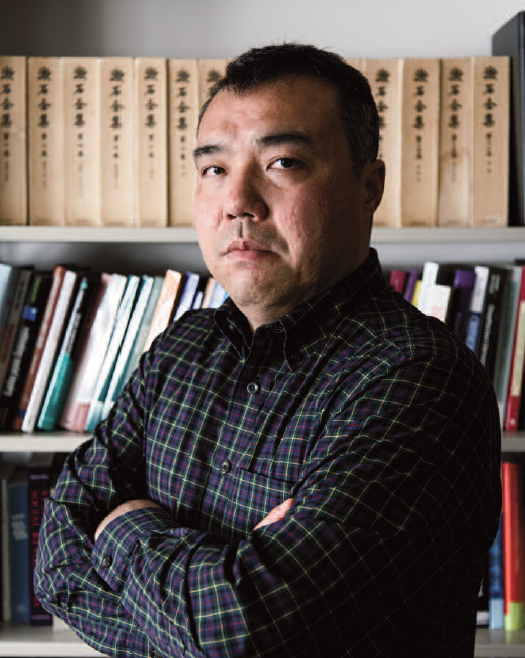

The director speaks to Zoom Japan at the screening of his film at the Raindance Film Festival..

What are the main highlights that we should we look out for in “Obon Brothers”, your film that’s being shown at the Raindance Film Festival?

Osaki Akira: There are many things in it, but I think it’s a bit embarrassing for the director himself to talk about it in that way. What I mean is, this film reflects some of my own personal experiences, as it’s the tale of a director who shoots a film; but it does not go well for him and he can’t do a second one. So it’s pretty much all about me. Having said that, well… it’s not exactly about the film director himself, but portrays the people around him, such as his family and friends, and how they get up to all sorts of things, although nothing really major actually happens. Hmm, I guess I’m not really making it sound all that appealing saying stuff like that. So it’s not a film that shouts loudly about how people live their lives. It just depicts good but awkward people from the countryside in a matter-of-fact way, people who are connected to the kind of small everyday theatre you could find anywhere. And it’s the kind of film that gives you a little bit of courage in the end, which makes it very appealing (laughs).

Were there any amusing episodes while making the film or anything that was a particular struggle to do?

O. A.: There were probably some struggles with the film’s content as well, but seeing as it took 7 years from doing the initial planning to actually filming it, I’d say that the biggest struggle was how we had no money and had to work out how to make it all possible in the first place. Although we did manage to make it a reality in the end.

The entire movie was filmed in Gunma prefecture, so what was the big appeal of that area?

O. A.: Gunma is around 100km north of Tokyo and is almost entirely fields and rice paddies. Basically, it’s the rural part of the Kanto region. But all the people there are really great, good people. The towns there don’t have many particularly stand-out characteristics, but the one town we featured in the film is surrounded by amazing picturesque landscapes, including the three mountains of Mt. Akagi, Mt. Haruna and Mt. Myogi. It’s a really plain and simple rural region, but very beautiful, and the people there are just great. How I came to know that was because while I was filming, there were so many locals who volunteered to help out, and they all loved Gunma. In some way I think that they picked up on my feelings about making this picture and wanted to help out. I think that wherever you go, one of the best things about country people is how they’re always so kind and can always come together as a community to achieve something.

What is your impression of British audiences?

O.A.:Well, we’ve not quite started screening the film for British audiences yet so I am not really sure, but I certainly feel that there are a lot of people

here who appreciate cinema. I get the impression that they are very knowledgeable about films.

Who is the film director who has had the most influence on you?

O.A.: I think I’ll say Mr Kitano Takeshi (laughs). There are several others too, such as Suwa Nobuhiko, Kuroki Kazuo and Anno Hideaki, but those guys are all my contemporaries who have been in the industry longer than me and have worked together with me on projects before. But ultimately, I’d probably say it was Mr Kitano and Mr Suwa that have influenced me the most.

What is your absolute favourite cinematic work?

O.A.: That’s a difficult question to answer if you have to narrow it down to just one! If I take it as just one film that I liked or influenced me most, then I remember seeing Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” when I was 20 years old, and that influenced me greatly. Not really in how it was made but in its sheer impact; the impact on me when I first saw it was amazing. It was the scene where Malcolm McDowell had his eyes clamped open and he was being shown violent video footage. When I saw that scene it stirred a memory, as though I had seen it somewhere before. Thinking hard about it, I remembered that there was something like it in the manga of Tezuka Osamu and that it reminded me of that. But as a film it was a very high quality production and used all kinds of different music and things, so I was very surprised by it and I think it must have influenced me. If I were to give one more example then I would have to say the old black-and-white Japanese films “Humanity and Paper Balloons” (Ninjo Kamifusen) and “The Million Ryo Pot” (Hyakumanryo no Tsubo) by Yamanaka Sadao. Those two were both incredibly interesting works, but if I had to choose one over the other then I’d pick “Humanity and Paper Balloons”.

I hear that this is your first time in London. What are your impressions so far?

O.A.: I heard that there was a law that prevented buildings being modernized here or something, and wherever you go there are lots of old historical buildings to see. I basically really like those kinds of buildings, so it’s generally very easy for me to get to like the towns here. I have only been here for a day or two, but it already feels very cozy and comfortable.

Please could you provide us with a message for all the readers of Zoom Japan?

O.A.: This is a great year for independent Japanese directors. Not just myself but several other talented guys are also releasing original, new films, such as Tsukamoto Shinya’s “Fire on the Plain” (Nobi) and Ishii Gakuryu’s “That’s It” (Soredake), so please go out and watch them!

Interview by Van Yoshiki