A documentary and fiction film-maker, Funahashi Atsushi has numerous ambitious projects.

FuNAHASHi Atsushi considers that cinema can help audiences makes their own minds up about the state of the world around them.

Though he has gained international recognition with his documentaries such as Futaba kara toku hanarete (nuclear nation, 2012), Funahashi Atsushi also makes outstanding fiction films using documentary techniques. His open-minded approach makes him one of the most interesting directors of his generation.

Your career as a director started in America, where you went to study film-making after graduating from the University of Tokyo. FUNAHASHIAtsushi : Yes, when I was in Japan, I made a few small 8mm films, but I focused mainly on film studies (cinema history and theory). My professor was Hasumi Shigehiko, a very influential film critic, among whose students were several future directors such as Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Aoyama Shinji, and Suo Masayuki. Back then, I wasn’t really thinking about making films; I was more like a cinephile.

And then you went to America.

F. A. : Yes, I was admitted to both the American Film Institute in Los Angeles and the School of Visual Arts in new York. I was mainly into indie films (Jim Jarmush, Spike Lee), and I wanted to make something like that myself, so I chose the latter school. Then, after shooting a few 16mm films, I made my debut with Echoes (2002) with a crew made up of local and international students, and a cast of new York-based actors. The great thing about indie films in new York is that there’s a huge pool of aspiring actors who are available for free. I really liked that community. So I ended up staying for ten years, making my films while working as an assistant director for a living.

Do you have any particular memories?

F. A. : I was there when 9/11 happened. new York was, and still is, full of democrats, but soon after the terrorist attack, everybody was pro-war. I knew a lot of liberals, and they all started talking about vengeance and retaliation. To me it was horrifying. But I realized that you could be the most tolerant person in the world, but when something like that happens to you, when your city gets bombed, your mindset shifts completely and you’re going to change – at least many people did.

Is that when you decided to make your second film, Big River, in 2005?

F. A. : Exactly. This is the story of the strange friendship between a Pakistani guy, a trailer-park white girl, and a Japanese hitch-hiker. The story is based on the real-life shooting of a Sikh man in Arizona, soon after 9/11, by a white guy who claimed he was protecting America. I felt like America had gone back to the frontier period, with cowboys shooting Indians. That country can be really scary, especially the “red” states controlled by the Republican Party. And the cops can do whatever they want and get away with it.

In an old interview you gave about Big River, you said it was easier to work in English because it allowed for more flexibility and far less red tape. And yet you eventually returned to Japan.

F. A. : One of the main reasons for leaving the uS was that making films there is a constant struggle unless you’re really successful. I wanted to work regularly, not just making one film every five years, so I came back to Japan where I had some connections. Big River was co-funded and co-produced by Office Kitano (Beat Takeshi’s company). One of their producers, Ichiyama Shozo, who is also the Tokyo Filmex festival’s programme director, helped me a lot getting work here. At first, I had to take a few jobs I wasn’t completely happy with, but, little by little, things took off and I was able to do what I really wanted to do.

How would you compare America and Japan now?

F. A. : Production-wise, Japan and America are just different. There are pros and cons in both places. The good thing about Japan, for example, is that people work fast and are very efficient. But on the other hand, everything is low budget. Actually, the two things are intertwined: the schedule must be tight exactly because there is little money available. So you have to think hard about how you can get things done quickly, maybe squeezing three scenes together into one. When I made Big River, I was shooting about 15-18 shots a day, but in Japan, when I worked on my first TV drama, I was required to shoot 120 shots a day, which is impossible unless every member of the crew does their job properly. So while you’re shooting one scene, other people are already working on the next shot, and when I get to the set, it’s ready to roll. There’s no wasted time. The bad thing about this system is that there’s no room for originality, improvisation or last-minute changes. There’s a mass production approach to story-making here.

No wonder over 600 films a year get made in Japan.

F. A. : Yes, but, actually, only a few are seen abroad because most of them are made with only a Japanese audience in mind. So when they’re shown at an international festival, people don’t understand what’s going on. That’s why I always try to make films that are universally relevant. As long as you have a powerful story, you can overcome language or cultural barriers.

In Japan, you’ve spent a lot of time making films that, in one way or another, are connected to the events of 3/11.

