Not so very long ago, people with leprosy were cut off from the world and had no choice in what they ate.

Film director Kawase Naomi tackles the fate of former sufferers of Hansen’s Disease in Red Bean.

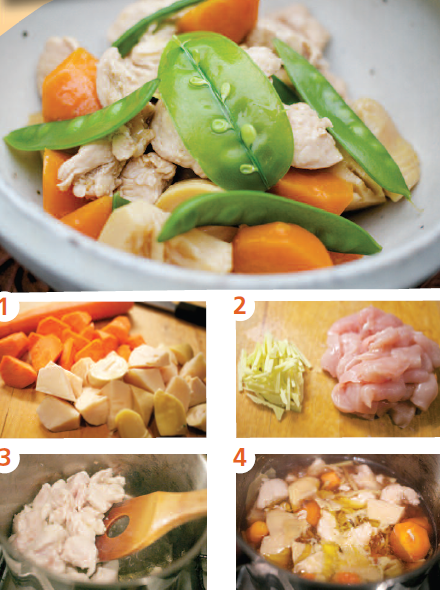

Those who have seen Kawase Naomi’s film Sweet Bean or read the novel Sweet Bean Paste by Sukegawa Durian (trans. by Alison Watts, Oneworld), which inspired it, will be reminded how people with Hansen’s Disease (leprosy) used to be segregated from society. Some of the film was shot in Tama Zensho-en Sanatorium, west of Tokyo. From the beginning of the 20th century, the Japanese government adopted a policy of lifelong incarceration for sufferers of Hansen’s Disease, creating sanatoriums aimed at isolating rather than caring for them. Cut off from the outside world, the patients had to work in a supposedly self-sufficient system as far as providing food for themselves was concerned. A large vegetable garden and orchard were set up in the vast grounds of the sanatorium where pigs, cows and chickens were also raised. Cultivating plants or looking after animals can be a source of joy to patients, but it was not as idyllic as it appeared. The hard labour was exhausting and made them ill. At mealtimes, they each had to take heavy bowls, which they carried to the vegetable garden. One witness reports a case of blind patients toiling back and forth in the snow… During the 1940s, due to the war and lack of food, 300 people died in sanatoriums.

After the war, nutrition improved for these patients, but they still had no choice about what they could eat. At that period, when food for the general population was becoming more varied, they were often forced to eat identical meals. After staging protests, they demanded the right to choose what to eat, to have special meals for the elderly, even to pick their own ingredients and cook them themselves. This allowed them to season food as they liked, and to have hot meals.

Hansen’s Disease deforms a person’s body and often affects the eyes, but it has very little affect on taste or smell, which means they become even more important to those who have the disease. Fujimori Toshi, a former resident, recalls that, “Even if you forget your age, you never forget the meals on your first day in the sanatorium.” She remembers vividly when a friend was unable to swallow her first meal. “For some, it represented shame, for others it was peace, an opportunity to escape from discrimination, or it was virus filled air, or even a flame which destroyed ties with family and friends forever,” she says trying to bring their predicament to life.

It’s not enough just to consume the required calories to live. Segregation not only separates people from the world but, removes “the freedom to eat when and what you want”, which can sometimes mean eating badly, eating alone, even not eating at all. These are the small details that allow us to live as independent individuals, and they are crucial to making our lives our very own.

SEKIGUCHI RYOKO

INFOS PRATIQUES

TAMA ZENSHOEN SANATORIUM

4-1-1 aobacho, higashi murayama-shi, Tokyo 189-8550.

www.mhlw.go.jp/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/hansen/zenshoen/