The world famous musician’s interest in Japan and the connections he forged helped create his legend and international renown.

The world famous musician’s interest in Japan and the connections he forged helped create his legend and international renown.

In front of David Bowie’s childhood home, 39 Stansfield Road, Brixton, London, numerous mourners placed flowers, candles and messages. Among them is a message from Kanako, wrapped in plastic to protect it from the rain. It starts in English with “Dear David Bowie” before continuing in Japanese “出火吐 暴威様”… Kanako chose to write the name of the musician, who died on the 10th of January 2016 at the age of 69, in Chinese characters, just like the designer Kansai Yamamoto did over 40 years ago on the stage costumes he designed for him. “One who vomits fire and violently spits out words” is a near literal translation of the chosen characters used to transcribe the name of the artist who was greatly inspired by Japan at the time. “I think it’s the only place I could live outside England,” he said in an interview published in the British magazine Melody Maker on the 24th of February 1973. He had not yet given up on his Ziggy Stardust persona, which borrowed many elements from a world influenced by Japanese culture. His Aladdin Sane tour ended in London a few months later and, wrapped in his cape with the red and black kanji signalling his interest in the Land of the Rising Sun to the audience, he would announce the end of this important phase in his career. At the time, the singer had imagined building an installation in the Japanese archipelago and, although he never did, Japan was a dominant factor in the first few years of his artistic career, up until the start of the 1980s. Just like other artists a century before him, David Jones, aka David Bowie, turned to Japanese art as it expressed something new and different to which he aspired. He could have made the Gongourt brothers words his own: “Art is not one, or rather, there is not just one form of art. Japanese art is as great as the Greek’s. And what is Greek art in truth? Beauty in realism. No fantasy. No dreaming”.

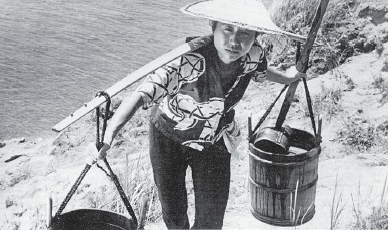

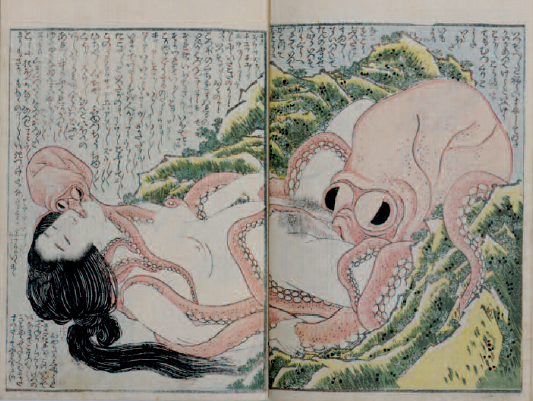

David Bowie wanted to be free from the artistic shackles of his time. On the lookout for new trends before they became fashionable, the future Ziggy Stardust understood that Japan could help him express his creativity and emphasize what was unique about him. The time was right, with this former wartime enemy once again accepted and held in esteem within cultural circles in England, and several exhibitions of Japanese art taking place in the British capital. In the fashion industry, patterns from the Far East were starting to make their way onto the catwalk and bunraku and kabuki shows were in the theatres. David Bowie was smitten. He took lessons with choreographer Lindsay Kemp, who had been greatly influenced by Japanese dance, music and classical theatre. “I taught my approach to Japanese dance, and we would practise to music by Takemitsu Toru,” he recalled. There’s no doubt that he helped his student make use of some the elements of this art in his stage shows that turned the music world upside down at the start of the next decade. “I believe he knew nothing about Japanese theatre before we met. He knew lots when he left,” the dancer recalled. The meeting between David Bowie and Yamamoto Kansai is also crucial, as it underlined the influence of Japan on the artist and gave him the opportunity to assert the sexual ambiguity of his characters. At a time when these kinds of experiences were being questioned by a society searching for change, David Bowie drew on Japanese influences, especially from the realm of kabuki, in order to embody characters that called into question the established order in regard to sexuality. The onnagata, men who played female characters in the kabuki theatre, fuelled his imagination. Yamamoto Kansai worked alongside Bowie and created costumes perfectly tailored to his needs.

“He had an unusual face. He was neither man nor woman. Which suited me perfectly as most of my creations were designed for either sex”, explained the man who provided the singer with some of his most original costumes for his famous tours in 1973 and 1974. Ziggy Stardust is “like some cat from Japan…” sings Bowie in his famous song. Though he abandoned Japanese outfits in 1973, he kept in touch with the Land of the Rising Sun, whose influence continued to permeate his work. He worked on several projects in collaboration with the photographer Sukita Masayoshi, who took some of the best portraits of Bowie. Japan was also a source of inspiration for his songs, as the lyrics testify. In Blackout, the fifth track on his album Heroes (1977), he declares that “I’m under Japanese influence/And my honour’s at stake”. Two years later he mentions the city of Kyoto in Move On, his third song on Lodger. The following year, in the song Ashes to Ashes from the album Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), it’s “Just pictures of Jap girls in synthesis” that seem to haunt him. With this song, he appears to want to close this chapter of his life that is marked by excess, perhaps connected to a search for identity. He’d started his career by plunging into the world of Japanese culture and finished it symbolically with his role as Major Jack Celliers in the film Furyo (Senjo no Merry Christmas, 1983), directed by Oshima Nagisa. The ambiguous relationship he has with Captain Yonoi, played by Sakamoto Ryuichi, in many ways recalls the time when David Bowie played with sexual ambiguity using what he had learnt from kabuki. But unlike the previous decade, his character, who actually dies in the film, reveals his strength and expresses a turning point in the way he wishes to present himself. At the same time Furyo appeared on screen, David Bowie the musician released Let’s Dance, an album not about Japanese girls, but a China Girl. In the following years Bowie’s image became more masculine than ever as he cast off all costumes inspired by the Far East. He started a world tour during which his fashion became morewesternized, one could say even normal. Maybe even a little too normal, according to some. Could this explain why the tributes from some of the artist’s biggest fans after he died nearly all refer to his “Japanese” phase? Whether they line up in front of the house where he was born, or the mural on Morleys department store in Brixton where a portrait of Aladdin Sane has been painted, this particular period of his career is one that his admirers refer to more than any other as they bring photos and drawings depicting that era. We can also understand why Kanako travelled all this way to “express her gratitude from the bottom of her heart”. “Hontoni arigato gozaimasu,” she writes simply. We share her thoughts.

Article and photo: Odaira Namihei