The matsuri is a communal event which unites all Japanese, whatever their origin.

The matsuri is a communal event which unites all Japanese, whatever their origin.

In his office in the heart of the old Asakusa district Watanabe Takeshi is preparing for the Sanja Matsuri, the three-temple celebration. He has tied a scarf around his neck and over his white clothes he has put on a traditional happi jacket, which represents his street. “Those who have a happi can help carry a mikoshi, a portable shrine. It’s the custom!” he says as he proudly shows off his name sewn onto the collar. Mr. Watanabe is a yakuza, but that doesn’t stop him from celebrating one of the biggest Shinto festivals in the country — just like a million other Japanese — in honour of the Buddhist deity Kannon. “Yakuza have been taking part in the Sanja Matsuri for five centuries, and even if some would prefer that we didn’t we will always be here!” he laughs. He is one of the deputy members of the Sumiyoshi-kai, the second largest organized crime syndicate in Japan, which officially numbers 22. The Japanese mafia, with approximately 80,000 members, benefits from a quasi-official status, as demonstrated in the many films and manga dedicated to them. Nevertheless, yakuza need to remain hidden and their presence isn’t tolerated — except during the matsuri.

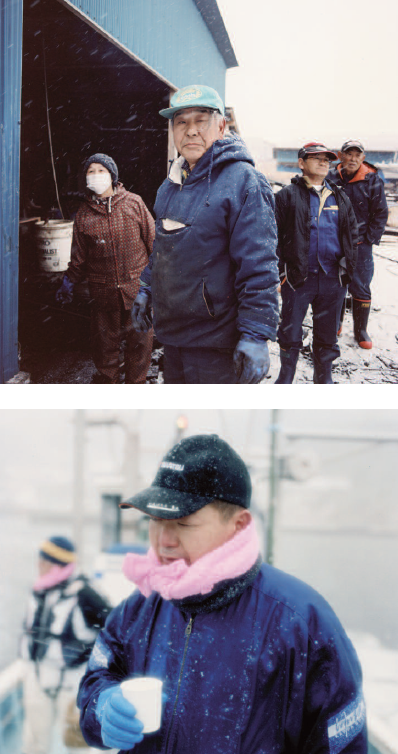

“In the Shinto tradition, the matsuri is a “hare” (ceremonial) day, as opposed one that is “ke” (mundane). Hare are special moments in life when one can draw attention to oneself and come out of the shadows” explains Miyata Junichi, who is a member of a mikoshi association. Carrying the mikoshi has always been an occasion for yakuza and katagi (the underworld term for a regular non-yakuza person) alike to come together. Just like those fairground entertainers and troubadours who enlivened European villages, the origin of the yakuza were tekiya — street pedlars answerable to an oyabun (godfather), who organized the festivities and gradually took control over the violent actions of the underworld. This world is wonderfully described by Philippe Pons in his book Misères et crimes au Japon (pub. Gallimard, not available in English). “Three kinds of people carry the mikoshi: people from the shrine, ordinary people and yakuza. They all come together as an entity, all with the same powerful idea: to honour the represented deity” says Mr Miyata. To illustrate this, a mikoshi carried by both men and women crosses the street followed by a little band of drums and flutes. Guided by a Shinto priest shaking a branch of sacred pine to bless the neighbourhood, the divine palanquin swings up and down to the cries of “Oissa! Oissa!” before stopping outside the office of the Watanabe clan. “It’s a traditional welcome. Some shops, restaurants and businesses offer drinks and snacks to those who are carrying the mikoshi as a symbol of prosperity” explains Mr Watanabe. For the past three days the office front has been transformed into an open air-cafe where children run around collecting sweets and people meet to chat in the spirit of matsuri. “It’s not about bribery, it’s to maintain social balance and solidarity” says one of the Yamasawa Hitoshi clan members. His body is covered with traditional tattoos, called irezumi, and he is dressed in just a simple loincloth known as a fundoshi, but nobody is shocked. “When using all your strength to carry the mikoshi, you need to feel comfortable!” says a man in the procession, feeling the impressive bulge on his right shoulder. Adachi Ken is around fifty years old and has been carrying the mikoshi since the age of five, so he is justly proud of his bump. “Those who have a bump are those who have carried the mikoshi most devotedly” he says. Mr Adachi is a tobi, a type of builder, who participates in the Sanja Matsuri once a year by assembling the mikoshi. The tobi, who wear fundoshi and whose bodies are covered with tattoos, are not part of a yakuza clan but form a class apart in Japan’s very hierarchical society. “Irezumi is an ancient art in the same way as Japanese etching” says Mr Adachi, though tattoos have become synonymous with criminality and are banned in public places such as baths and sports clubs. Only the matsuri allow the display of these indelible signs of non-conformism, but even at the very popular Sanja Matsuri yakuza tend to be discrete and not draw attention to themselves. “At one time yakuza would climb up on mikoshi and would show off their tattoos.

It created a great atmosphere at the Sanja Matsuri, but because of the new laws nobody is allowed to climb up on them now. The pretext is that it is dangerous, but the real reason is because the police want to catch the yakuza” says Yamasawa Hitoshi, for whom the new rules clearly go against the spirit of the festival. In 2006 a mikoshi was damaged, and the following year three people who climbed up onto the Sanja shrine were arrested. The police intervened with loud-hailers, accused those celebrating of “sullying the Japanese tradition” and threatened to stop all celebrations in the district. Following these arrests the police released a statement to Asahi Shimbun that they were starting a new enquiry and accused the yakuza of doing business during the matsuri: hiring out happi jackets at extortionate prices (20,000 yen in order to carry the mikoshi) and accepting bribes from people to climb onto the mikoshi (100,000 yen). The accusations gave rise to a passionate debate on the internet: should yakuza be banned from the matsuri or not? According to some the mikoshi symbolizes a divine being and should not be mounted by any human, let alone a gangster. Others argued that the tradition never banned people from climbing onto the mikoshi — if a mikoshi were to be damaged it was because it was too fragile. Mr Watanabe is of the opinion that this debate reveals that the ties between the matsuri and the yakuza are an open secret. “The relationship is as ancient as that between the police and the underworld” he jokes. He has just welcomed two police officers who are patrolling the area into his office. “It’s just a routine visit to remind you of the rules. No fighting and no tattoos on display” says one of them, drinking from a traditional cup of sake. In the blue light of evening the Watanabe clan converges near the departure point of the large mikoshi from the Asakusa shrine. Hundreds of men are sitting on the ground, relaxed and waiting, with tattoos partially visible from behind their happi. The police have formed tight rows along the avenues and repeatedly call for calm through their loud hailers. All of a sudden a man jumps up and runs towards the mikoshi. Yakuza from opposing clans grab hold of each other, let go, then grasp hold of each other again, in turn pulling menacing or scornful faces. It’s hard to know whether this is account settling or just theatre, but the scared bystanders stick close to the walls, so as not to be crushed. The lucky ones — men and women who have managed to get away — are approaching the sacred shrine, now already at some distance and floating away like a boat on a human tide. Surfacing from the crowd, Mr Watanabe wipes the sweat from his face. He has been carrying the mikoshi and he stops for a few minutes, observing his henchmen whose loud swearing adds atmosphere to the procession. “We can’t disappear, we’re part of Japanese culture!” he says while posing for a picture with a Shinto priest.

Alissa Descotes Toyosaki

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat