To coincide with the opening of a season devoted to Japanese culture, we invite you to discover the origins of Japonisme in France.

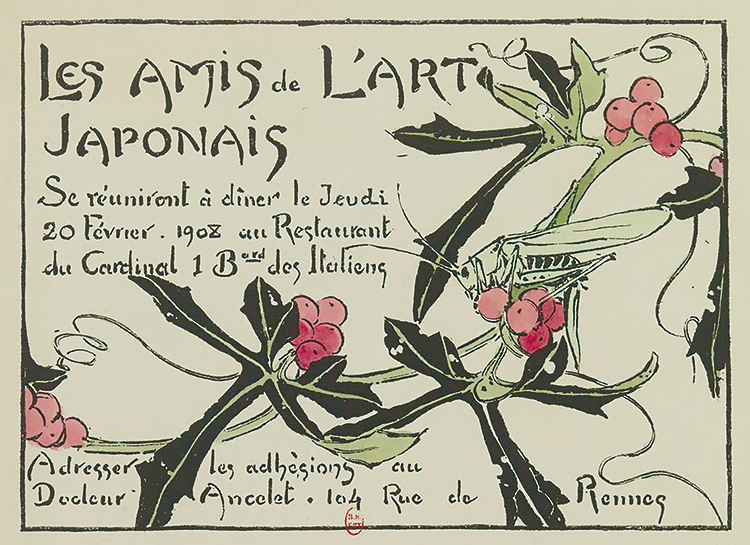

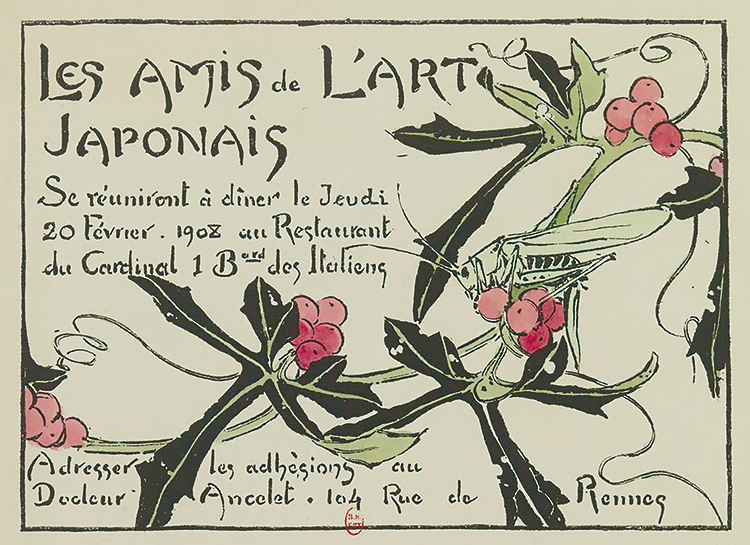

It was thanks to the initiative of Siegfried Bing that the Society of Friends of Japanese Art came into being. Its meetings were announced on cards decorated “in the Japanese style”

How can we define the movement known as “Japonisme”? Though the term was first used in 1872 as the title of a series of articles published by the art critic Philippe Burty in the magazine La Renaissance littéraire et artistique to describe the influence of Japanese art on Western art, it’s difficult to summarise everything it represents. In 1988, at the time of the exhibition Le Japonisme at the Grand Palais in Paris, the visionary art historian Takashina Shuji, suggested that the word should be used in the plural as the meaning of the concept was so broad.

Geneviève Lacambre, chief curator of the event and one of the first to take an interest in this artistic phenomenon, rightly pointed out that there were four stages in the development of this artistic movement. It began with the introduction of Japanese motifs, then exotic and naturalistic Japanese designs were copied. This was followed by the imitation of sophisticated Japanese techniques and, finally, the careful study and analysis of the principles and methods found in Japanese art. After its discovery and subsequent adoption, it culminated in being assimilated.

The term “Japonisme” is generally associated with art, but it shouldn’t be forgotten that it influenced many other areas such as fashion and architecture. It also played an important role in literature. The novels of Pierre Loti, especially Madame Chrysanthème, found fame beyond France, and both Judith Gautier and Edmond de Goncourt, to mention the two best known, greatly encouraged the enthusiasm for Japan through their writing.

Japanese art didn’t wait for Japan to open up commercially to make inroads into Europe. The Dutch working for the Dutch East India Company in Dejima, situated off the coast of Nagasaki, exported Japanese goods through Batavia (modern- day Jakarta). There were also numerous Chinese traders in Nagasaki at the time, and all this commercial activity helped engravings, fans and other artefacts to reach the West. From the 1820s, there were shops selling tea and Japanese curios in Paris. La Porte Chinoise (The Chinese Gate), often mentioned in the writing of the Goncourt brothers, opened in 1826, at 36 Rue Vivienne, and began to sell Japanese lacquer ware from the 1860s onwards. Collectors of curios, such as Charles Baudelaire and Philippe Burty, often gathered there.

