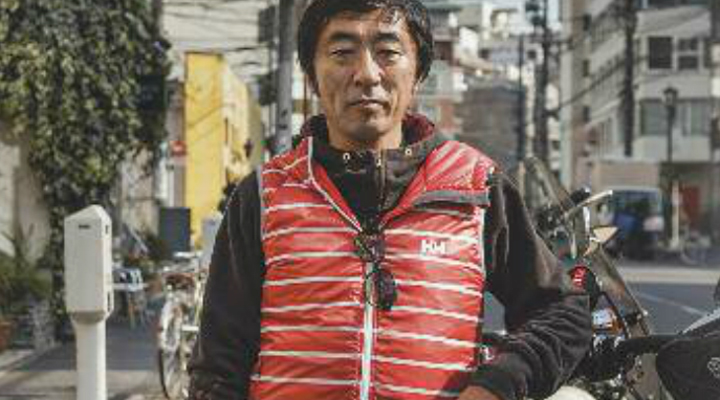

For Ikeda Shin, who’s passionate about Harleys, motorbikes have been a great means of self-expression.

For Ikeda Shin, who’s passionate about Harleys, motorbikes have been a great means of self-expression.

Editor-in-chief of the magazine Hotbike Japan, Ikeda Shin has been passionate about Harley Davidsons for over 25 years. Yet this indefatigable globe-trotter was not always a “biker”. Born 1962 in Nagano, this youthful 50 something, doesn’t look anything like the stereotypical tattooed biker who rides around in a gang. He’s very shy and turned to motorbikes as a means of escape from the already very pressured Japanese society of the 1970s. Ikeda became a motorcycle racing star riding Harleys, travelling across the United States, then Asia as a reporter, before founding the magazine Hotbike, followed by another called Tabigaku, dedicated to incredible travel tales. Now he shares his tales from his own journeys and the people he met on them, from bosozoku to otaku, including some time with the Hells Angels, as well as his vision of Japan from his time as a reporter, a traveller and a biker.

Your love for Harleys led you to publish Hotbike, but before that, what were you doing?

Ikeda Shin: Like all teenagers, I dreamt of having a big motorbike, but my parents forbade it. I was 16. I was passionate about bicycles and when I bought my first Mopetto (Moped), I said to myself: “On this, I can travel to the ends of the earth!”, it was a revelation. After that, I went to Tokyo for my studies. I secretly took the test to get my motorcycle licence. Back then, it was extremely difficult to pass the test, and I had to take it several times. Finally, I bought my first Italian motorbike, a Ducati. I had no interest whatsoever in Harleys back then!

Were you part of a biker gang in Tokyo in the 1980s?

I. S.: No, not at all. In fact, I nearly always rode on my own. I enjoyed the solitude as I was incredibly shy. I couldn’t even go into a restaurant or ask for directions! Riding a motorbike, you don’t need to talk. By the time I was 18, I would head off on my own, with only a sandwich and my sleeping bag. It was sometimes scary sleeping in temples or in parks, but I preferred it to staying in a hotel.

This was in the era of bosozoku, can you tell me more about them?

I. S.: “Boso” means racing, and “zoku” means tribe or gang. That’s what many young bikers did back then when I was in high-school. They would get together in gangs and would race at top speed while zig-zagging to escape the police. They had a particular appearance, with bleached hair and kamikaze style coats, and rode 400cc bikes they had modified to look like Choppers by removing or replacing certain bike parts to make them go faster, look better and make as much noise as possible to wake everyone up! Bosozoku were considered to be dangerous gangsters in Japan, although many managed to lead successful lives later on. Being a bosozoku was first and foremost about a kind of energy. In a Japanese society where there was no place for exam failures, you had to find a way to unwind, to release the pressure from all this stress. I think this is quite unique to Japan. In contrast to the United States, where they have wide open spaces, here there is nowhere for you to escape to when you are young. Today it has become a fashion trend, which has nothing to do with the original spirit of bosozoku.

You first started working for a magazine that specialized in motorbikes. Had you always wanted to do this?