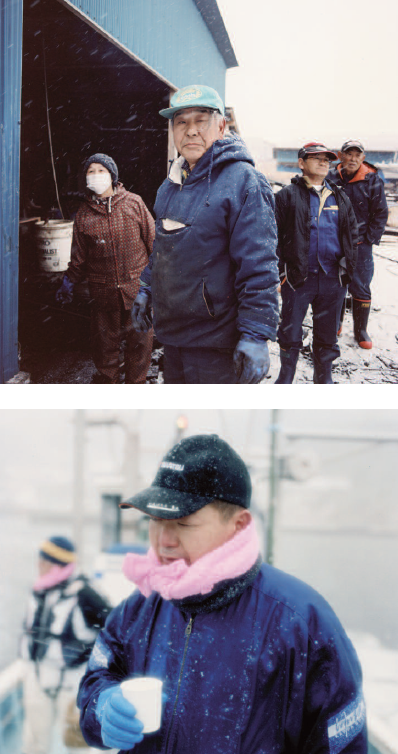

F. A. : It all started when the filming of what would later become Cold Bloom was cancelled three weeks before we were scheduled to start shooting, because of the triple disaster in Fukushima. Everything was ready, half of our budget had already gone in pre-production, and then we had to abandon the project. So I found myself with nothing to do for the next 3-4 months. That’s part of the reason why I started working on nuclear nation: I had no job, and I spent all the time watching TV. Then at the end of March, I saw the news about Futaba. The town is inside the exclusion zone closest to the Fukushima power plant. So its entire population was evacuated out of Fukushima and into an abandoned high school in Saitama Prefecture, just north of Tokyo. I thought I could make a film about the nuclear disaster without actually shooting Fukushima, just focusing on the people in the school. That’s how nuclear nation was born.

Why did you decide to make a Nuclear Nation Part 2?

F. A. : Because the nuclear crisis is not over yet. That’s why we’re still filming. We’re now working on a third instalment; it’s become a sort of ongoing project. I feel human beings can be so short-sighted that it’s cinema’s role to capture what’s going on now as a record, so people can watch it later on. When you’re in the process of doing something, and you’re caught in the middle of it, you often can’t think straight and make the right decisions, but in ten or twenty years it’s going to look different. In this sense, cinema is a good tool to make people think about the meaning of life.

Eventually you managed to make the film that had been cancelled because of the 3/11 tragedy, and it became Cold Bloom.

F. A. : Yes, I talked to Office Kitano, and they liked the project enough to help me put the money together. For me, it was like a miracle because I thought I’d never be able to make it.

Is it the same story?

F. A. : Yes, but with a different cast because the original actors were not available anymore. Actually, because we shot the film after the events of 3/11, the story took on an additional meaning. It was a different way of dealing with the disaster. It’s not about 3/11, but because of the location and the story, it deals with the subject in an elliptical way. It’s about the emptiness all these people felt having lost their family, their home, and their community. And their anger for what TEPCO and the government had done to them. For me, as a filmmaker, it’s better to step back and put some distance between a fictional story and real life. In other words, I didn’t want to make a film about Fukushima. The disaster only happened seven years ago, and if you fictionalise it, it doesn’t feel real. I don’t think fiction should be used like that. Otherwise, you end up making one of those American films that are so fake. Oliver Stone, for example, shot World Trade Center in 2005 i.e. only four years after 9/11, and people in new York hated it because it’s a stereotype hero story, and it feels so cheap.

When you’re interviewed, most people seem to focus either on your American period or the Fukushima-related films, and your film from 2009, Deep in the Valley, is always overlooked. That’s is a pity, partly because it’s about this area in eastern Tokyo called Yanaka.

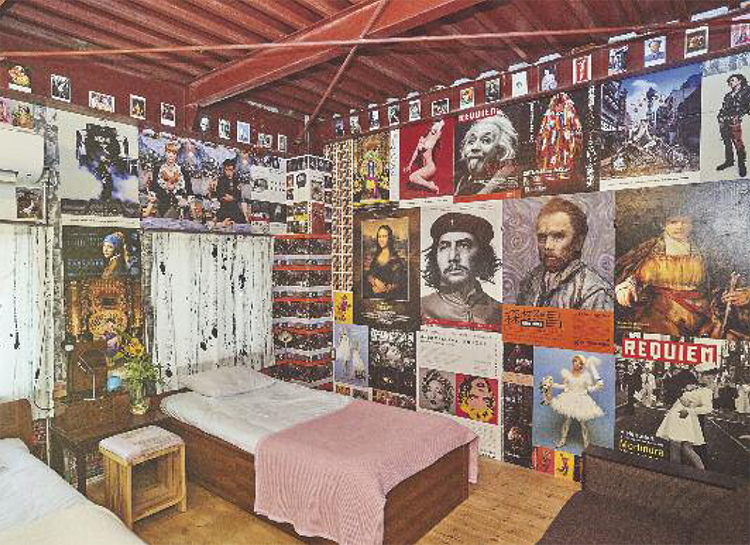

F. A. : That’s where I live. That’s why I made this film. Anyway, I’m glad you like it. It’s a small indie film, and one of my favourites. I guess you’re one of the few people who saw it. At the time, it was only shown for a couple of weeks in a small theatre in Shinjuku, and that was it. There isn’t even a DVD available.

