By following the Kisei line that runs along the coast, you can discover all the treasures of this region, which are more than worth a detour.

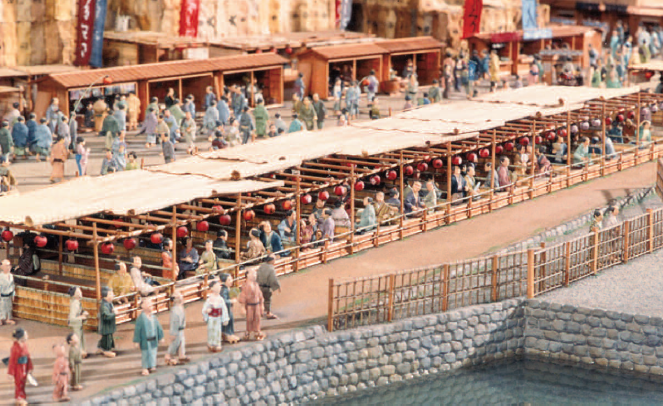

Located in an ideal spot at the far end of a large bay, the charming town of Kii-Katsuura sits in a half circle, reflecting the bright colours on the hulls of numerous tuna boats berthed in the harbour. Proud of its sea-faring traditions, the town provides shelter for a spectacular fishing port and the most lively freshly caught tuna market in the country (open at 7am, except weekends). Some of the specimens are so rare that people fight over them and it is not unusual to see buyers from large sushi restaurant chains paying their weight in gold to buy them up, and then send them in boxes to the big Tsukiji market in Tokyo.

300m from the railway station, on the way to the harbour, there’s a great spot where you can go to relax and bathe your feet. On the outskirts of the city you can also visit a couple of fabulous onsen (hot spring baths) in two large private hotels that are also open to the public and tourists. The first of these, situated at the tip of the peninsular, is Hotel Urashi’a (1165-2 Katsuura, Higashimurogun, Nachikatsura-cho), and appears to be a maze of stairs and tunnels set in a rocky cliff. The baths fit ingeniously inside caves looking out over the sea – a real treat. The second of these hot spring hotels, the Ryokan Nakanishima (Higashimuro-gun, Nachikatsuracho.) enjoys an exceptional location on a private island in Kii-Katsuura bay. To access the island you’ll need to take a private ferry from the jetty in the harbour. Both the indoor and outdoor baths are filled with water from hot springs; the outdoor bath in particular is a heavenly gem. In addition, traditional Kaiseki meals are served in the restaurant if you so wish. On the hotel roof there is a lovely terraced garden with trees, which overlooks the sea. Geothermal hot springs, combined with the beauty of the hilly landscape with its valleys and forests, ensures that this region is a magnet for tourists. The British no longer have a tradition of public hot baths, so many have to be initiated into the rituals of the art of Japanese bathing before entering the pools. First of all, you need to wash yourself carefully with soap in a place set aside for the purpose, then rinse thoroughly with wooden pails of water before setting foot in the bath. In order not to offend anyone, you need to remember that the baths are not there primarily for washing oneself, but mostly to relax, refresh and recharge while enjoying the healing effects of nature.

The water can contain salt, sulphur or iron in differing concentrations and at first some people might feel uncomfortable due to the sulphurous vapours. But don’t panic – there is no danger and you get used to it after a few minutes. The aesthetics of the bathing area are carefully considered, blending harmoniously with stone, wood and plants. One important detail: you’ll need to get used to the idea of bathing in the nude. The most modest of us will choose to enter the pool with a small white towel, placing it on our heads once totally immersed in the water. Male and female bathingare strictly segregated. Finally, do not stay more than 20 minutes in a pool heated more than 50°C. Follow this advice and you will be filled with a feeling of wellbeing that remains with you after you leave the pool. Thirty minutes away from Kii-Katsuura, you’ll find Kushimoto. There are some incredible rock formations at the water’s edge, on the southern extremity of the peninsula by the exit to the small railway station. This strange and harmonious alignment of rocks, known as Hisha Gui Iwa, rises out of the sea and is intimately linked to a local legend.

