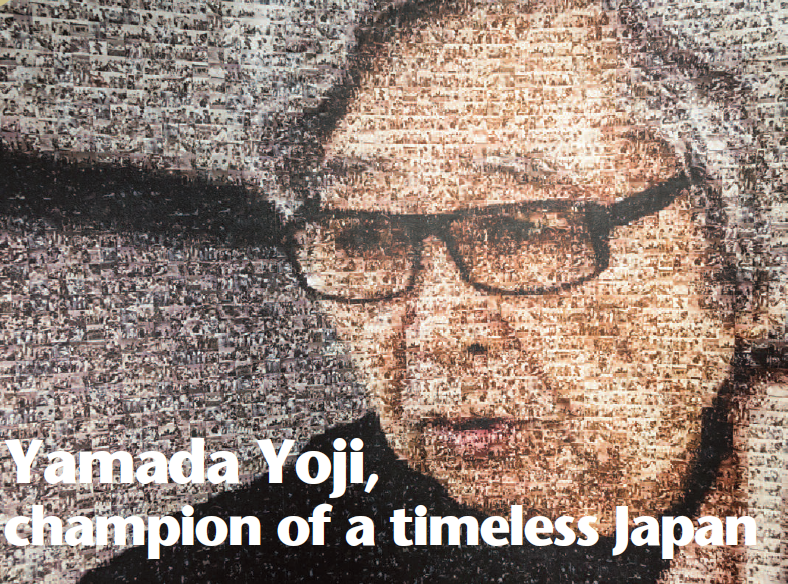

In an exclusive interview with Zoom, Yamada Yoji looks back at his 60-yearlong career.

Let’s start from the beginning. In 1954, after majoring in Law at Tokyo University, you started to work at Shochiku, one of the major film studios in the country. Why did you want to be a director?

Yamada Yoji : To tell you the truth, I had never thought about becoming a director. I liked movies, of course, but I didn’t think I was cut out for directing. At the same time, even though I had studied law, I neither wanted to become a public official nor liked office work. So I tried to become a journalist, but they were not interested in someone with such low grades. At that time the Japanese economy had still not recovered and finding a job wasn’t easy. Eventually I passed a test with Shochiku, so you could say I entered the world of movies almost by chance.

Still, as you said, you liked movies, didn’t you?

Y. Y. : Of course I liked them, but that doesn’t really mean anything. I went to the cinema like everybody else as it was the main kind of entertainment at the time, it was a national pastime. Films were also a window on different cultures and customs, and for many young people like me, watching movies could be likened to a learning experience.

When you began to work at Shochiku, Ozu Yasujiro was still making movies, but at the same time you were just one of many newcomers who was learning the trade. A group of youngsters in particular (Oshima Nagisa, Shinoda Masahiro, Yoshida Yoshishige, etc.) would start the so-called “Shochiku Nouvelle Vague” that changed Japanese cinema in the 1960s. Was it hard for you to find your way between the old masters and these young turks?

Y. Y. : It really was difficult because, as I said, I didn’t know the first thing about making movies. I had to start from scratch and learn little by little, every day, while working as an assistant director.

Speaking of that, both you and Oshima started as assistant directors for Nomura Yoshitaro. How was your relationship with Oshima? Did you compete with each other?

Y. Y. : Yes, of course, but I was no match for him. For one thing, he was more outgoing than me. And from the start he had very clear ideas about what he wanted to achieve and the kind of movies he wanted to make. In comparison I was a real amateur. I always thought if that’s what it takes to be a director, I’ll never be one. That’s why at first I focused on becoming a scriptwriter. I guess the only thing we had in common was our dislike for Ozu’s movies (laughs).

So how did you get to make your first movie “Nikai no tanin” (The Strangers Upstairs, 1961)?

Y. Y. : It was thanks to Nomura Sensei. He found a good story idea for me and went so far as to write the actual screenplay. The original subject was a short suspense novel by Takigawa Kyo, but he suggested I make it into a comedy. The film turned out to be a box office success and my career took off from there. However, I’ve never tried to consciously develop a particular style. It’s been a natural process.

I’d like to ask you about your working method. How do you approach film-making and directing actors in particular?

Y. Y. : As you know some directors encourage actors to improvise their dialogue, but for me everything starts with the screenplay. We rehearse many times until everybody is comfortable with their lines before actually shooting the scenes. This said, the script is also a work in progress, and parts of it can be reworked or changed during filming. I’m always open to suggestions, but the original screenplay is our starting point. Then of course some actors do indeed end up improvising some of their lines, but that’s something only an experienced performer can do.

I heard that you always stay in the same ryokan (Japanese-style inn) whenever you write a new film.

