From the second half of the 19th century, the French capital followed the example of Japan.

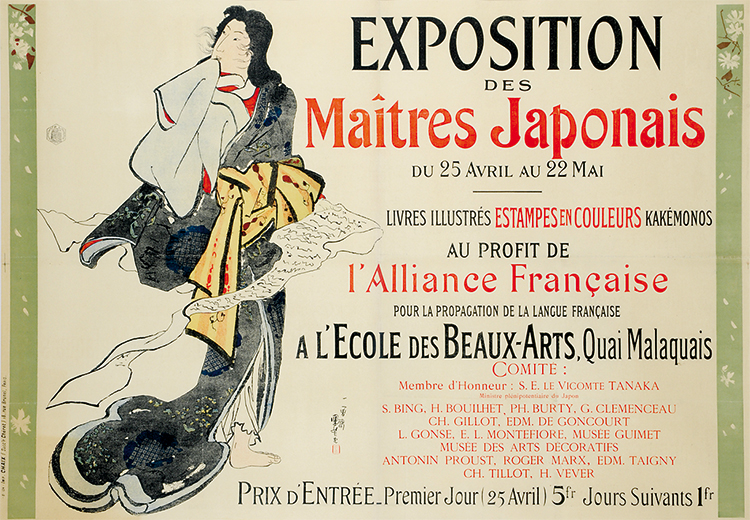

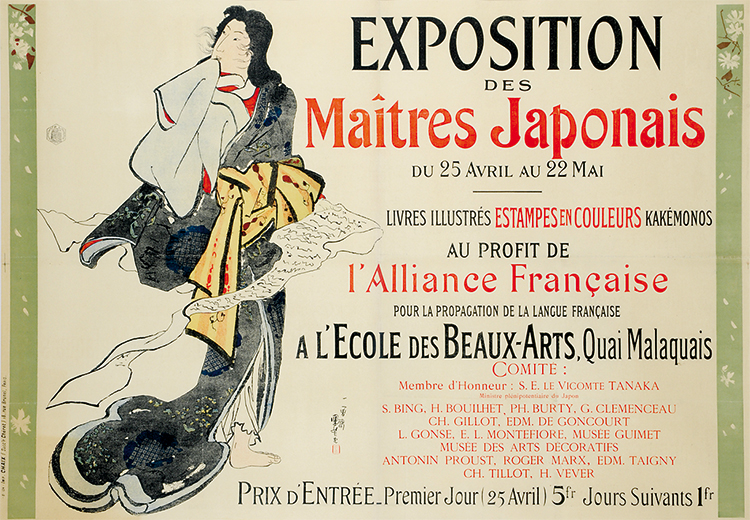

Poster for the 1890 exhibition devoted to Japanese prints.

During the second half of the 19th century, Japanese art held an unparalleled fascination for the West, which generated the extraordinary aesthetic known as Japonisme. The discovery of Japanese arts had a lasting influence on art dealers, collectors and art lovers as well as artists in many fields: painting, architecture, the decorative arts, jewellery, textiles and ceramics. The first Japanese prints arrived in France thanks to the Dutch who remained in Japan during the years it was closed to foreign trade between 1635 and 1845. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until the 1860s that the famous “pictures of the floating world” or ukiyoe began to circulate in large numbers in Paris. Two events helped them to spread among the general public: Japan opening the door to trade with France following the signing of the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce, and Japan’s participation in the World Fair in Paris.

At the time of the World Fair in 1867, Japan was in fashion and had an official display in the Palais de l’Industrie exhibition hall on the Champs-de-Mars. Several thousand objects — textiles, bronzes, ceramics and fans evoked all aspects of Japanese life and aroused great interest among the visitors. The French luxury goods industry helped this new aesthetic to spread, including La Maison Christofle, which produced spectacular and precious enamelled pieces inspired by Japanese decorative motifs. From then on, any arrival of objects from Japan in the capital was greeted by admiring crowds who argued over the prints, lacquerware and china. The popularity of Japonisme continued to grow in the second half of the 1870s, and was at its height at the time of the 1878 World Fair, where Japan was extremely well represented in the stunning Rue des Nations on the Champde- Mars, in addition to a model of a traditional farm in the Trocadero Gardens. The world of fashion, art lovers and critics united to turn Japanese art, which until then had been the reserve of a fringe of the avant-garde, into the object of a real obsession.

The 1889 and 1890 World Fairs did not inspire the same enthusiasm because at the end of the 19th century, the Land of the Rising Sun was no longer the object of fascination it had been in the 1860s and 1870s.

The stories of travellers and traders who visited the Far East encouraged people’s curiosity about Japan. From the 1850s, Parisian tea merchants were importing oriental artefacts including prints. Apart from Bon Marché in rue Boucicaut, most of these shops were on the Right Bank, mainly in the 2nd and 3rd arrondissements. A shop run by Mr and Mrs Desoye in the rue de Rivoli, specializing in Japanese items, was where the first collectors of “japonneries”, to use Baudelaire’s word, used to gather. Simple curiosity gradually gave way to a passion and the development of a more discerning taste for this art form.