I. S.: I always enjoyed writing. When I left university, I answered an ad in a bike magazine. I loved speed and everything Italian, like the fashion and all of it. But when Harley came out with their first Evolution Sportster in 1986, I couldn’t resist. I had always been passionate about sport and speed. But this bike was still too slow for my liking, so I started to “tune” it, to work on the engine. I pulled it apart at least a dozen times! Back then, Harleys were very rare in Japan and it was really hard to acquire the different parts. But that was how I learned to be a mechanic and it changed my life. From then on, I could do everything myself.

When did Harleys become popular in Japan?

I. S.: It was in the 1990s that Harleys really took off in Japan. Back then, there were more and more bikers getting together for “Sunday Races” – they continue to this day. In the 1980s, when I used to go, it was more of a gathering of vintage bikes. I started interviewing people, then I ended up joining them. I had saved money for a large Harley Chopper, like the one in the film Easy Rider!There was a special race called “Harley class” sponsored by Harley Davidson Japan. More than 1,000 people would enter every year, and after entering several competitions, I managed to win the race.

So were you influenced by films such as Easy Rider?

I. S.: Not at all! In fact, when I was younger I would always fall asleep every time I tried to watch it. I didn’t understand the story about these hippies and their LSD. And I hated the Harley Chopper style too. It’s hard to believe it when you see me now (laughs).

Was it around this time that you first went to the United States?

I. S.: Yes, I’d become mad about old Harley models. One day, the editorial team decided to come out with a special issue on Harleys, and that’s how I first got to set foot in Los Angeles. I had never left Japan until then. I will always remember going through customs. My legs were shaking, and I couldn’t speak a word of English. And later I remember seeing LA and its endless skies and rows of coconut trees speeding past. Every Japanese person of my generation dreamed of going to the United States. After the release of this special issue we had a lot of success and I was able to go back to cover another story.

How did Hotbike Japan come about?

I. S.: I went to visit the offices of Hotbike America. I was very impressed because in Japan you couldn’t find any magazines that were dedicated to Harleys. I returned to Tokyo and I pitched a project to a publisher to set up my own Hotbike magazine. The first issue came out in 1992.

How do you explain the magazine’s continued success?

I. S.: I reckon it’s because writing is at the heart of Hotbike. It’s not about motorbikes, or girls, but about travelling! While reporting on one of the first stories I covered for the magazine, near Santa Monica, I met a Japanese man called Izumi Shirase. He hadn’t been back to Japan in 15 years and he was unlike any other guide we had over there, who usually took us to karaoke bars or Japanese restaurants in Los Angeles! Izumi lived on the margins of society and only hung out with bikers. With his help I was able to gain access to this world. And that was when I realized: “I am not a real biker!”

What is your definition of a biker?

I. S. : The American bikers I met lived and died for their motorbikes. As for myself, I loved fashion, cinema and plenty of other things beside bikes – whereas it was their life-blood. Nothing else concerned them; it was a way of life. Just as in Easy Rider, they were really just losers. But what is astonishing is that in the United States, contrary to what you see in Japan, losers actually enjoy a kind of recognition! I thought that perhaps that was true democracy (laughs).

Are bikers in Japan very different from American bikers?

I. S.: Yes, they have nothing in common. To be a “biker” in Japan is more about fashion. That’s why I am always self-conscious about calling myself a biker. I don’t wear ripped jeans, nor do I have long hair or Hells Angel gear. You don’t need all of that to be a biker! That’s what I explained when I wrote those first articles for Hotbike. Then again, when I first met Hells Angels to interview them, I thought they were similar to the old-school ninkyo yakuza, yakuza who have a code of honour and are ready to kill to defend their brothers! They have a patch divided in three on the back of their jackets, similar in a way to the golden pins the yakuza wear on their jacket collars. The difference is that in Japan the real gangsters drive Mercedes Benz with darkened windows, whereas in the United States, they have long hair and ride Harley Davidsons!

Do the Japanese enjoy riding motorbikes?

I. S. : It’s not as common as in the United States, but I would like to encourage young people to try it out. In my case, I was so shy that the motorbike taught me about life. Because I’d head out alone on the road, I learned how to work things out on my own, and learned how to speak English. I noticed after quite a few years that I could go anywhere I liked. Japanese people are shy at heart, and quite romantic, and that’s why I think that motorcycling is a mode of transport that suits them. It doesn’t matter what kind of motorbike you have or the style of clothes you wear.

