Rey Ventura, from the Philippines, agreed to revisit the places where he lived as an immigrant in Japan

Ishikawacho Station on the JR Negishi Line is very well known to tourists, gourmets and weekend ramblers. Located less than four kilometres south of Yokohama Station, it’s a useful starting point to spend a leisurely Sunday. Once out of the station, everybody turns right, towards the sea, and depending on their inclination, heads to Chinatown’s eateries, Motomachi’s upmarket shopping street or Yamashita Park, which runs along the waterfront. But if, by mistake, you turn left instead and pass under the elevated Metropolitan Expressway, you’ll enter a totally different world of drab grey buildings, off-licences, greasy spoons and doya (dosshouses).

This is Kotobuki-cho, which used to be one of Japan’s biggest and most notorious yoseba (place where day labourers gather to get work). At its peak, during the Economic Bubble years, the two dozen or so blocks that comprise the district were home to about 5-6,000 workers, mainly employed in construction, roadwork or as stevedores in the Port of Yokohama. Today, though, no more than 1,000 active labourers are left, as most of the 6,500 residents are too old and sick to work. During the 1980s, a sizeable part of Kotobuki-cho’s population consisted of foreigners – especially Koreans and Filipinos. One member of the latter group, Rey Ventura, went on to chronicle life in the yoseba (he is the author of the groundbreaking memoir Underground in Japan) and Filipino migration to Japan. Ventura is now a university teacher, but he has not forgotten his old home – or “crime scene” as he jokingly calls it – where some of his friends still live, and he was kind enough to guide me around the district. “Recently, I haven’t been here at 4 or 5 in the morning when they gather in the hope of getting a job, and as for the daytime population, they’re all quite old and sick,” Ventura says. “They no longer have the money and energy to go to the bars to drink and have fun.”

The place where Ventura used to live is still standing, but some of the area’s other main features have gone, including the old labour exchange on Kotobuki-cho’s main intersection. They’re building a social welfare centre in its place, in order to keep up with the district’s new demographic situation. “Right now, the local authorities’ main worry is how to look after this increasingly elderly population,” Ventura says. “Many of them came here looking for work in their late teens and have lived in Kotobuki for the last 40-50 years.” A lot of them now depend on welfare payments to survive. Across the street from the future welfare centre, Ventura introduces me to one relic from the past: the only public toilet left in the neighbourhood. Inside we discover graffiti next to the sink, written in Tagalog. Ventura reads the phrase and bursts out laughing because he knows the guy who wrote it (he actually signed it). “It reads, ‘You are a shit, not me’, he explains.”

On another corner of the intersection stands a grocery store – the focal point of the neighbourhood, and arguably its liveliest spot, as there’s always a group of people gathered in front of it, drinking and chatting. “All these places, including the grocery store, are owned by Koreans,” Ventura says. “You could say this is Yokohama’s unofficial Korean Town. Of course, these people are the younger generation. They’ve all adopted Japanese names. They’re hard workers and make quite a bit of money, but they don’t display their wealth.” In honour of the old days, Ventura proposes a toast. So we grab a drink and stand on the corner, like everyone else. Ventura sips a cheap “one-cup” sake, like an old-school tachinbo (day labourer). “I remember when this place used to be swarming with people looking for a job early in the morning,” he says, “and after work everybody would gather in the streets drinking, chatting and having a good time.” The current scene couldn’t be more different. Many of the men around us are old, poor, sick and, most of all, they look lonely. “Things have changed so much now, but I believe the system won’t disappear, because the big companies will always need day workers. There may be ups and downs, but the economy requires them, especially now with the Olympic Games coming up.”

Next, Ventura takes me to the oldest doya remaining in the area. Its rooms are only two-tatami wide (fewer than four square metres). Currently there are about 8,000 cheap rooms for rent in Kotobuki- cho. Many of them are used by the city of Yokohama to house welfare recipients. The doya’s gloomy-looking exteriors are in stark contrast with the colourful Yokohama Hostel Village (www.yokohama. hostelvillage.com), a self-styled “backpackers and budget travellers inn”. “Apart from the young foreign tourists who stay here because it’s so cheap, you hardly ever hear foreign-sounding people anymore,” Ventura points out.

When Ventura arrived in Yokohama in 1988, many Filipinos saw Japan as the promised land. “Many things have changed since,” he says. “Our economy has been growing very fast and the middle class has greatly expanded. Now, if you walk around Manila at night you can see many young people having fun. They have mobile phones and other gadgets. I’d never seen anything like that before. When your life is that good you lack the kind of drive and strong desire needed to leave your family and friends to work abroad.”

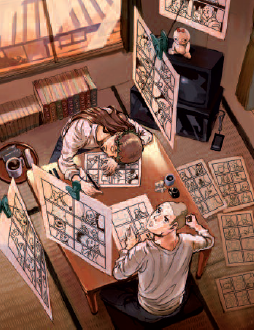

However, even though circumstances have changed, many Filipinos still choose to migrate (ten percent of the country’s GDP – about 20 billion dollars – comes from the money migrants send home), and many of them see the attraction of moving here. “For one thing, Japan is only a four-hour flight away from the Philippines,” Ventura says. “Even more importantly, as the Filipino community is now well established, most immigrants have some relative or friend here who can help them settle down. Of course, the kind of work the new immijean derome for Zoom japan march 2018 number 59 zoom JaPaN 13 grants do is vastly different from my generation. Now, there are nurses and caregivers, IT professionals and English teachers as well as traditional manual workers such as housekeepers. On the other hand, coming to Japan as an unskilled worker has become very difficult, and it’s almost impossible for women to get an “entertainer” visa.

“The entertainers you can still find now are the old Japayukis who came in the past. They’re now married to Japanese nationals, but they’re all obasan (middle-aged women) now. They moonlight as caregivers or work in factories and supermarkets during the day, and at night they work in a bar as entertainers. All these ladies, more often than not, are the main breadwinners in the family because their husbands are elderly men who are now retired or are not earning enough. There’s a wide age gap between them – about 15-20 years. They have to keep working hard because they have children and have to pay for their education. Also, many of them are now separated from their partners. This is an ongoing trend as there’s a high divorce rate among them. Their life is very hard.”

Work aside, the truly new development, according to Ventura, has been in tourism. “Five years ago the Abe administration liberalised the visa policy for South-East Asian tourists. Now, we can travel freely to Japan and, to my surprise, about 200,000 Filipinos visited Japan last year.”

We finish our tour in nearby Odori Park, where Ventura used to buy second-hand stuff at the Sunday flea market. “Even here everything has changed,” he says. “The trees that used to stand in the middle of the square have been removed, and the place now looks much better.” Indeed, the current park looks very different from the ugly place Ventura had described in his book.

While heading back to the station, Ventura reflects on how things have turned out for him and the Filipino community in Japan. “Currently there are about 300,000 Filipinos. These are the official figures, but many of them married Japanese nationals so their children are not counted as Filipinos. If you include them, I’d say we’re closer to half a million. We can also invite our families to Japan. So our community is integrating more and more. We not only stand out less than before but we’ve become part of the local community; we’ve been assimilated, and many of us are actually applying for Japanese citizenship. Moreover, our children have become “invisible” i.e. they’re not treated as foreigners anymore.”

JEAN DEROME

Leave a Reply