You’re one of the few directors who makes both feature films and documentaries, and the interesting thing about this film is that you actually mixed the two things together.

F. A. : You know, whenever I make a fiction film, people say it looks like a documentary, and when I make a documentary they say it looks like fiction (laughs)! To be honest, I like to mix the two genres in order to overcome what I see as their shortcomings. On the one hand, when people make fiction films, they tend to become pretentious – like actors showing off their stuff. I just hate that. I want them to come down to earth. I love real people, so the actors should just be real, natural in their acting. On the other hand, there’s a sort of pretentiousness in documentary film-making too. Many directors tend to overlook aesthetics when shooting, especially in Japan. In other words, they think that if what we show is the truth, it doesn’t need to look beautiful. So you have plenty of headshot interviews and shaky cameras. I disagree. You can still show the truth through a beautiful shot. So I really want to combine these genres no matter what project I work on. I’m still struggling, trying to find the best way to shoot my films. This summer I’m actually going to make a new film in Kagoshima. I’m making a documentary first and then, next year, I’m going to shoot a feature film based on the documentary. Right now, we’re thinking about keeping the films as two different projects, but you never know. The main idea is that I’ll be meeting many people while making the documentary, and I’m planning to use some of those people to make the feature film.

How did you work on Deep in the Valley?

F. A. : At the time I was teaching at an acting school, and as I said, I was bothered by their approach to acting. When you look at the people living in Yanaka – like this old blind woman who cleans the graves in the cemetery and knows each and every grave – they’re so real and so strong, I wanted my students to watch and learn from them. So I came up with the idea of making them work together in the same film. That’s how the project came about. In Yanaka, there used to be a five-storey pagoda that burned down a long time ago, and the driving force of the story is the search for a lost 8mm film of the burning pagoda. The couple looking for the film are acting, but at the same time, they have to talk to the locals in their quest for the film, and that’s the documentary part. We also created a fictional story about the carpenter who built the pagoda in the Edo period. In Japan, many local communities are disappearing and, for me, the pagoda was the symbol of something that went missing in this once tight-knit community in Yanaka. In that sense, finding the lost film wasn’t really important. But the funny thing is, they actually found the film during the shooting! So you can see this element of reality changing the fictional story, which is very interesting to me.

Speaking of reality, and documentaries, your latest project is this film you made about NMB48, an idol group from Nanba, Osaka, that is part of the AKB48 franchise.

F. A. : That’s another interesting story because Akimoto Yasushi – AKB48’s creator and producer – wanted to make this documentary, but he was fed up with the way previous films all looked the same. So he asked his assistants to find someone who had nothing to do with idol groups, knew nothing about them and had no interest in them. And they said, okay how about this Fukushima disaster documentary guy (laughs)? That’s how I got offered the project. And my first reaction was, why me?!

Were you free to do whatever you wanted? I’m asking because I know that Akimoto is very protective of his idol empire, and there are things the media and the press cannot really say, especially in Japan.

F. A. : I had final cut. That’s something I insisted upon. Then, of course, there’s a sort of unwritten rule that you don’t want to criticise or disrespect AKB48. They produced the film, after all, and you don’t want to slam them too directly for their greediness or the way they manage those girls. So I tried to do it in a more roundabout way, trying to imply what was really going on. I adopted a flyon- the-wall style to just show what was in front of the camera. Then it’s up to you to interpret those scenes and form your own opinion.

What do you think about the lack of support for cinema on the part of the Japanese government?

F. A. : Actually, the Ministry of Culture offers some subsidies, but they’re not for low budget films. In order to apply, your film must have a budget of at least 50 million yen. If you’re an independent film-maker like me, and your typical budget is around ten million, you won’t see any money. In other words, they’re not helping those who really need the money. They’re just helping to support the big companies, which makes no sense at all.

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME