same kind of situation we’re in now. We made some big mistakes then, and we must be careful not to repeat them. As they say, those who forget history are bound to repeat it.

As you have mentioned Hirohito again, I’d like to ask you about the Imperial system. Until 2004, for instance, the Japanese Communist Party was absolutely opposed to the existence of the Imperial House. Even now, despite adopting a more lenient approach to this issue, they support the establishment of a democratic republic. On the other hand, the current Emperor (who, by the way, plans to abdicate next year) and the Imperial Family as a whole seem to be hugely popular in Japan. What’s your opinion on this matter?

T.G.: The big issue for me is that the Imperial system and the Constitution don’t fit well together.

In what sense?

T.G.: This is a complex matter and requires a long explanation, so please bear with me. First of all, the Constitution isn’t really clear on what the Emperor is supposed to do. Some of his duties are clearly stated in the document, but there are a couple of important functions that are not: performing religious rites inside the Imperial Palace, and travelling around the country and the world to comfort the spirits of the dead (which means, especially for Akihito, to apologise for the Japanese army’s appalling actions during the war). They are quite demanding jobs, and Akihito – who is 84 – thinks he can no longer perform them. That’s why he wants to step down in 2019.

To me, though, there’s another point that’s even more controversial. On the one hand, according to the Constitution, the Emperor is the symbol of the Japanese nation. However, on the other hand, all those human rights that are generally guaranteed by the Constitution are denied to him. In other words, he’s not free to speak his mind, can’t choose a job, and isn’t really free to marry whoever he wants. To me this situation is quite strange. I even posed the same question to the leading expert on constitutional matters, who happens to be a friend, and he admitted it was a thorny issue. Now, given these conditions, I believe the best solution is to revert to the pre- Meiji era situation: turn the Imperial House into a sort of religious organisation, and move the Imperial Palace back to Kyoto. This way, we can separate State and religion, and turn the Constitution into a truly secular set of principles.

Last but not least, I can’t understand why the current political elite is opposed to female succession to the throne. Not only, according to the polls, are most people eager to see a woman ascending to the throne, but in the past, we had eight empresses, the last one abdicating in 1771. Besides, according to Japanese mythology, the emperors are considered to be direct descendants of Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun. You see?

I mean, even Shinto’s main deity is female! In fact, this supposedly men-only tradition is only some 150 years old. This takes us back to what I said about our duty to know the past because there are many instances when the people in power seem to act with complete disregard for the past.

How about the Constitution? Do you think it should be amended?

T.G.: As you know, there’s a big debate taking place about constitutional revision, with the conservatives aiming to change it (especially the war-renouncing Article 9), and the liberals and left wingers defending the original document. I’m politically liberal, but in this case, I think we should actually amend the Constitution – but not in the conservative way. Regarding the armed forces, for example, I think the so-called Self- Defence Forces should become part of the United Nations. As you know, right now the UN doesn’t have a standing army. Instead, its members provide peacekeeping forces on a voluntary basis. It would be great if Japan donated its soldiers (all its armed forces) to the UN in exchange for becoming a permanent member of its Security Council. This way, Japanese soldiers would act as part of the UN standing army. I think it’s a great idea. Actually, even Ozawa Ichiro of the now defunct Liberal Party once had the same idea – even though he proposed giving only half of our armed forces to the UN. His aim was to make Japan more independent of American political interference and control. That’s probably one of the reasons why his proposal was quickly shot down.

It’s a fascinating idea, but I’m afraid many people would be against it, both in Japan and abroad.

T.G.: You think so…? Well, probably (laughs), which is a pity. Think about it: the conservatives want to rearm Japan because, as they say, we have to get ready in case of external aggression. But if we did what I said, we could just ask the UN for help while, at the same time, keeping our pacifist Constitution. You see, it’s always important to think out of the box and come up with new original ideas for old problems. Unfortunately, in Japan, every time an independent-minded politician becomes too important (think about Tanaka Kakuei in the 1970s), the establishment finds a way to get rid of him.

Soon after the events of 11th March 2011 you began to write a column for the Asahi Shinbun newspaper, in which you regularly addressed a number of political and social issues in Japanese society. One of these issues was the controversy around the history textbooks that are used in Japanese schools. What do you think about Abe’s attempts to alter the way history is taught in this country?

T.G.:We always should be aware of how people in power try to alter, distort or suppress history in order to pursue their own interests. The history of mankind is much more nuanced and diverse than these people want us to believe. It’s funny that you should ask me about history books, because a few days ago Zeze Takahisa’s latest film, Kiku to girochin (The Chrysanthemum and the Guillotine) opened in cinemas. While this is fiction, it tells the story of the chance encounter between a real-life anarchist group, the Guillotine Society, which was active during the Taisho period (1912-1926) and advocated gender and class equality, and a travelling troupe of female sumo wrestlers. This film came out just in time because, in April, during a sumo tournament, an official was making a speech in the ring when he collapsed and passed out. Two women (at least one of whom was a nurse) climbed into the ring to assist the official, but a referee urged them to stay out, his reasoning being that the sumo ring is a sacred place and women must stay out. However, Zeze’s film clearly shows that this ban is historically false. Female sumo was quite popular in Japan from the Edo period (1603-1868) until the 1950s. It was mainly based in Yamagata Prefecture and included as many as 20 sumo stables. The wrestlers were mainly country girls who had escaped domestic violence, poverty, and the restrictions of the village community.