There are many claimants to the title of “discoverer” of Japanese art. The name of Baudelaire, who could have bought prints in 1861, is often mentioned, but he never lay claim to it. The art historian and chronicler Léonce Bénédite maintains that it was, in fact, the gifted engraver Félix Bracquemond. In 1856, he found in his printer August Delâtre’s workshop “a little book curiously bound in paper with a red cover. The book had come from a great distance. As it was soft and pliable, it had been used as a wedge to protect some Japanese china. Bracquemond was curious, opened it and was immediately struck by its contents: supremely lifelike and expressive sketches of jugglers, dancers, children, animals, insects and flowers”. Delâtre didn’t want to part with it, but, a few months later, Bracquemond obtained it and showed it to all his friends. Neither he nor the other Japanese art enthusiasts were aware that this little book was none other than a volume of the Hokusai Manga. Bracquemond became one of the most fervent adherents of Japonisme and was the designer of the famous “Rousseau” table service, for which he used the drawings of Hokusai and his disciples as a template, placing the motifs asymmetrically, and thus creating a new style in ceramic decoration.

It was at this time that artists and writers also discovered Japanese prints. While the Japanese thought they only had value as a fun or educative art form, and it never occurred to them that they should be preserved, the Japonisme enthusiasts coveted them with a passion. “The arrival of the first prints caused a real commotion. […] The most modest collection was fought over heatedly. People went from shop to shop searching for new arrivals. […] The drawings were especially prized by painters and knowledgeable art lovers. They arrived in their thousands, and though often spoiled by sea water, they were snapped up rapidly. To begin with, the art dealers were taken aback by this craze; then, encouraged by easy sales, they were able to sell these items in quite large quantities”, it was reported in 1867.

Soon, dinner parties were arranged for followers of Japonisme, which “brought together these enthusiasts; the only subject discussed was prints, and it was usual for everyone to bring some with them for their colleagues to admire”, as the collector Raymond Koechlin explained. They argued about which were the most beautiful, but they knew practically nothing about the original painters. There was only one of them who not only collected prints and other items but also devoted a monograph each to two great Japanese artists: Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896) who wrote Outamaro (1892) and Hokusai (1896).

It was in the midst of this feverish obsession for Japonisme, where friendships were made and competition was rife, that a young Japanese man, HAyASHITadamasa, arrived to work as an interpreter at the Paris World Fair in 1878. He stayed in France for more than 25 years, studied art history tirelessly, and became the most famous art dealer of the period. He was greatly respected by all those involved in Japonisme, and was especially sought after by collectors who wanted to know more about Japanese artists. He taught them how to recognize genuine Japanese art, which was often very different from what they imagined, and and explained that prints represented only a minute part. Hayashi Tadamasa became general commissioner for the Japanese section at the 1900 Paris World Fair, and brought the beauty of traditional Japanese art to the attention of the world.

The role played by the art dealer Siegfried Bing was as important as Hayashi Tadamasa’s. When Japonisme, which reached its height between 1878 and 1880, became widespread throughout Europe, he had the idea of creating a sumptuous publication called Le Japon artistique which appeared in French, English and German editions. Its 36 monthly issues were richly illustrated and written by renowned Japanese art experts, and was praised for its beauty and content. Siegfried Bing’s magazine introduced Japanese art and handicrafts to French and other European artists, who were able to use them as models and inspiration for their work.

All the artists of the second half of the 19th century, whether consciously or not, were inspired by the beauty, flat colours, fine lines, etc., of Japanese prints. However, they were unaware that artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, in their turn, had been influenced by Western art and European drawing, which had helped create this art they considered to be “so Japanese”. But the prints had arrived at a moment when Western art was looking for new ways of expression, and they became a source of inspiration for artists. The Japonisme movement began to die out at the turn of the century. The prints had become very expensive, and following the joy of their discovery, all the new ideas gained from Japanese art had been assimilated. Hayashi, Goncourt, Burty and many others stopped collecting at this point.

It was almost a century before the appearance of the Neo-Japanisme or New Japonisme art movements, which were very different from what had occurred in the previous century. In the 1980s, the enthusiasm for manga and Japanese culture among the younger generation led to a renewed fascination for Japanese culture. The surprise and delight aroused by the Japanese cult of “kawaii” (cute), and the work of contemporary artists like Murakami Takashi drawing on the roots of traditional culture to create artwork that was original and fun, have given birth to these multiple “Japonismes”, which will be celebrated in France throughout the coming year.

BRIGITTE KOYAMA-RICHARD*

*Professor, Musashi University, Tokyo, She is the author of numerous books including Beautés japonaises (2016) and Yokai (2017), Scala editions.