In this far northerly region, where winters are harsh, ghosts of the past can sometimes change the course of a journey.

When I first set off to the port city of Abashiri in the northeast of Hokkaido, to admire the drift ice that floats across the Sea of Okhotsk from February onwards, I didn’t expect that this trip would lead me to follow in the footsteps of the legendary actor Takakura Ken, a.k.a. Ken-san. This famous actor died in 2014, leaving a lasting impression on Japans northernmost island where his memory still haunts many places. It all started on the platform of Sapporo Station where I had to catch the Okhotsk Limited Express train. As I was about to step on board, I noticed the stationmaster approaching in his midnight-blue coat. “Poppoya!” I almost cried out loud. His posture, his serious demeanour and the way he wore his hat immediately reminded me of the poster of the film Poppoya, which depicted Ken-san wearing a very similar garb. The only small difference was the weather. Takakura’s character had been in the middle of a snow covered platform, whereas this modern day “Poppoya” was sheltered from the snow in the imposing new Sapporo station building. I was on the verge of approaching him to ask if he had seen the film, which was directed by Furuhata Yasuo in 1999 and adapted from the novel by Asada Jiro. However, Japanese trains always leave on time and I couldn’t risk missing it, so I told myself that this apparition was a good omen for a beautiful day and that it would provide food for thought during the 5 hours and 20 minutes of the journey to Abashiri.

Little did I know when I boarded the carriage, that another surprise was waiting for me inside. In the seats just in front of mine, four men had sat down. Ordinarily it would be rare for travellers on a train to attract my attention, but there was something unusual in their demeanour. It didn’t take me long to realize that the two men seated next to the window were prisoners being escorted by two plainclothes policemen, and that their final destination was the same as mine, the town of Abashiri or more accurately the infamous Abashiri prison. Having barely recovered from the shock of seeing Poppoya’s reincarnation on the platform, within a few minutes I found myself once again immersed in the world of Ken-san. I’d not imagined that the journey would take such a turn, but it seemed that Takakura Ken would be the guest star throughout my trip. In fact, the two prisoners were handcuffed in just the same way as Ken-san had been in Abashiri Bangaichi, a film released in 1965 which made him the indisputable star of Japanese cinema. In one of the opening scenes of the film, he appears in exactly the same situation as the men sitting before me. As wi-fi was available for most of the trip, the idea of buying the film on iTunes and downloading it popped into my mind, so that I could remind myself of the story and the scenery that Japanese audiences enjoyed at a time when Hokkaido was still a distant and hostile land.

Nowadays, tourists don’t hesitate to visit this part of Japan where the weather is still harsh, especially in winter, but which still offers landscapes of unequalled beauty. Today it is much easier to get there than it had been in the past, and since the establishment of low-cost airlines such as Skymark, travellers largely prefer to fly. The opening of the first section of high speed rail between Shin Aomori at the far north of Honshu and Shin Hakodate at the south of Hokkaido means Tokyo is now little more than 4 hours away by train. When the line is completed in 2035 it will be possible to get to Sapporo from the Japanese capital within 5 hours. The inauguration of the Seikan tunnel between Honshu and Hokkaido in 1988 has really opened up this large northern island. In his own way, Ken-san also took part in that adventure by playing the character of a rail engineer, Akustu Tsuyoshi, in the film Kaikyo (The Strait), directed six years earlier by Moritani Shiro and dedicated to this giant underwater project.