Is that why you like this film?

T.G.: Yes, it not only tackles a little-known moment in Japanese history but highlights a social phenomenon many Japanese (including me) have never heard about. It’s also a textbook example of how a storyteller – be it a novelist or a filmmaker – can sometimes take some liberties (e.g. creating the fictional encounter between terrorists and sumo wrestlers) to highlight a particular social or political issue. That is, for me, the power of literature. The work of a scholar may be historically more accurate, but a storyteller is able to put together disparate elements and create a chemical reaction that’s more powerful than any dry scholarly dissertation. In that sense, my works could be seen as word bombs, which I hope are powerful enough to shake people out of their social lethargy.

How about the comfort women issue? Even in this case, the Japanese government has shown a contradictory approach: on the one hand, they’ve paid compensation to some of the victims, but on the other, they keep saying that no official document has been found to prove that the Japanese army was responsible for abducting women and sexually exploiting them. Even now, the authorities are fighting any attempt to build memorial monuments abroad.

T.G.:Obviously, they can’t find any documents for the very simple reason that they destroyed them in the first place. But to answer your question, this is another complicated issue with no clear-cut solution. You can’t simply say that all those women who worked on the front lines were prostitutes, but nor can you say that they were all used as sexual slaves. The situation differed depending on the country where this happened, and who was responsible for their “recruitment”. As a Korean writer said, every comfort woman has her own personal story to tell, and if you put all of them into just one box, you end up losing this diversity. Again, the work of the novelist, of the storyteller, is to focus on these particular stories and give them the importance they deserve, and extract the universal from the particular.

Comfort women, racism, hate speech… How do you think we can stop these negative feelings that seem to have taken root in Japanese society in the past few years.

T.G.: The only feasible way is to be proactive and answer negativity with a positive approach. You have to win them over through dialogue and by offering new solutions. Trying to stop the desert encroaching by building a wall is completely useless because nothing really changes, the desert won’t go away. Instead, you have to find a way to reverse the process and re-green the desert. Is it difficult? Of course it is, and it takes time. But we have to try, and the writer’s duty is to sow the seeds of change.

Three years ago, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, you said that during those 70 years, Japan hadn’t changed at all. What did you mean by that?

T.G.: I meant to say that Japan has become a very rich country (we are the third biggest economic power in the world), but our minds haven’t changed. To be more precise, we’ve forgotten our past. And for me, a country with no historical memory is a country without a future. For example, when debating what to do about our armed forces or the Constitution, we have to remember what we did in the past, what decisions we made then and consider the consequences. However, after the war, the political and social debate has taken a back seat to economic development. Even Abe has built his recent success on a platform of economic recovery (so-called Abenomix). People only seem to worry about jobs and money, and are ready to forgive him anything (e.g. scandals, history textbook revision, the State Secrecy Law, etc.) as long as he can deliver on the economy. The same is true about Japan’s relationship with its neighbours, who have very long memories, especially concerning what we did in Asia during the war. Again, many people are surprised that China and Korea are still grumbling about the past. That’s exactly because we’ve forgotten about it, and the government always tries to downplay what we did to those nations. Our politicians like to portray Japan as a victim, not an aggressor, the ultimate sacrifice being, of course, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, nobody reminds people that even Japan was trying to make its own atomic bomb, and would have used it for sure.

As you said, when people have a good time, nobody worries about social and political issues, as they’re too busy studying for university entrance exams and hunting for a job. Indeed, it’s not by chance that the recent change in public attitude (particularly after the disaster of 11th March 2011) has gone hand in hand with the recession. How would you compare today’s demonstrators with your generation?

T.G.: There’s one big difference: when I was a student, in the 1950s and 60s, our struggle was ideology-driven. Marxism and socialism became very popular among the intellectuals and the students. We really felt we had to fight authoritarianism and consumerism, and change the world. Then, in 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall was followed by the end of communism, and even China opened up to world markets. In Japan, people turned to environmental issues or joined religious cults (e.g. Aum Shinrikyo), and began to volunteer at a grassroots level. Then, in the last ten years or so, the return of poverty and the nuclear disaster in Fukushima have been powerful enough to bring together all these disparate social forces into some sort of movement. Many of these groups (like SEALDs, the student organisation with which I collaborated in 2016) got involved in politics, but they don’t have the same ideological connections we had back in the 60s. They fight about more concrete issues such as protecting the environment, a fair job market, and social justice. They refuse to be led by a party or revolutionary elite, and organise their actions like a sort of diffuse guerrilla group. In a sense, you could say they are closer to the spirit of anarchism.

InTerview by Jean Derome