From its time as one of Tokyo’s culture centres, Shinjuku has experienced profound upheaval.

Shinjuku in 2018, photo by Jérémie Souteyrat.

after spending the last 25 years of my life in Tokyo, I can say more than ever that I’m in love with this city. When it comes to exciting, vibrant places, Tokyo is second to none. To my great regret, though, the only area in which Japan’s capital loses out to Paris, London or Rome is urban and architectural heritage. After being destroyed more than once by natural and man-made disasters, there’s precious little left from the city’s past – and when I say “past” I mean the relatively recent postwar period.

Even Shinjuku wasn’t spared, as 90% of the area around the station was levelled by the American air raids that battered Tokyo from May to August 1945. However, the district retained its pre-war road system. Even more extraordinarily, though large swaths of Shinjuku have changed completely in the last 50-60 years, some of its more distinctive spots have survived rampant urban development. Starting at the square in front of the station’s east exit, we find what is arguably one of Shinjuku’s oldest relics. Today, it’s called Minna no izumi (Everybody’s Fountain), but when London donated it to Tokyo, at the turn of the 20th century, it was called Basuiso (literally “water tank for horses”) as it provided water for both people and animals. Only three such fountains survive today worldwide. The round building just behind it is the station carpark. Both of them can be clearly seen in a rare colour scene about halfway through Oshima Nagisa’s Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1968).

One of the neighbourhood’s more striking constructions stands right next to the station: the Yasuyo Building was completed by architect Taniguchi Yoshiro in 1969, and even today is famous for housing Kakiden, a long-established restaurant which occupies the 6th to the 9th floors and has interiors designed by Taniguchi himself.

Walking down Shinjuku Street, no history of local architecture would be complete without mentioning the Kinokuniya Bookstore Main Building (1964). Being squeezed between other less impressive buildings, it’s easy to overlook, but for more than 50 years it’s been the heart of the local cultural scene.

Shinjuku used to be full of jazz cafes and clubs, and one of the most famous, the Pit Inn, was right next to Kinokuniya. Opened in 1965, the 40-seater quickly became the favourite live venue for all the local jazz greats from saxophonist Watanabe Sadao and pianist Yamashita Yosuke to trumpeter Hino Terumasa and singer Asakawa Maki. Pit Inn has moved three times since, and its current incarnation can be found in a backstreet towards Shinjuku’s eastern outskirts.

Speaking of long-gone cafes, in the late 1960s all the rebels and arty people used to gather at Fugetsudo. Here, you could find poets such as Takiguchi Shuzo, Shiraishi Kazuko, and Tanikawa Shuntaro, actors like Mikuni Rentaro and Kishida Kyoko and, of course, all-round creator and enfant terrible Terayama Shuji (whose main base was actually Shibuya). According to butoh (Japanese dance theatre) veteran Maro Akaji, it was here that he first met playwright Kara Juro (who at the time was busy shaping his Situation Theatre inside the infamous red tent). Then from the late 1960s, more and more hippies made their appearance, apparently using and selling marijuana and LSD. Unfortunately, the place was closed in 1973, but you can still enjoy a whiff of retro cafe culture (albeit in a more domesticated, bourgeois atmosphere) at L’ambre, which, by the way, is very close to the location of the old Fugetsudo.

Near L’ambre, you’ll also find another Shinjuku landmark: the Isetan department store. The massive Isetan flagship store was built in 1933, in the thenpopular art-deco style, and has miraculously survived the air raids. Today, it’s considered to be the face of Shinjuku and one of the most influential department stores in Japan. It’s well worth a visit (pay attention to the elegant architectural details) even if you’re not in the mood for shopping.

