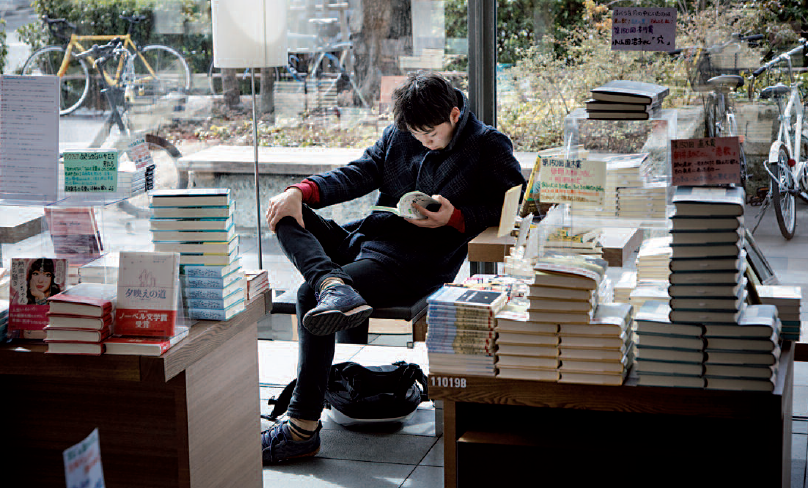

To celebrate our thirty-first issue, we would like to invite you on a journey of discovery into 31 books related to Japan.

To celebrate our thirty-first issue, we would like to invite you on a journey of discovery into 31 books related to Japan.

There are many sources of information about Japan at your disposal. First and Foremost, there’s Zoom Japan, bringing you the latest news about all aspects of Japan every month, but besides your favourite monthly magazine (at least, we hope it is), the media generally does not take a great interest in Japanese current affairs. The land of the Rising Sun usually only gets mentioned in the event of a disaster, or when something important happens in the economic sphere. The Nikkei index 20,000 point threshold captures the interest of many newspapers, as do the management difficulties encountered while dealing with the Fukushima dai-ichi nuclear crisis. Apart from these issues though, news articles or reports about the archipelago are rare these days, but there was a time when Japan and the Japanese were of great interest to everyone. They once dominated the world economic stage, as Japanese companies conquered international markets with their products and the yen was strong enough for them to invest throughout the world. The media produced reams of information – not always very well informed – about this strange country that was sometimes seen as a source of disquiet. We need to accept that time is long past, but having said that, the growth of the Internet has made it a lot easier to access a great deal of previously unavailable information, allowing people to broaden their knowledge of Japan and the Japanese. However, many of these sources still need to be translated so that they are accessible to those who don’t speak Japanese. This explains why books are still very important. At a time when there are fewer people reading due to the rise of digital information platforms, it is good to remember that books are still an essential source of information about Japan. Over the past twenty years, it has not just been scholarly studies about the country, its culture, history and society that have become widely available in translation, but also but also many literary works and comics too. Publishers have achieved a great deal on this front, exploring new literary horizons after previously limiting themselves to certain authors such as Mishima Yukio or Kawabata Yasunari. Of course, it took a great success like Murakami Haruki to prove you don’t have to be a Westerner to be a writer capable of seducing a wider audience. Through Murakami’s work with its universal message, readers have discovered Japan and its society, and have gone on to immerse themselves in the work of other writers such as Ogawa Ito and Higashino Keigo. These two novelists have clearly captured their audiences with their sublime writing styles, but also because they share key insights necessary to the understanding of their country. The same can be said about many famed mangaka, whose work is also highly regarded. Mizuki Shigeru and Umezu Kazuo have both opened their reader’s eyes about new ways of looking at Japan. So to celebrate this wealth of literature, we have selected 31 books about Japan, written by both Japanese and non-Japanese authors, to introduce to our readership. We consider these as some of the best books to help you understand what Japan is all about. Of course, there were many more we could have included, but you have to draw the line somewhere. They are numbered, but in no particular order, so feel free to just dive in with any that take your fancy. All that remains now is to wish you a enjoyable and enlightening read.

Jean Derome and Odaira Namihei

1. 1949 Mishima Yukio Confessions of a Mask Penguin Classics, 2008

Although it takes place during WWII, Mishima Yukio’s second novel explores themes that are still important in Japanese society to this day, such as people’s struggle to fit into a society where those who are different are often ostracised. This was even more true at a time when the authoritarian regime was suppressing any kind of dissent or unorthodox behaviour, such as the protagonist’s homosexuality. So the mask of the title stands for the kind of public image he presents to the world, in the belief that everyone had no choice but to hide their true feelings and take part in a universal masquerade.