How would you explain that there are fewer and fewer bosozoku?

I. S. : The many police crack-downs and anti-gang laws are killing off the movement. Japanese society is becoming more and more sanitized. Everything is now seen as potentially either dirty or dangerous. We even tell children to stop playing with soil, it’s crazy! I also feel it’s in the way language is ever more restricted, as though we’re always afraid of being impolite. It is very tiring and stressful. And this has turned people into paranoid germophobes, what are called kokin otaku in Japanese! And there are more and more hikikomori – those young people who remain confined in their homes for months, sometimes years – and murders committed by kids. When you’re young, you need to let off steam, but I have the impression that society today only tries to suppress it, until one day, the lid blows. I would rather have the bosozoku of my youth, it was much healthier.

In your column, you often write about social trends. What message do you try to convey to your readers in Hotbike?

I. S.: To reflect a bit more. Twenty years ago we bought petrol and spare parts for our bikes, or CDs or guitars with our pocket money. But I’ve noticed that today young people spend all their money on mobile phone subscriptions, and it makes me really sad. It seems as if the phone has become the sole means of communication and relaxation. I’m not sure about Europe, but here, they not only see less of each other, but they hardly speak to each other any more, and just communicate by text or through an online chat-room! We live in a world of instant gratification, with information about everything available just one click away; all the news is made available in a few lines on our mobile phones, but this does not teach us about the real world.

Can the motorbike be an instrument of freedom for those young people who are disconnected with the real world?

I. S.: Yes, motorbikes are all about the real world. Quite the opposite to the fantasy worlds of manga and video games. To ride a bike is to feel the heat of the sun, the bite of the wind and cold, it’s a very physical experience. One day, a young American biker told me that motorbikes ran in his blood, and he had a tattoo on his shoulder that read “Pain is my friend”. It is often hardship that teaches us how to enjoy life. In a recent issue you wrote about your tour around Japan on a motorbike.

Do you think it’s an interesting way for European tourists to discover Japan?

I. S.: It’s certainly an original means of discovering the country in a different way. You might not save anything on the price of a ticket for a high-speed train, as motorway tolls are expensive, but you can drive leisurely along the main roads. From Tokyo to Kyoto, the road runs straight along the coast! For those with smaller budgets, it is very safe in Japan to sleep under the stars in a sleeping bag. Otherwise, there are many good business hotels or “love hotels” that are very fairly priced, and they are an opportunity to experience what it’s like to stay in a Japanese motel! On my Facebook page, I could leave some tips for European drivers who’d like to try them out.

You brought out a second magazine in 2000, called Tabigaku, which means “learning as you travel”?

I. S.: Tabigaku is written by all kinds of travellers. You don’t necessarily need to be travelling as a backpacker, there are many other ways. Personally I was never a big fan of backpacking, as you don’t need to be saving every penny. You can travel on a motorbike, on a camel or even a donkey! Discovering India was a real wake-up call. I felt a hundred times more relaxed there than in Japan! I didn’t need to go through all the polite rituals to ask if I could smoke a cigarette, and people had very open minds. It completely changed my value system and really helped me get rid of my shyness. I could finally go anywhere I needed without being afraid. In the end, after all these years on the road, I realized I had become a biker after all!

Interview by Alissa Descotes-Toyosaki

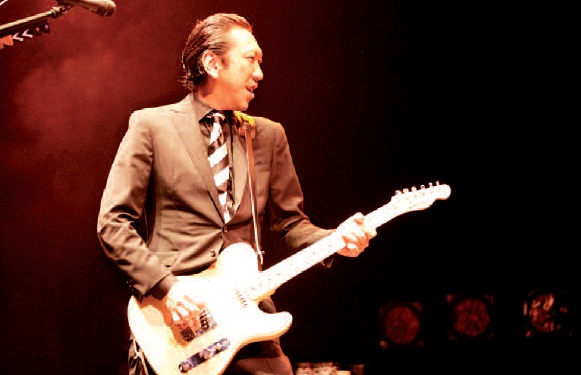

Photo: Photo: Jérémie souteyrat