Y. Y. : Yes, it’s true. Creating the ideal working environment where you feel at ease is very important for me, and I happen to like this place in Kagurazaka, in central Tokyo, with tatami mat floors and a low table. It’s a very old house that leans to one side… I guess when I stop making movies they will shut the place down.

So it’s just you and the scriptwriter working at your story until it’s finished?

Y. Y. : Yes, that’s the way we work. I never stay for too long, though. I may spend one or two years thinking about the project while the story slowly unfolds in my head, as there are always two or three stories competing for attention. I consider each of them carefully until I decide to focus on either this one or that one. Sometimes I start to write the script, but I suddenly realize that it’s not coming out the way I want, so I put that story aside and start with a different one. However, when things go according to plan, I usually work pretty quickly. Let’s say it takes one or two months to get it done, sometimes even less than a month.

So it’s also a matter of timing.

Y. Y. : Yes, timing is very important. It’s like keeping wine in a cellar. You must wait for the right time to open the bottles, neither too early nor too late. Sometimes, when you wait too long you realize that a story wasn’t as interesting as you initially thought. But if a story is really good, it will stand the test of time.

Speaking of script-writing, you had a long lasting collaboration with Asama Yoshitaka, didn’t you?

Y. Y. : Yes, we worked together until “Kakushi ken” (The Hidden Blade, 2004), after which he became ill and was replaced by Hiramatsu Emiko.

What was it like working with Asama?

Y. Y. : Obviously, we worked very well together and complemented each other. You see, when you have this kind of partnership it’s important to share the same viewpoint. If you are constantly clashing over different ideas you’re going to accomplish nothing. You must have the same approach about doing things, and must be willing to share the workload and responsibilities. It’s like a horse-drawn carriage – each horse has to work in harmony with the others, pulling with equal strength. Of course, when you make a movie someone has to make the final decision, and that’s the director, but it’s also true that team work and collaboration are very important. Francois Truffaut showed this side of filmmaking very well in “La Nuit Américaine” (Day for Night, 1973). No matter how much money you put into a project or how good a screenplay is, if the team doesn’t work harmoniously you’ll never manage to express your ideas the way you want. But when everything works, and everybody has fun and is committed to the story, you can feel it. There’s something in the air you can almost smell.

Especially while making the 48 films that comprise the “Otoko wa tsurai yo” series, you worked with the same group of people for 25 years. It became a sort of family. How was working with Atsumi Kiyoshi?

Y. Y. : In 2012, when I was awarded the Order of Culture, I had a chance to talk to the imperial couple. Empress Michiko asked me how Torasan was born. I said that without Atsumi there would be no Tora-san. It was after first meeting him that I tried to find a way to use his wonderful talent, and eventually came up with Tora-san. Atsumi was always ready to follow me in my projects. He never said no. I now regret that I asked him to star in the last two instalments, number 47 and 48, even though the doctors were against it. At the same time, he was someone who made a clear distinction between work and privacy. He didn’t like to mix the two. Even I didn’t have his telephone number – he only told me at his farewell party. I think he was sometimes bothered by people blurring the distinction between him and his character. He once told me about being greeted by a drunk at Tokyo Station. He said, “Hey Tora-san, how are you! By the way, how’s Mr Atsumi doing?

Another famous actor who has just left us is Takakura Ken who famously starred in “Shiawase no kiiroi hankachi” (The Yellow Handkerchief, 1977).

Y. Y. : Like Atsumi, he died without fanfare. It was as if he didn’t want to bother other people with his problems. I remember when I first met him at the ryokan in Akasaka where I was working. Ken-san was wearing a denim jacket and jeans. I explained the story to him and he said, “Just let me know when you want me.” Just before leaving he said, “This is a very happy day for me.” That’s something I’ll never forget. Actually, he was the same age as me, so I always thought as long as he’s healthy and keeps working in movies, I can do the same. That’s why since his death I’ve felt a little depressed.

Can you say a few words about Baisho Chieko who has made more than 40 films with you?

Y. Y. : The great thing about Baisho-san is that she makes everybody better. I mean every actor who is lucky enough to work with her looks better. There are many good actors out there who only think about themselves and their work, but Baisho-san is so unselfish in her approach to acting that she has this way of improving every co-actor’s performance. That’s a wonderful and very rare gift.

Like other directors, you always seem to go back to certain themes in your films. One of them is the concept of furusato (home town). What is furusato for you and why is it so important?

Y. Y. : You see, I was born near Osaka but my family moved to Manchuria when I was still a small child. Then, after the war, I spent my teenage years with my aunt in Yamaguchi Prefecture. Both during my time in China and when I came back to Japan, I always moved from one place to another so there’s no place I can really call my home town. When I was a child, I envied my friends when they spent their summer holidays at their grandparents’ place. Even now I feel a bit jealous of those people who have a place to go back to. Even Tora-san, while he is constantly travelling around Japan, sooner or later goes back to his

home in Shibamata. He knows there are people who are waiting for him.