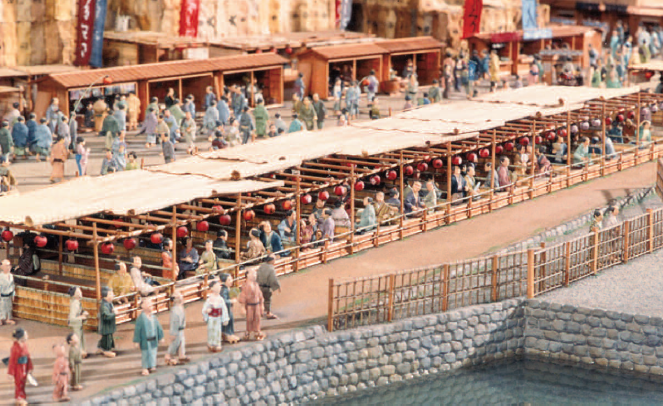

From outside, nothing suggests that this prison was once considered the “Hell of the North”, but a short visit inside swiftly proves otherwise, especially in the part built in 1912 to plans inspired by the starshaped prison in Louvain, Belgium. It did not require large resources for surveillance, as an ingenious system of bars enabled guards to look into the cells without prisoners noticing. Comfort was Spartan at best, with 3 to 5 convicts incarcerated together in a rather small space, which often led to fights such as the ones seen in the Abashiri Bangaichi films. There were also a few isolation cells, but prisoners actually spent fairly little time inside the prison, as can be discovered in the exhibition rooms set up in the other buildings. It’s quite obvious that convicts had to to undertake particularly difficult hard labour in an extremely harsh environment. In the 1965 film we see men felling trees in the snow, but even that is a less severe punishment compared to the tasks that the first prisoners were forced to carry out at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. The construction of the prison came at a time when the Japanese government had embarked on the large scale development of Hokkaido, previously a totally neglected area. Infrastructure was required, including roads to encourage pioneers from the mainland to settle there. One of the exhibition rooms tells the story of the work carried out by a thousand inmates to construct 160 kilometres of roads. More than 200 of them lost their lives due to the inhuman conditions in which they were made to work

It’s understandable why some wished to escape, but Abashiri prison had a reputation for being a place from which nobody could leave. Yet some, like Nishikawa Torakichi, never stopped trying — he made six recorded attempts. However, just like Takakura Ken in Abashiri Bangaichi, he actually managed to get out of the prison complex but was then confronted with hostile conditions, especially when attempting to flee in winter. Ken-san was eventually released from prison, walking through the front gate in the springtime into another film, the greatest of his career: Shiawase no Kiiroi Hankachi (The Yellow Handkerchief). Released in 1977 and directed by Yamada Yoju, this feature film confirmed the special relationship between Ken-san and Hokkaido. In it he encouraged a whole new audience to come and discover the beauty of this region at other times of the year, not just winter.

However, before heading off, I decide to spend a night at the inn run by Matsushita Shinji, about fifteen minutes away from Abashiri station. It’s called Kagariya and is located on the shore of Lake Notoro, which in winter becomes a vast expanse of snow and ice. This ryokan has a large communal bath, but also several rooms with a rotenburo (outside bath), into which one can slip with pleasure after a day spent out in the cold. The greatest delight has to be the food though. It is possible to discover many of the local specialities here, things like crab with giant oysters, pink salmon and rockfish, tasty fare with a reputation that has spread far beyond the city itself. To accompany these delicious dishes I recommend the Blue Ryuhyo Draft, a light beer with a rich flavour. The first sip takes me back to Ken-san’s world, where in one of his first scenes in Shiawase no Kiiroi Hankachi he drinks his first beer after his release from prison.

The memory of Takakura Ken still haunts me, and I need to go the whole hog to thank him for having been my travelling companion and for giving me so many years of immense enjoyment on the silver screen. I check out of Kagariya early the next day, after a breakfast worthy of a starred restaurant, and take the train again, but this time in the opposite direction. Before leaving, I download another film: Eki (Station), which in my eyes is one of the more emotional films starring Ken-san, as well as the fabulous Baisho Chieko as the owner of an izakaya. This feature film, again directed by Furuhata Yasuo, will help me while I’m waiting at Fukagawa, to change to the Rumoi line in the direction of Mashike. Made in 1981, part of the film was shot in this little harbour, but I discover that the Japan Railway Hokkaido company closed down the station on 20th of December 2016 as it was not cost-effective. Yet I’m told that there are many tourists like me who came to Mashike station in search of Ken-san. Not enough, clearly. Nevertheless, the town council has decided to dedicate a small amount of its budget to the maintenance of the building in Ken-san’s memory, similar to Ikutora station on the Nemuro line where Poppoya was shot. So I take the train to Sapporo once again, with the hope of coming across the man who disrupted my journey in the far north in such a delightful way. Alas, when I arrive in the early evening, the platforms are deserted. Outside, the snow is falling heavily. At the end of the platform, where there’s no roof to shelter from the snow, I notice a figure in the gloom. Could it really be Ken-san? Fearful of being disappointed, I retrace my steps, keeping the image of Takakura Ken in my mind, as he looks up while waiting for the train to arrive.

ODAIRA NAMIHEI

Leave a Reply