Many wounds inflicted by the disaster remain unhealed. They need to be treated before people can move on.

Many wounds inflicted by the disaster remain unhealed. They need to be treated before people can move on.

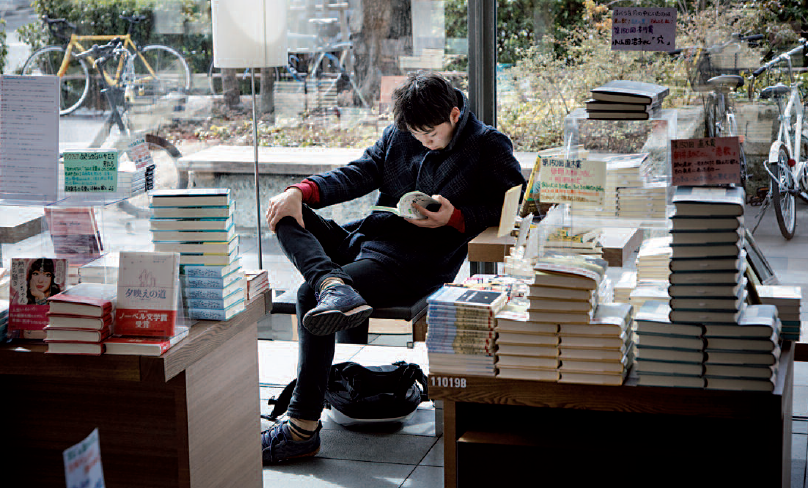

It was raining in the city of Ishinomaki when we got into the taxi, and the driver was muttering: “We’ve had enough of the the rain here”. In his opinion, the ground level in Ishinomaki sank up to 1.2 metres after the earthquake, and even now, everywhere becomes flooded as soon as there is a drop of rain. Even now, four years after the disaster, the city still has to deal with many problems that prevent its residents leading their lives as they used to, including psychological damage. It is also feared that some wounds will remain untreated. “Just after the earthquake, while chaos reigned, the citizens from the Tohoku region were praised for their bravery and patience as they faced the disaster without complaint, but in reality, keeping quiet about their suffering had significant psychological consequences,” explains Akiyama Yuhiro, a reporter from Ishinomaki Hibi Shimbun. We also interviewed Takeuchi Hiroyuki, a retired reporter appointed head of the “kizuna no eki” (Liaison Station), set up for people to come to meet and talk about their issues (See Zoom Japan, n°21, May 2014). “Those who come here can get everything off their chest and share their problems with us. We hear things that are never mentioned to reporters with their pens and notebooks – anxiety about daily life, psychological trauma when family members have been declared missing. People need to be treated differently depending on whether they are grieving for those who have died or who are still missing. These families don’t know how to deal with the uncertainty. They will have to find a way to grieve at some point. These days, I often think about Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder. I have a feeling that the number of people suffering from it is on the rise – it’s very worrying. In my opinion, we can say it’s the same for children who are taught to be brave without ever complaining”. Mrs Ohta Tomoko, who lives in Sendai, set up the organization “Kids Media Station” with the aim of encouraging children to speak out in the future and share their experiences.

In Ishinomaki she also set up “kodomo kasha” (junior reporters), a scheme where children visit places that have been damaged, do research and then write newspaper articles about their first-hand impressions. The costs for both of these initiatives are covered by different organizations that support the reconstruction process, or by private and corporate donations. Another such idea is the Peace Boat Centre, active since the earthquake first struck, that continues to welcome volunteers from outside the prefecture and puts them in touch with places that need help. Since October 2011, this group publishes a bimonthly newspaper, Kasetsu Kizuna Shimbun (Temporary Housing Residents’ Liaison Newspaper), to provide news to those residents living in temporary housing. The newspaper is delivered by hand in order to ease people’s sense of isolation and to help prevent suicide. Expenses are covered by occasional publicity drives by local shopkeepers and a grant from the American disaster relief organization AmeriCares. Yet another group, Mirai Sapooto Ishinomaki (Support for the Future of Ishinomaki) has set up Tsunagukan (The House for Sharing Memories) in the city centre, where the extent of the damage is displayed on panels and meetings are organized to listen to disaster victims speak about their personal experiences. They have also developed applications for smart phones and tablets that can display the damage caused by the disaster and allow people to discover the past, present and future of Ishinomaki while walking around the city on a virtual tour, seeing how any particular place looked just after the disaster struck. However, their future activities are uncertain. “The organization’s activities are funded through subsidies. Once the reconstruction period is over, their funding will be in doubt. Moreover, some people disapprove of the way the earthquake has become an object of tourism. We think that all these activities should only be directed towards saving people’s lives,” comments Nakagawa Masaharu, the organization’s spokesman who came to Tokyo as a volunteer and chose to remain there to help from closer to the seat of power. In the year following the earthquake, a total of 280,000 volunteers came to the city. In spite of the chaotic situation in the beginning, an effective aid system was put in place early on as a result of close collaboration between the administration (including the Self-Defence Forces), the Volunteer Centre that took care of private volunteers, the Associations’ Coordination Committee and Ishinomaki Senshu University, which provided a base for the volunteer efforts. Today, there are still people from the affected areas who are living in fear due to the precariousness of their daily lives. However, as we have observed, there are people all around who are working to ensure the future of this place, with the national government providing funds and different groups negotiating how they are shared out. The best conditions for renewal to take place rely on all parties concerned coming together and pulling in the same direction, while remembering to keep an eye open for what is not immediately visible.

Koga Ritsuko

Photo: Koga Ritsuko