Though the art dealers grew in number, two of them played an essential role : Hayashi Tadamasa who, in 1878, arrived to work as an interpreter at the World Fair, and the art dealer and collector Siegfried Bing. The latter, a German manufacturer and ceramicist, opened a shop specialising in Far Eastern art at 19, Rue Chauchat, behind the Hôtel Drouot. During the 1880s, he was one of the dealers who did most to promote Japonisme in France and the world. He also took an active part in the first exhibitions of Japanese art in Paris: in 1883, at the Georges Petit Gallery and, in 1890, at the École de Beaux-Arts, where over seven hundred prints from the most prestigious collections since the middle of the 19th century were displayed, which contributed to Japanese engraving being recognised as an art form in its own right. The exhibition was a revelation for painters of all generations at the time: Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt found new inspiration, as did Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Bonnard, Paul Gauguin and Maurice Denis.

From May 1888 to April 1891, Bing published Le Japon Artistique, a monthly magazine of essays on art and the art industry with editions in three languages — French, English and German — to appeal to an international clientele. Printed by Charles Gillot, it had full-page colour illustrations and provided a fertile source for artists. Hayashi soon went into business as an art dealer and founded his own company in 1889. He became one of the foremost speakers on behalf of enthusiasts of Japonisme in Europe, and was largely responsible for its growth. Though he sold countless prints in the 1890s, he was also the first Japanese collector and dealer of Impressionist paintings by artists who were openly influenced by ukiyo-e (woodblock prints).

The fashion for collecting Japanese works of art inspired a whole raft of the Parisian elite: writers (Baudelaire, Emile Zola, etc.); art critics (Edmond de Goncourt, Philippe Burty, Louis Gonse, Théodore Duret, etc.); sculptors and architects (Edmond de Goncourt, Philippe Burty, Louis Gonse, Théodore Duret, etc.); industrialists and bankers (Emile Guimet, Henri Cernuschi, Charles Haviland, etc.). The last decade of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century were punctuated by largescale public sales of collections of the first devotees of Japanese prints: Burty in 1891, Goncourt in 1897, Hayashi in 1903, Gillot in 1904, Bing in 1906, and many others. The catalogues created for the sales demonstrate the extent of the collectors’ all-consuming passion for the art of that country.

The celebrated art critic, Philippe Burty, was not only one of the first Parisians to collect Japanese art but also the one to popularise the term “Japonisme” when he wrote a series of articles in 1872. His collection was widely displayed during his lifetime, notably at the 1867 and 1878 World Fairs. It was broken up and sold in 1891 in the Hôtel Drouot, and was acquired by collectors — Paul Durand-Ruel, Henri Vever, Georges Clémenceau — and dealers — Bing and Hayashi. Unlike Burty’s collection, which had often been exhibited, the collection of the Goncourt brothers, Edmond and Jules, remained hidden in their almost mythical home in Auteuil, which they bought in 1868 to exhibit their curios in more intimate surroundings.

It was mainly among painters and engravers that the taste for Japanese art held sway in Paris, and was then passed on to other enhusiasts. In the prints, they discovered new ways of using colour, of drawing, composition, perspective and layout, which encouraged them to push the boundaries of their own aesthetic experimentation. The Impressionists drew inspiration from the Japanese prints, which most of them collected, and did not limit themselves to simply borrowing ideas from this exotic and decorative art form. Monet started his collection in 1856, at the age of 16, taking advantage of the packages of exotic products imported into Le Havre. In this way he collected a remarkable two hundred and thirty-one prints, which he hung on the walls of his home in Giverny. Gradually, his interest in Japanese art focused on the decorative effects of certain landscape engravings and the large golden folding screens of the Edo period. The American painter Mary Cassatt, a close friend of Degas, was influenced by the artist Utamaro. Like him, she felt particularly drawn to the theme of motherhood, with close-ups and geometrically straightforward compositions. Unlike Monet, August Rodin only became interested in the fashion for Japonisme sometime later, around 1890. According to his notebooks and letters, he discovered Japanese prints when visiting the Goncourt brothers, and he went to exhibitions of prints in 1890 and 1893. The whole of his collection is testimony to his eclectic taste for Hokusai, Hiroshoge and small traditional artefacts.

The discovery of Japanese art was a profound cultural shock for Parisians. The prints, themes, colours, and exotic influence of Japan had all been largely vulgarized by the press, shows, the numerous travellers’ tales, and posters. The large department stores increased the demand tenfold, brimming over with Japanese goods — kimonos, masks, parasols and fans. From its origins as an aesthetic phenomenon, by the start of the 20th century, Japonisme had become just another commercial strategy.

GAËLLE RIO*

*Heritage Curator, Petit Palais, City of Paris Museum of Fine Arts