So in coming up with Tora-san’s character you drew from your personal experience?

Y. Y. : Yes, I guess so. I’ve always been drawn to wanderers and people who live on the fringe of society; people who don’t want to conform exactly to social rules. I have no interest and little patience with powerful or arrogant types who like to order other people around. That’s why you’ll never see such people in my films – my characters are people I’d actually like to be friends with. It’s true that having a friend like Tora-san would cause me a lot of trouble, but he is a good fellow after all. He is a little like a no-good little brother.

You certainly grew up in very difficult times, didn’t you?

Y. Y. : You could say that. Both during and after the war, there was a shortage of food and I was always hungry. In that situation nobody talked about gourmet food, you didn’t really care about that and you didn’t have any preferences. Anything was okay as long as you could fill your stomach. That’s something I feel to this day.

But don’t you have any favourite dish?

Y. Y. : Well, something I’m always happy to eat is fried food, like ten-don. Nowadays it’s not easy to find a place that makes really good ten-don. I especially hate the expensive places. Ten-don is supposed to be a simple food, not gourmet stuff. There used to be a good place near here, in Tsukiji, but it’s long gone.

You have mentioned travelling and going home. These themes are often present in your stories. I’ve also noticed that, with the obvious exception of the samurai trilogy, in each of your films there is a train scene. You seem to like trains very much.

Y. Y. : Yes, especially steam locomotives. I’d find it difficult to say why I like them. Maybe it’s because you can actually see all those pistons and gears in action, endlessly moving. I have no interest in the Shinkansen. You can see nothing, and even that noise… piiiiiiiiii… it’s just dumb. You can’t compare that with the choochoo of a steam engine.

You started in movies making comedies and most of your films have a rather light touch, but with your latest work you have tackled weightier subjects. Were you influenced by the current political situation?

Y. Y. : Yes, Japan has taken a dangerous path. People are worried about what is going to happen to the country. They feel anxious – and so do I.

“Kabei” (Our Mother, 2008), for instance, is a family drama set in 1940-41 and opens with the protagonist’s husband being arrested for being a dissident.

Y. Y. : That’s right, under the Peace Preservation Law which targeted communists, labour activists and other opponents of the military regime. Now the situation is not so openly bad and we apparently live in a democratic country, but still there are politicians who would like to wind back the clock. That’s because Japan has never moved on from it’s past. After the war, Germany apologized fully and many people were tried for their crimes. However, in Japan many war criminals just kept their jobs. Even Kishi Nobusuke, who was prime minister between 1957 and 1960, had a murky past to say the least. He is, by the way, current Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s grandfather.

The very interesting Yamada Yoji Museum in Shibamata is divided into several sections. Two of them, in particular, have caught my interest. The first one is titled “Stop and look over your shoulder. Things the Japanese should value about the past”, and the other one is called “Education: learning and teaching”.

Y. Y. : As you can imagine, these two themes are very much connected to each other. I think people in this country really should look back and remember our national past. The younger generation and all those people who were born after the war are at risk of forgetting our history. We must avoid this. We must remember the path this country took in the first half of the twentieth century, and our responsibilities in waging war in Asia and the Pacific. I was born in 1931, the very year the Sino-Japanese War (1931-45) began. I was born on September 19th. One day before, on the 18th, the Japanese army staged the so-called Mukden/Manchurian Incident as a pretext to invade Manchuria. Many lies have been told about contemporary Japanese history. This is something we have to rectify; we must acknowledge our war of aggression. I grew up in Manchuria and saw with my own eyes all the hideous things the Japanese did and the discrimination the Chinese were subjected to. We should be ashamed of what our military has done in Asia. Even when we talk about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where 300,000 people died, we have to remember what led to that tragedy and all the lies people were told by the government. In any case, war is a terrible, horrible thing, no matter what reason you have to start one. Japan is blessed with a pacifist constitution which has made waging war illegal, and we must defend this wonderful document.

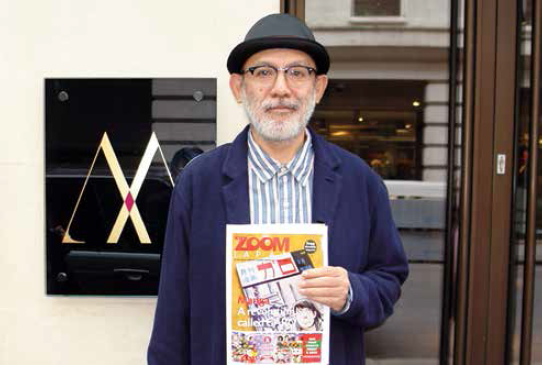

Interview by Jean Derome

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat