Ozu Yasujiro’s favourite actress, who died in 2015, left her mark both on the history of cinema and on Japanese society.

Ozu Yasujiro’s favourite actress, who died in 2015, left her mark both on the history of cinema and on Japanese society.

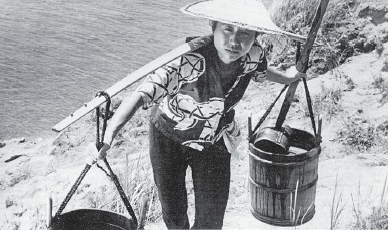

Tourists on their way to a nearby Buddhist temple walk past a Japanese style house, almost completely hidden by a high bamboo hedge. Situated around two kilometres from Kamakura city-centre, the former capital of Japan, this little corner nestling on the side of a hill is far from the hustle and bustle of the city. The visitors who take selfies outside the main pavilion appear not to know about the legend who lived here. Hara Setsuko, the shining star of Japanese cinema and best known for her films with director Ozu Yasujiro, is a legend, a myth and a mystery. She spent the second-half of her life in this house, in complete seclusion, after she retired in 1963, right up until she died on the 5th of September 2015, aged 95. Many insensitive photographers and prying admirers tried to pierce the thick bamboo walls in vain, but all requests were swept away with a brush of the hand. Her nephew, who was the link between Hara and the media, gave the same answer for decades: “I’m sorry, she does not give any interviews”. An absolute silence was maintained until her death and even that was not revealed until nearly two months later on the 25th of November.

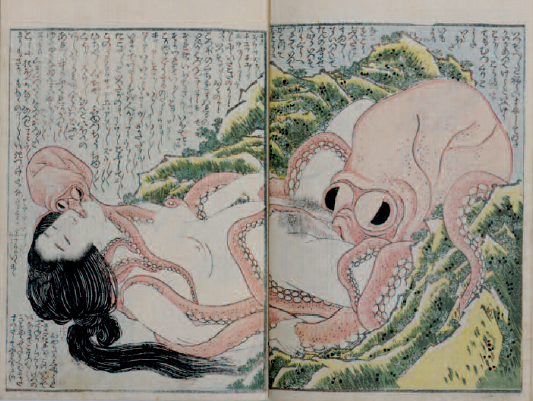

This half-century spent as a hermit in her Kamakura house reinforced the myth surrounding the actress, and was in complete contrast to her dazzling career throughout the golden age of Japanese cinema. Born Aida Masae in 1920, her dream was to become an English teacher, not an actress. “Cinema seemed like a foreign world to me, it was too ostentatious,” she said, but her arched eyebrows, her snub nose and her fair skin had inspired her brother- in-law, who was starting to make his way in the cinema as a director. He was convinced of his sister-in-law’s talent and suggested she should become an actress. His certainty, and her family’s financial difficulties, led her to leave school aged 14 and join her brother-in-law’s film company in 1935. Though this young girl had no idea about what was awaiting her, those around her and the public were quick to notice her unique skills. At the time it was said that her elegant eyebrows and nose, her deep set European eyes and her old-fashioned smile proved that her grandfather had German antecedents. No member of her family ever raised this topic publicly, but it was “a possibility”, said Chiba Nobuo, film critic and an expert on the actress. There’s no longer any way to prove these claims but one thing is certain; at that time the Japanese saw the actress’ western appearance as a reflection of modernity. This is an ironic paradox, as in Europe she was considered to be the epitome of a Japanese woman – discrete, respectful and submissive towards men. After several supporting roles in some ‘talkies’, she played the heroine in The Daughter of the Samurai (Atarashiki tsuchi, 1937) with the German director Arnold Fanck, a cultural and diplomatic attempt to bring both countries closer together. Hara plays the role of a young Japanese girl, candid and innocent, who awaits the return of her lover who has left to study in Germany. The latter, realising how attached he is to his native country, breaks up with his German girlfriend and returns to marry the young Japanese girl, with whom he leaves for Manchuria. Despite the many Japanese clichés, the film became a huge success. Over 6 million people went to see it in Germany, and admire what they referred to as “this typical woman belonging to this proud race”.