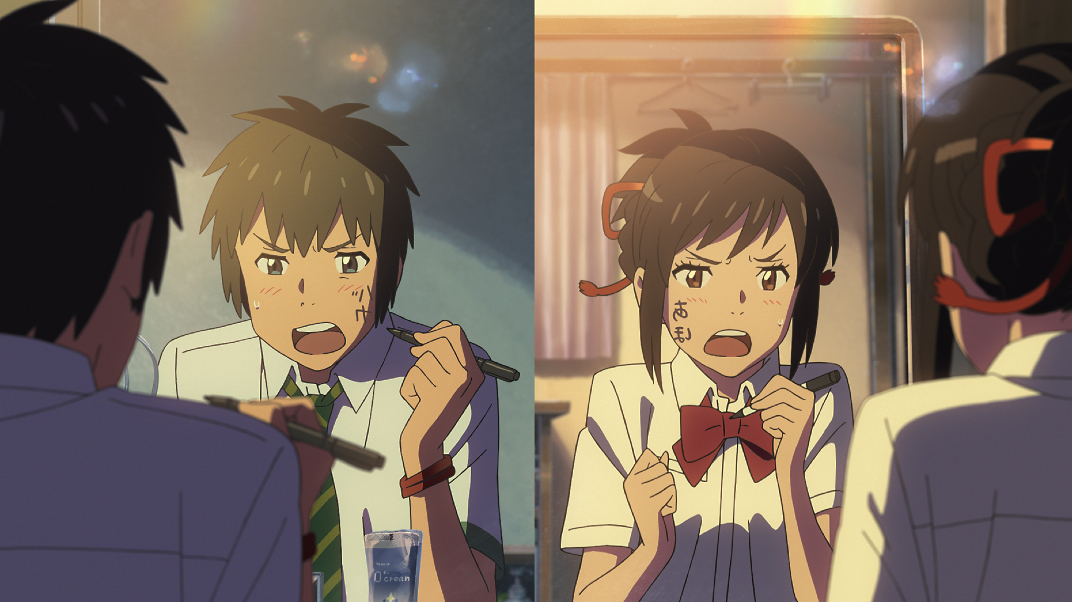

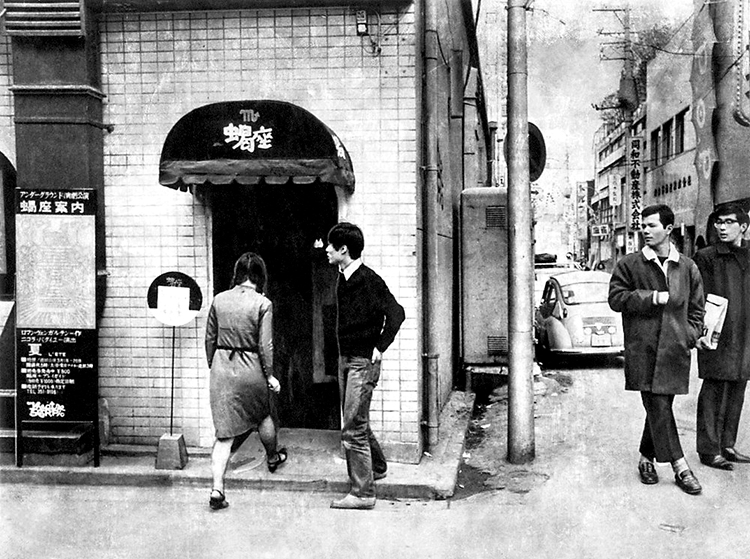

The place is particularly packed during the holidays, so you can imagine people’s shocked reaction when the police box in front of Isetan’s main entrance was bombed on Christmas Eve 1972. On Meiji Street, about 100 metres from the police box and facing Isetan, there was (and still is) the Art Theatre Guild’s Shinjuku Bunka – the “only” difference with the past being that fifty years ago this place (and the Theatre Scorpio in the basement) spearheaded Japanese cinematic avantgarde by screening both foreign art films and works by up-and-coming local talent, while now it’s just a run-of-the-mill cinema like many others in Tokyo.

In the basement of the Art Theatre Guild’s Shinjuku Bunka you’ll find the Sasori-za (Theatre Scorpio) where both foreign and Japanese avant-garde films were shown.

While the eastern area of Shinjuku closer to the station has retained its old layout through the decades, the Kabukicho red-light district was in such a bad state at the end of the war that it underwent a complete reconstruction. Smack in the middle, surrounded by strip joints, was Shinjuku Art Village, a small theatre devoted – believe it or not – to butoh. As they never bothered to advertise their performances, at any one time there were usually fewer than ten people in the audience – including a few drunks who’d come in by mistake. Needless to say, it didn’t last long; it moved to Meguro in 1974.

Nothing has as strong a nostalgic vibe as trams. In Tokyo, alas, most of the extended tram system (181km of track) was closed between 1967 and 1972 because of financial restructuring and a sharp increase in car traffic. In Shinjuku the trams stopped running in 1970. Four years later, an S-shaped section of the track east of Kabukicho was converted into the Shinjuku Promenade Park Four Seasons Pathway, a pleasant greenery-filled corridor leading to the local cultural centre. The Pathway is also the western border of the Golden Gai, an incredibly cramped area featuring about 200 tiny shanty-style bars and clubs. Originally known as the poor-man’s Yoshiwara (red-light district), it replaced sex with booze when prostitution became illegal in 1958, and by 1968, it attracted a varied crowd of artists, musicians, actors, journalists and other assorted intellectuals. In the 1980s, the decrepit bars became the target of the yakuza (organised crime syndicates) who tried to set them on fire so that developers could buy up the land, but a group of supporters saved them by guarding the area at night. Today, Golden Gai is still going strong. It may have lost some of its mystique and hard edge (now many bars welcome foreigners and proudly declare “no seat charge” on the door), but it’s probably the only place left in Tokyo where one can experience the city as it looked soon after the war. Indeed, some of those bars are more than 50 years old.

The complete opposite (not only geographically) of Golden Gai can be found on the other side of the station. Until 1968, there used to be a huge “hole” in west Shinjuku: the Yodobashi Water Purification Plant. Opened at the end of 1898, it was Japan’s first modern water works with a capacity of 140,000 cubic metres of water per day. The plant got bigger and bigger over the years in order to satisfy the increasing demand for clean water, until it was closed fifty years ago. This is, hands down, the one lost piece of Tokyo I wish I could have seen with my own eyes.

Today, that hole has been filled with a forest of high-rises. Some of Tokyo’s tallest and bestknown buildings are here, from Tange Kenzo’s Tokyo Metropolitan Government Office to the unusually designed Mode Gakuen Cocoon Tower and the Park Hyatt Hotel.

GIANNI SIMONE