2. 1958 Inside and Other Short Fiction : Japanese Women by Japanese Women Kodansha International

This provocative anthology features eight short stories written by female writers. It is a thought-provoking introduction to feminist literature in Japan and the reality of Japanese women’s lives today. Often graphic in style and explicit in content, these stories tackle such topics as marriage, prostitution, reproduction and friendship between women. Many of them highlight the fact that, though increasingly independent both socially and financially, many women in Japan are emotionally and sexually starved, and are still very insecure in their dealings with male-dominated society. Single women in particular are left in the unenviable situation of having to choose between a career and a family life.

3. 2003 Richard Connaughton Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear : Russia’s War with Japan, Cassel, 2004

This book is a detailed study of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), the first war ever won by an Asian country against a European power in modern times. While little remembered in history books, the conflict put Japan on the world geopolitical map and turned a possible colonial victim into an increasingly greedy aggressor, whose future foreign policy would lead to far bigger and bloodier wars in China and the Pacific. Connaughton is a military historian, but he knows how to keep the reader interested, while still loading his narrative with lots of statistics and official reports. This is a useful book to understand the path Japan took to glory and tragedy in the 20th century.

4. 1962 Abe Kobo The Woman in the Dunes trans. E. Dale Saunders Penguin Classics, 2006

Abe was a master of the surreal existential novel, and this Kafkaesque parable, set in Tottori’s miniature desert, pits modern civilized Japan against its old tribal self. An amateur entomologist who ventures among the dunes and gets trapped at the bottom of a crevasse tries in vain to escape, while the village woman who becomes his companion passively accepts her own fate and willingly sacrifices her life for the good of the community. It is this character who stands out far more than the petulant scholar, displaying strength and resilience and how happiness can be found in a seemingly subordinate existence.

5. 1998 Will Ferguson Hokkaido Highway Blues Canongate books, 2003

One day, Canadian English teacher Will Ferguson bet his friend that he could hitchhike the whole length of Japan, and in order to make it more interesting he decided to follow the “cherry blossom front” that sweeps up the archipelago every year, from south to north. What follows is a picaresque adventure along the streets of Japan, full of weird and moving encounters with all sorts of people. Less elegiac and literary in tone than Alan Booth’s and Donald Richie’s works, this insightful and witty book actually teaches the reader many things about Japan and its people without ever taking itself too seriously.

6. 1965 IbuseMasuji Black Rain trans. John bester Kodansha america, 2012

The tragedy brought upon people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki went far beyond the atomic bombings, as the survivors were ostracized for being impure after suffering radiation poisoning. Ibuse’s novel chronicles a young survivor’s struggle against prejudice as she attempts to lead a normal life and get married in the face of rumours that she is damaged goods. Based on interviews and notes from actual survivors, and written in a detached documentary style, the book is a faithful portrait of everyday life in postwar Japan and is even more topical than ever since Fukushima’s nuclear disaster renewed the old cycle or fear and superstition.

7. 2008 Tatsumi Yoshihiro A Drifting Life Drawn and Quarterly, 2009

Japanese comics, for many younger fans of the medium, are often synonymous with violence, robots, superheroes and cute girls, but the long and memorable history of manga has much more to it than that, and Tatsumi is one of its founding fathers. This epic autobiography (it took him 10 years to draw the 855-page book) spans the postwar period between 1948 and 1960, and portrays Tatsumi’s struggle to survive on the margins of Japanese society while fighting for artistic recognition in a realistic way. In the background we experience the country’s slow return to normality, economic recovery and the student riots of the ‘60s.

8. 1958 Oe Kenzaburo Nip the Bud, Shoot the Kids trans. Paul st. John Mackintosh & Maki sugiyama avalon Travel, 1996

Written when he was only 23 years old, Oe’s first novel tells the story of a group of kids from a young offenders facility who are evacuated from war-torn Tokyo to the countryside. Far from escaping the horrors of WWII, they experience the villagers’ hate and ostracism and are faced with the fact that society – even in these bucolic surroundings – is fundamentally evil, especially towards those who are considered outsiders. A member of the anti-war and anti-nuclear movement since his days as a collage student, Oe displays all his scorn for violence and Imperial Japan’s involvement in a senseless war.