It is said that once upon a time, the inhabitants of Kushimoto attempted to build a bridge linking the Kii peninsula to the nearby island of Kii-Oshima. However, each time it was built a giant sea creature called Amanojaku would come to destroy it. To help the powerless inhabitants, the eminent priest and holy man Kobo-Daishi, founder of the Shingon Buddhist school, offered his services to build the bridge. The monster Amanojaku allowed the priest to try on the sole and impossible condition that he would have to build it on his own. Amanojaku would give him the strength of a hundred horses and allow him one day and one

night to complete the work, no more no less. At dawn, when the rooster cried, he would have to stop” The famous monk then started to throw large rocks into the sea towards the island of Kii- Oshima. Seeing Kobo-Daishi’s great progress, Amanojaku started to worry. So as to not lose his bet, he decided to cheat by calling out like a rooster before the sun had even risen. Thus the bridge was left unfinished! Only thirty minutes from the station by bus, you can find a more modern bridge built to connect to Kii-Oshima island. The larger island actually breaks off into smaller islands as it goes out into the ocean. There’s a splendid view over the Pacific Ocean from the top of the Oshima lighthouse. On the night of the 18th of September 1890, the large Turkish frigate Ertugrul was shipwrecked off the east coast of Kii-Oshima. It had just left the harbour at Yokohama and was heading to Constantinople. Trapped in a sudden, terrible storm, the crew tried to take down the sails with all the strength they could muster and reach the shelter of Kobe harbour. At the tip of Cape Kashinozaki, which at the time was already marked out by the Oshima lighthouse, the constant battering of the enormous waves broke the frigate’s 40m high mast. The ship, no longer able to make any headway, drifted dangerously and smashed onto the reefs. Water rapidly filled the engine room and Admiral Ali Osman Pasha was left with only one choice before the deck was submerged: lower the life rafts and abandon ship. As a result of the shipwreck, 50 officers and 533 sailors perished, but 6 officers and 63 sailors were saved with the help of the island’s inhabitants and a rescue operation by the Japanese Navy. This event resulted in a rare entente cordiale and sympathetic feeling between both countries. The officers from the Japanese ships that had come to the rescue were received in Constantinople by the Sultan of Turkey and decorated with medals. In 1929, the Emperor himself came to pay homage and, more recently, the Turkish president Abdullah Gül in 2008.

In memory of the tragedy, a cemetery was built next to Oshima lighthouse, to inter the remains of the sailors from Turkey, as well as a memorial and a museum (Kushimoto Turkish Memorial and Museum 1025-26 Kashino, Kushimoto 649-3631). A project is currently underway to salvage the ship and then exhibit it. Following the coastline, you’ll soon reach Shirama (literally ‘the white beach’) bordering the wild sea, with its pure white sand (imported from Australia), contrasting with the numerous contemporary hotel developments, amusement parks and an aquarium situated on the outskirts of the city. The long crescent moon-shaped beach and translucent blue water make this a great place to stop and have a lovely, refreshing swim before continuing to explore this western coast. But be warned, this, the premier seaside resort in the Kansai region, is very crowded at peak season in July and August and almost deserted the rest of the year. Those who enjoy hiking, or who are seeking spiritual enlightenment, should go to Tanabe. The starting point for the millennia old pilgrimage paths of Kumano Kodo (World Heritage listed by Unesco), the seaside town of Tanabe owes its reputation to many small restaurants, food stalls and izakaya. So before setting off in search of the kami (Shinto gods) in the forests of the peninsula, pilgrims can build up their strength by feasting on fish and shellfish. Walking down the main street, it takes 5 minutes to reach the statue of Aikido’s founding father, Ueshiba Morihei, looking out imposingly over Ogigahama beach. In the Kozan-ji temple close by, it is also possible to pause for a moment of reflection at his tomb. You can conclude the outing by walking across charming Kagura Park nearby. The Nakata umeshu brewery (1475 Shimomisu, Tanabe) is 8 minutes away by bus from JR Kiitanabe station, and is well worth the trip. Umeshu (plum wine), famous since the Nara period (710-794) for its medicinal properties and its high concentration of citric acid, is made from plums picked every year in Kishu province in June, when the fruit is not quite ripe. The Japanese created umeshu liqueur in the early years of the Edo period, in order to preserve the qualities of this apricot-like plum. The process to produce the brew starts with preserving the fruit in salt, then rinsing it and macerating it with kori-zato sugar and rice spirit or sake before letting it mature.