The team even travelled to Europe to promote the film, where crowds, smitten with this new star, massed to welcome her at Berlin railway station. She posed for Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, who said he found the film “useful to understand Japanese culture”, but also “too long”. After the war, Hara confessed that she was “too young” – at 16 years old – to understand the dark side of the film’s political context. Nevertheless, “It’s thanks to this film that directors noticed Hara’s talent, someone with a western appearance capable of playing the role of a traditional Japanese woman,” says Chiba Nobuo. “She knew how to find a balance between modernity and tradition in the characters she played,” he adds. Throughout her career, Hara’s image oscillated between these two poles, much like Japanese society at that time, which was about to fall into a fatal war before rising from the ashes transformed into a democratic regime. However, these elements of modernity demonstrated by Hara were neglected, even suppressed in the dark years following her visit to Europe. During that period she only played traditional Japanese female roles, as in The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (Hawai-Mare okikaisen, 1942), filmed during a time of censorship, in which she plays the role of the sister of a soldier who takes part in the attack on Pearl Harbour. She encourages him to go to war and to fight bravely for his country, just as all Japanese women were expected to. All good things come to an end, but so do bad ones too, and Hara’s talent blossomed with the end of the war. Her image echoed the needs of post-war Japanese society, which needed a star to represent the new, young, free and dynamic era, and which was dominated by the rejection of militarism and a yearning for democracy. Then aged 25, this beautiful and dazzling woman was able to rise to the challenge. She joyfully drew on her talent as if she, herself, were celebrating freedom. “We Japanese have been oppressed and exploited like slaves for such a long time. As a consequence, we’ve never had our own identity. Freed by the end of a nightmarish war, now we are blinded by the light of freedom.” is the stirring line that she cries furiously in The Blue Mountains (Aoi sanmyaku, 1949), in the role of Shimazaki Yukiko, a middle-school teacher opposed to her patriarchal superiors. The audience, taken aback by this “modern” star who had become an icon of for young people, called her “The muse of Japanese democracy”.

That same year she worked with the reputed director Ozu Yasujiro for the first time. He had wanted to work with Hara for a long time, and gave her the role of a refined young woman called Noriko in a series of three feature films. The last one, Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, 1952), immortalized their names in cinema history. Ozu describes the decline of the Japanese family system as experienced by a couple of pensioners. Hara, 33, was at the peak of her career, and played to perfection the part of their daughter-in-law who treats them kindly during their visit to Tokyo, unlike their neglectful children. The director tackled universal themes – such as generational change, ageing and death, tradition and modernity – with the precision of a watchmaker. As for Hara, she personified a war widow, loyal to family traditions and refusing to remarry despite the custom. Critics see it as a reflection of Japanese society at that time, which was on the lookout for new traditions as the country started to grow economically and aspired to become democratic. “Ozu tried to combine both these ideas in the role of Noriko, and nobody but Hara could have played the part. Nobody,” says Chiba. The intimacy between the actress and the director led to rumours that they were lovers. Whether that’s true or not, she didn’t wish to interrupt her career to get married, and remained single all her life. This rebellion against the custom of the time – a custom which is often still still upheld today – led to her nickname of “The eternal virgin”, although Hara herself strongly disapproved of it and denounced it as “a media invention”. However, the roles she was given became more and more limited; too old to play a young girl, yet too famous to be an extra, she slowly lost her dominant position in the cinema.

The audience turned their attention towards new stars and the sexist habits of the film world left no room for a 40-year-old actress. Tired of being followed by tabloids, suffering from cataracts and maybe aware of the limitations of her career, she decided to bring that career to an end without a public announcement. However, her disappearance from the screen only fuelled the legend. She could finally spend the second half of her life in a way she had long desired to, living in tranquility in Kamakura, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, a city that must have been full of memories for her from the times she worked with Ozu there. According to Hara’s nephew she liked to read the newspapers and talk about international news, from the rise of ISIS through to climate change. Her reputation and image as an icon of femininity were never tarnished during her retirement, but society changed a lot during that half-century. Seventy years after “the war that afflicted the youth” of Hara Setsuko’s generation, the country is now taking a new and unknown direction with its ageing population. What did the actress who was called “the muse of Japanese democracy” think of it? We will never know.

Yagishita Yuta