9. Ogawa Ito Restaurant of Regained Love Trans. David James Karashima alma Publishing, 2008

Good food is a huge part of Japanese life, and in this novel, Ogawa Ito describes how food can change peoples’ lives. It turns his heroine’s life around when, after a break-up, she leaves the capital, goes home to her mother and opens a restaurant, thanks to which she is able to spread a little happiness. It truly is a joyful story.

10. 1998 Akasaka Mari Vibrator trans. Michael emmerich Faber and Faber, 2006

When the sense of loneliness is too much to bear, the protagonist of this novel starts to see any chance encounter as a possibility for salvation. It mostly ends up in unfulfilling sex and even more sadness, but Mari Akasaka’s bulimic woman gets lucky when she meets an ex-yakuza in a convenience store and joins him on an incredible and unlikely road trip. The book speaks for and to all those 20 and 30-something Japanese who are continually pressured to conform to rigid social customs and gender roles, and for this reason end up living alone and not able to find a kindred soul to share their lives with.

11. 1997 Kirinonatsuo Out trans. stephen snyder Vintage, 2004

Four women working the graveyard shift at a bento factory become entangled in a murder when the youngest one kills her violent, gambling husband. While very different in character, they all share a deep frustration with the kind of life they are leading, caught between money problems, distant families and a general sense of alienation. Detective fiction writer Kirino Natsuo shows us a grittier, less pretty image of Japan, where low-middle class women struggle to fight the pervasive social, economic and sexual injustices.

12. 1982-90 Otomo Katsuhiro Akira Kodansha, 2009

In the history of Japanese manga “Akira” represents a watershed of epic proportions. When Otomo Katsuhiro began to publish his revolutionary story on the pages of Young Magazine in 1982, nobody had seen anything quite like it: realistic drawings, very detailed backgrounds and Japanese characters who for once looked Japanese (black hair, smaller eyes). All this in a SF story that mixes together echoes of nuclear war and strange religious cults, high technology and street gangs. When the saga reached its end 2,000 pages later, the equally revolutionary anime version had already been released on unsuspecting cinema goers, but the original manga is the real thing.

13. Early 11th century Murasaki Shikibu The Tale of Genji trans. royall Tyler Penguin Classics, 2003

The unlikely author of the world’s first novel was a Japanese lady-inwaiting at the Imperial court who, being a woman, wasn’t supposed to be so erudite and skilled at writing. Lady Shikibu masterfully tells the story of Prince Genji and his amorous exploits, and in the process gives us a stylish and poetic psychological portrait of court life in the Heian Period, with all its customs, intricate rules and scheming aristocrats.

14. 1976 Murakami Iryu Almost Transparent Blue trans. nancy andrew Kodansha International, 2003

After a bitter war, two atomic bombs and a seven-year occupation, Japan’s relationship with the United States became very complex and in some respects is still unresolved. In this plotless collective portrait of Ryu and his friends (This was the author’s debut novel), he goes beyond introspection in order to portray the nihilistic life of a group of people living close to an American military base in Kanagawa. It is 1970 and the student movement has failed in its attack on society, academic education and the war in Vietnam, leading the young protagonists to take refuge in drug-fuelled stupor and senseless sex. But the highs offered by sex and drugs can do little against the general sense of boredom and alienation. It all feels like a long bad trip.

15. 1999 Nakagami Kenji The Cape and Other Stories from the Japanese Ghetto trans. eve Zimmerman stone bridge Press, 2008

Racial discrimination can be found everywhere in the world and is directed against different groups of people, but Japan is unique in that many victims belong to the same race as the perpetrators. The burakumin are a caste whose ancestors did what Buddhism considered “dirty” jobs (butchers, leather workers, grave diggers, etc.) and didn’t have a literary voice of their own until Nakagami Kenji came along and gave them a sense of pride for a short period before his untimely death from cancer. His uncompromising stories show how the burden of social inequality ends up poisoning people’s lives.

16. 2000 Hanawa Kazuichi Doing Time trans. elizabeth Tiernan & shizuka shimoyama Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2004

Hanawa Kazuichi is one of Japan’s best manga artists. He also used to be a model gun enthusiast, but was arrested for tinkering with a piece from his collection and turning it into a real weapon. This biographic book chronicles the two years he spent in jail between 1995 and 1997, and remains an extremely fascinating portrait of prison life. What makes it particularly interesting are all the little details about Japanese prisons – a world apart that in many respects mirrors Japanese society and is light-years away from Western jails. This book is the best explanation of why you should avoid going to prison in Japan at all costs.