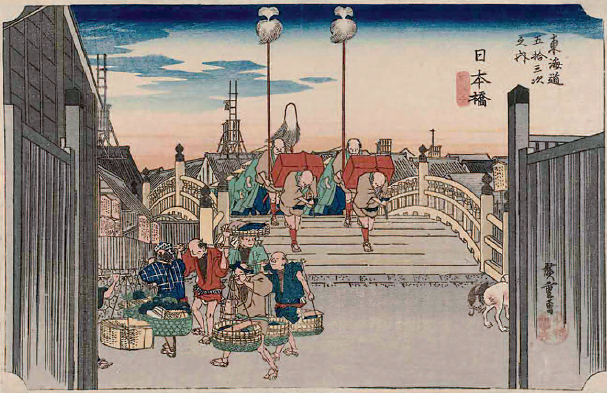

Close by, Yuasa village remains the heart of soya sauce production in Japan. Famous chefs from Tokyo, and even as far as Europe, come here to buy it from the best master brewers still using a recipe that has not changed since it was first brewed 300 years ago. You can visit the soya sauce factory at Kadochi, where the sauce is still prepared over a traditional wood fire. The workshop resembles a large barn built over deep cedar barrels on which the success of the fermentation process depends. Workers stir the liquid by hand on a regular and precise basis, only now and again in winter but more often in summer, blending together the wheat, soya, salt and water. Once filtered and extracted with the help of an old press, the divine nectar is finally obtained: a creamy and fragrant amber coloured sauce called tamari. Even more sought after is the further refined nigori, which can sometimes be found complementing the beautiful grilled fish and vegetable dishes in the best European restaurants. The whole process of making their premium “Kadocho” brand remains a secret despite the widespread consumption of soya sauce in Japan. A small museum across from the factory (7 Yusa-cho Arita-gun) is open only at the weekend; you’ll need to book by calling 0737-62-2035. Our last stop on this journey across the Kii peninsula is Wakayama. On leaving the modern railway station that is part of a large shopping centre, you can escape the urban hubbub and take the bus to Koen-mae, where you can head up to a landscaped area with cherry and plum trees surrounding the city’s famous castle (3 Ichibancho, Wakayama). Built in 1585 at the top of the rocky outcrop of mount Torafu, Wakayama Castle is visible from the whole city, with its charming and strikingly curved eaves and white walls. Its main feature is the complex of buildings called the Renritsu-shiki that includes a three-storey dungeon, covered walkways linking the towers to the dungeon, and two remarkable gateways, one of which is listed as a national cultural treasure. In the 17th century, this fortress held out against the onslaught at the battles of Sekigahara and Kashii (The siege of Osaka).

The original structure was unfortunately destroyed at the end of World War Two, but later restored in 1958. At the centre of the building, in the main courtyard, sits Momijidani, a zen garden with its own private tea house. It’s a jewel that inspires every visitor wishing to learn about the tradition of wabi-sabi and experience true beauty. The Modern Museum of Wakayama (1-4-14 Fukiage Wakayama) is built in a completely different style. It’s contemporary architecture and striking overhanging roofs made up of narrow concrete panels contrasts with the traditional style of the castle only 200 metres away. Its bold geometric lines and the translucence and light of its large interior spaces are the work of Japanese architect Kurokawa Kisho, who also designed the new wing of the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam. Throughout its exhibition rooms, the museum offers a great overview of Japanese contemporary art, with examples of many celebrated local artists including Kawaguchi Kigai, Nonagase Banka, Hamaguchi Yozo, Tanaka Kyokichi and Onchi Koshiro. Paintings by famous international artists are also on display; you can see works by Picasso, Redon, Rothko, Frank Stella and George Segal. One whole floor is also dedicated to traditional paintings, sketches and sculptures from the Meji era (1868-1912).

Manuel Sanchez

Photo: Manuel Sanchez