With The Little House, Yamada Yoji has at last received international recognition.

Several veterans of Japan’s old studio system, which began to fade away in the early 1960s with the advent of television, are still working. The 83-year-old Yamada Yoji, however, is the only one still directing for the studio he started out with back in 1954. He has directed 81 films for Shochiku, which started making films in 1920 and was once the professional home of Ozu Yasujiro and Oshima Nagisa. Yamada’s biggest box-office success, as well as making of his reputation, was the “Tora-san” series. These 48 films from 1969 to 1995, about the romantic misadventures of the eponymous wandering peddler, not only kept Yamada employed but Shochiku afloat. He has also won his share of kudos abroad, especially for his “samurai trilogy” of straightforwardly humanistic period dramas inflected with action: “Tasogare seibei” (The Twilight Samurai, 2002), “Kakushi ken” (The Hidden Blade, 2004) and “Bushi no ichibun” (Love and Honour, 2006).

The first, “The Twilight Samurai,” was also Yamada’s first-ever film in the costume drama genre. With a story about a low-ranking, family-man samurai (Sanada Hiroyuki) forced to take up his sword for his clan, the film received a Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, as well as winning 13 Japan Academy Prizes, including a best director award for Yamada. Despite his long list of awards, Yamada is still rather underrated by many foreign critics and scholars, particularly when compared to a distinguished Shochiku studio senior like Ozu. For one thing, the “Tora-san” series gave him the image of a populist entertainer, not a serious auteur, though in Japan his standing is higher, with his 1977 road movie “The Yellow Handkerchief” named as one of the 100 best Japanese films of the twentieth century by Kinema Junpo, Japan’s oldest film magazine.

Yamada’s “The Little House” won’t rectify this situation, though it is the kind of Showa Era (1926-89) family drama that has become a Yamada specialty. Born in 1931, Yamada not only lived through the film’s 1935-45 era but also has a fine-tuned feeling for everything from period decor to social mores. The red-roofed house of the title seems to belong in the architectural museum in Tokyo’s Koganei Park, which displays outstanding examples of nineteenth and early twentieth century Tokyo houses and commercial buildings, now rarely found due to wartime destruction and postwar rebuilding. The film similarly preserves the kind of upper-middle-class existence which, to the working classes of the early Showa, was little more than a dream, and today looks cozy and idyllic – and can no longer be found. The chatty-sounding dialogue, co-written by Yamada and Hiramatsu Emiko, is yet another throwback, this time to Ozu, whose 1953 masterpiece “Tokyo Story” was remade by Yamada in 2013 as the rather patchy “Tokyo Family”. The story, like those of Ozu’s films in similar bourgeois settings, is no nostalgic look back at simpler times, though. Instead, it is a tale of illicit adult love witnessed by a pure-hearted young housemaid – and recalled by her decades after the event.

This flashback structure has become common in recent Japanese films set in the tumultuous early decades of the Showa period, which are rapidly passing from living memory and must be explained to younger viewers, or so the filmmakers assume. Yamada, however, also uses this structure to tellingly illustrate how time’s passage softens the impact of emotions and deeds that once seemed life-changing – or rather, marriage-threatening. The film begins in the present, shortly following the death of Taki (“Tora-san” series regular Baisho Chieko), an elderly woman who had been writing reminiscences of her youth with the encouragement of her loving, if jokingly critical, great-nephew Takeshi (Tsumabuki Satoshi).

The story soon shifts to 1935 when Taki (Kuroki Haru), now a bashful apple-cheeked teenager, comes from snowy Yamagata Prefecture to work as a maid in Tokyo. After a year with a sharptongued novelist (Hashizume Isao), she leaves for the suburban “little house” of the title, where Masaki Hirai (Kataoka Takataro), a toy-company executive, lives with his wife Tokiko (Matsu Takako) and their 5-year-old son Kyoichi. Taki is taken with the Hirais, especially the outgoing, cultured and – for a woman of the era – blithely independent Tokiko. Then at a family New Year’s celebration, Tokiko meets Itakura (Yoshioka Hidetaka), a young designer working at her husband’s company. Another immigrant from the far north, Itakura is the complete artist and uninterested in the other men’s talk of war and profits. He and Tokiko, who admires his talent for drawing and shares his passion for classical music, soon strike up a platonic friendship. Meanwhile, Taki is in the background approvingly observing the flowering of this relationship – she also likes the gentle-spirited Itakura. But as it deepens into passion, she becomes alarmed. Yamada has not made the conventional type of love-triangle melodrama. Instead, the film centres on Taki and how this affair (if indeed it is an affair) impacts both her relationship with Tokiko and her later life. From an unsophisticated girl who stands in fear and awe of her exquisitely kimonoed employer, Taki becomes a trusted confidante who can, when the situation demands it, speak the uncomfortable truth to her. Relative newcomer Kuroki Haru managed this transition with grace and aplomb, so much so that she was awarded a Best Actress Silver Bear at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival. The daughter of a distinguished kabuki family, Matsu Takako plays Tokiko as a bubbly and egalitarian sort of person who can suddenly turn aristocratically steely if she is thwarted or denied – that is, she is used to getting her own way and doesn’t much care who knows it. The film itself, though, is uneven towards the end with the big reveal about a secret Taki has been keeping for 60 years. Yamada, a populist to his bones, can’t help hyping the action in approved commercial dramatic style. At the same time, he quietly evokes the era’s many tragedies with hopes denied and futures aborted. And the little red-roofed house itself? You’ll have to search hard and long to find anything like it in Tokyo today – but there’s always that museum in Koganei.

Mark Schilling

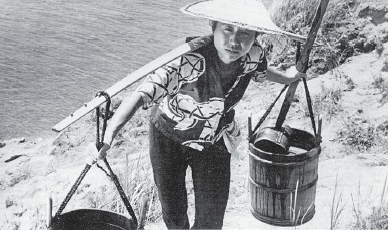

Photo ©2014 «The Little House» Film Partners