17. 1002 Sei Shonagon The Pillow Book trans. M. McKinney Penguin Classics, 2006

The most surprising thing about this collection of zuihitsu (literary jottings) is how fresh and modern they sound now, even though the author wrote about a world far removed from today, both in time and character. Sei Shonagon may be writing about everyday court life in the Heian Period (794- 1185), but her 185 eclectic musings and lists of things she likes and hates show us how little human nature has changed. This is a delightful example of how irony and wit can become a weapon in the right literary hands.

18. 1963 Nosaka Akiyuki The Pornographers trans. Michael Gallagher Tuttle classics, 2006

A former juvenile delinquent who spent time in a borstal, Nosaka Akiyuki knew a thing or two about war, family tragedy and growing up in Japan’s bombed out cities. In this novel that put him on the literary map, the protagonist only aspires to relieve people’s sorrow while hoping to make some money in the process, and what better way to do it than by making pornography! The tragicomic adventures of this band of pornographers offer a privileged look into the country’s kinky past while accurately portraying Japanese male sexuality.

19. 1997 Mirakami Haruki Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche trans. Alfred Birnbaum & Philip Gabriel Vintage, 2003

Murakami Haruki is mainly known for his postmodern, dream-like fantasy novels, but in 1996, after living nine years abroad, he embraced a more socially committed approach to literature by interviewing both the victims of Aum Shinrikyo’s sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, and members of the doomsday cult itself. The book highlights many interesting aspects of the Japanese mentality and the media’s sensationalist approach to reporting. In the end, Murakami concludes that the incident remains a missed chance to analyze the true causes of the tragedy, as most people preferred to treat the cult as an aberration instead of an expression of a general social malaise.

20. 1947 Dazai Osamu The Setting Sun trans. Donald Keene new Directions, 1968

During his short and tormented life, Marxist-influenced Dazai Osamu always felt a sense of guilt for being born into a privileged family. This novel in particular describes the decline of Japan’s aristocracy after WWII by recounting the tale of Kazuko and her once rich family while they try to regain some sort of peace and serenity amid the postwar chaos. The book’s success would help turn the phrase “people of the setting sun” into a popular expression, as the title itself refers to the fact that the once Rising Sun (i.e. Japan) had lost both its material and spiritual wealth.

21. 2003 Kanehara Hitomi Snakes and Earrings trans. David Karashima Vintage, 2005

In the 1990s and 2000s, so-called “gyaru” were all over the place, with their sassy attitude and glamorous clothes and makeup. From their base in Shibuya they would spread the word to a new generation of high school girls, eager to challenge mainstream society. In 2003, at the peak of gyaru culture, 20- year-old Kanehara Hitomi chose one of these teenagers as the protagonist of her debut novel, providing readers with an in-depth portrait of what goes on in the minds of young women today. But Kanehara’s world becomes much darker as her heroine gets her tongue pierced and a large tattoo before plunging into post-bubble angst.

22. 2007 David Peace Tokyo Year Zero Faber & Faber, 2007

One year after Japan’s defeat in WWII, the police are hunting for a serial killer. However, this detective story is just an excuse to show the city of Tokyo reduced to rubble, where the survivors wander around in search of meaning amid the chaos and destruction, much like in Rossellini’s “Germany Year Zero”. In this – the first part of a trilogy about postwar Japan – David Peace marries form and content by adopting a language that is pulled apart, disjointed and repetitive, creating a lyrical and spellbinding story as close to poetry as it is to a traditional novel.

23. 1901 Yosano Akiko Tangled Hair trans. s. Goldstein Cheng & Tsui, 2002

Feminist, pacifist and social reformer Yosano is one of the most famous and controversial woman poets in Japan, and this is arguably her masterpiece. Though most of the 400 verses in this collection are love poems, she exploits the traditional tanka form to assert a new idea of femininity. Far from the accepted social norm, the women depicted in this book are strong, assertive and sexually free.

24. Umezu Kazuo The Drifting Classroom Trans. Yuji oniki VIZ Media LLC, 2006

The way the author of this manga depicts his country in 1972 is fascinating. After the failure of the left-wing movements to impose a new model, the direction Japan took led to its products being distributed world wide. However, dissatisfied with this state of affairs, Umezu conjured up a terrible story. A school is transported into the future where everything is destroyed and where students die of hunger as the author demonstrates his lack of faith in the future Japan has built for itself.

25. 1929 Kobayashi Takiji The Crab Cannery Boat Trans. Zeljko Cipris university of hawaii Press, 2013

This novel was first published in 1929 and immortalized Kobayashi Takiji as the writer of the working class. He was born in 1902 to a poor family in North Japan, and his plans to become a banker changed when he found out about the miserable lives of menial workers. He tackles the subject head-on in The Factory Ship, taking the reader down into the boats used to catch and can crab – a luxury product – into inhuman conditions that stir up resentment and rebellion. This masterpiece of proletarian literature eventually led to the author’s death, but it would achieve great success for a second time in the 2000s at a time of increasing poverty in Japanese society. Today many young people now refer to it in search of an answer to the crisis.

26. 1685 Ihara Saikaku Five Women Who Loved Love trans. W.T. De Bary Tuttle, 1997

Ihara Saikaku (1641-1693) is one of the best Japanese writers of the pre-modern era. During the authoritarian and morally conservative Edo Era, he pioneered a new kind of realistic prose through which he described the “floating world” of the rising middle-class and its liberal attitude toward social interaction. Alas, his characters, and his amorous women in particular, are inevitably confronted with the strict morality of the time and must choose between conforming or breaking the law, with the risk of being sentenced to death. Even so, many choose shortlived happiness over a dull life.

27. 1985 Alan Booth The Roads to Sata Kodansha America, 1997

One of the most famous travel books about Japan tells the story of the author’s journey on foot across the country. Starting from its northernmost point, he covered 3,218km until he reached the country’s southern tip. What really makes this book a wonderful read, though, is Booth’s ability to observe and describe the places he sees and people he meets while walking across Japan’s “wrong side” – the less developed west coast. The book is also interesting in that the author’s ambivalent reactions to these encounters are typical of many foreign residents’ love/hate relationship with the country.

28. 2005, HigashinoKeigo The Devotion of Suspect X Trans. a. o. Smith Minotaur books, 2011

If Edogawa Ranpo was the pioneer of police literature in Japan and Matsumoto his worthy successor, then Higashino Keigo, born in 1958 when Matsumoto’s bestseller Tokyo Express was published, is keeping the tradition going brilliantly. His stories take place in today’s society and his subtle analysis poses questions about his contemporaries. In this novel Higashino questions what will encourage a man to sacrifice himself for love. It also features one of his recurrent characters, the physician Yukawa, who is always prompt in helping the police to resolve difficult cases. This was also one of Higashino’s many works that has been adapted for cinema and TV.

29. 1934-1937 Kawabata Yasunari Snow Country trans. e. g. Seidensticker Vintage, 1996

What strikes you when reading Snow Country is the sheer quality of Kawabata’s writing – showing why he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1968. Despite the lack of action, you will not tire of reading it again and again, like the joy at the first snowfall every year. The author was a regular visitor to Echigo Yuzawa thermal station, where he wrote this novel, and his knowledge of the area allowed him to write beautiful passages describing the landscape, the craftwork and the villages that are always covered with snow. This book is a beautiful way of discovering the “other side of Japan”.

30. 1973-85 Nakazawa Keiji Barefoot Gen trans. Project gen Last gasp, 2005

One of the most stunning and moving tales of wartime tragedy, and also a comic art masterpiece, Nakazawa Keiji’s memoir starts in the days leading up to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and follows the life of the eponymous boy and his surviving family after the war. With a simple but expressive and sometimes violent style, Nakazawa’s pacifist story goes beyond the usual anti-war message to tackle such themes as discrimination against Koreans and the survivors of the nuclear bombings, the Emperor’s responsibility for the tragedy, the relationship between history and memory, and the battle between good and evil.

31. Florent Chavouet Tokyo on Foot: Travels in the City’s Most Colorful Neighborhoods Tuttle publishing, 2009

Chavouet’s first book is a beautiful lesson all about Japan. What characterizes it is his fresh approach and the innocence he brings with regard to the country and its society. Unlike many foreign commentators, he didn’t choose the easy path of picking out Japanese clichés and stereotypes, and has just chosen to record everyday life, as if a taking a stroll through different districts in the capital. The result is astounding. As well as his sense of humour and the quality of his prose, the author has succeeded in painting a very simple and truthful portrait that is the equal of any other quality look at Japan.

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat