Abducted in November 1977, aged 13, her parents have been fighting for 37 years to bring her back to Japan.

Abducted in November 1977, aged 13, her parents have been fighting for 37 years to bring her back to Japan.

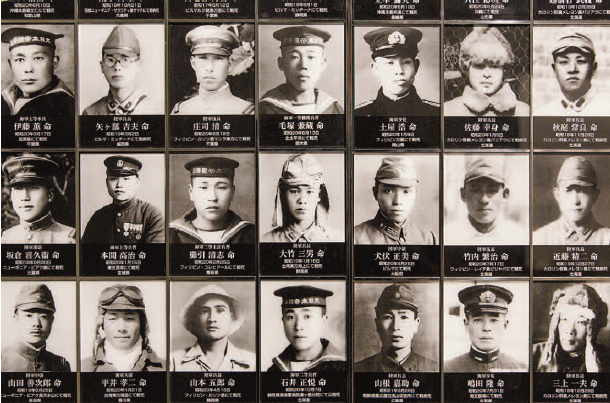

In a small living room next to the main door of a building in the suburbs of Tokyo, we are waiting for the Yokota family. This is where reporters from around the world come to interview the couple who, sadly, have become famous since their 13 year old daughter was kidnapped one day in November 1977. For more than two decades, no-one knew about their tragic story until it was uncovered in 2002, to reactions of horror and bewilderment, when it was discovered that dozens of Japanese citizens had been abducted by North Korea in the 1970s and 1980s. One of them was the Yokota’s daughter Megumi. “You must not believe all you read. They said that Megumi committed suicide in hospital, but we never got her ashes,” Yokota Shigeru explains in a trembling voice. His wife Sakie smiles and offers us some tea. The Yokotas, 81 and 78 years old respectively, are still hopeful that they will one day see their abducted daughter again. We are in Niigata, close to the Sea of Japan, “a harbour where many ships that plied between Niigata and Wonsan used to dock,” Mrs Yokota tells us. Until the night that Megumi disappeared, the family led an ordinary life; the father was a banker and the mother a housewife, who took care of raising Megumi and her two younger twin brothers. “We thought she might have run away, but all the while we knew that wasn’t the case,” Mr Yokota tells us as he opens the family photo album.

A beautiful photo shows all five of them together by the sea. Two years after Megumi’s disappearance, the Yokota family stumbled upon a report in the Sankei Shimbun newspaper. An investigative reporter had made inquiries all along the Japanese coast in pursuit of a story about some “strange events” involving a couple found handcuffed on a beach with their heads covered by a bag, who had narrowly escaped a kidnapper identified as foreign by the over-politeness in the way he spoke Japanese. The reporter crosschecked the incident with other disappearances around the area, and suggested for the first time that North Korea might be behind the Japanese abductions. The Yokota family hurried to the publishers, but they were told their daughters disappearance did not match the pattern. “They said she was too young,” sighs Yokota Sakie. Explaining how there were no further leads for another twenty years, she says that “It was as if Megumi had been ‘kami kakushi’, hidden by the gods”. The Yokotas moved to Tokyo, and to counteract the overwhelming grief, Sakie found refuge in religion. Mr Yokota turns the pages of his album. Megumi appears for the last time in a red kimono against a background of brilliant white snow.

Eventually, in 1997 a reporter back from North Korea came to visit the Yokotas with incredible news: a North Korean spy had revealed information about a 13 year old girl who was captured in the 1970s. Tears ran freely, it was their first lead in twenty years. A former spy named An, who had been trained by Kim Jong-il, agreed to meet them. His confession was devastating. “Back then, all spies had to return with a hostage. I feel guilty myself about Megumi because I could have been the one to kidnap her. The person who did it did not realise he’d abducted a kid,” he explained in an filmed interview. Trained to kill, North Korean spies were under orders to capture a Japanese person in order to learn how to behave like one. “He told us that Megumi had been kidnapped and taken away by boat. During the 40 hour long boat crossing, she vomited and clawed at a door to open it until her nails were torn out,” Mr Yokota tells us in a strangled voice. For her parents, the only thing that matters is that she has been seen alive. However, Pyongyang continues to deny that Megumi was abducted. The Yokotas decided to take action, and in 1997 they organized a group for families who had fallen victim to abductions by North Korea. “An unbearable climate of fear hung in the air. Families who’d lost a member did not dare to speak out. My husband and I were tormented by the idea that if we revealed Megumi’s case to the world we would endanger her life; but it was the only way,” Yokota Sakae assures us. Their determination helped motivate other victim’s families. Together, they collected a thousand signatures for a petition and the government set up a crisis unit with the name ‘Rachi mondai’ (the abduction issue).

However, relations between Tokyo and Pyongyang soon fell victim to political game-playing that left little room for resolving the problem. In March 2000, the victims’ furious families violently demonstrated outside the Liberal-Democrat Party headquarters against sending rice to relieve famine in North Korea. “Take the abduction issue seriously! Give us back our sons and daughters!”, they chanted. It was in September 2002, on the occasion of a historic visit by Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro to Pyongyang, that the case took a new turn. The head of the Japanese government vowed to resolve the issue and took with him a video-cassette for Megumi filmed by the Yokotas, with the simple message “We live in Kawasaki. Your brothers have married and have children. You know, there’s even a Disneyland here now”. The hope that those who were abducted would be freed sent a tremor of emotion through the heart of every anxious family, but Koizumi returned with bad news. North Korea had admitted to the abduction of 13 people, but announced that 8 of them had died in unusual circumstances (gas poisoning, drowning, car accident). Megumi was said to have committed suicide by hanging herself aged 29 while in a psychiatric hospital. The country was in a state of shock and Megumi’s parents were inconsolable. And yet, hope returned when there was no proof of Megumi’s death. “According to experts, the photo brought back by Koizumi does not match the way she should look at 20 years of age as they claimed,” Mr Yokota tells us as he shows us a portrait of Megumi. Their daughter, in school uniform, has become a beautiful young woman with a far away look in her eyes. “We learned at the alleged time of her death that we were also grand-parents of a little girl,” his wife adds. A month later, the surviving hostages were freed and welcomed back with tears of joy. The surreal story of those abducted by North Korea was finally fleshed out. Two of the abducted, Kaoru Haisuke and her friend Okudo Yukiko, kidnapped in 1978 in Niigata, say that Megumi was seen later than 1993. According to a spy, she was teaching Japanese to the son of Kim Jong-un, a highly responsible position that would have been closely supervised, leaving no room for a possible suicide.

Haisuke passed on a message that they are welcome to visit North Korea. “We immediately suspected a trick,” explains Sakie, who has always refused to go. Despite their grand-daughter’s pleas, the Yokotas have kept to their decision. “I dream of holding my grand-daughter in my arms, but if we go over there, they will try everything to make us officially acknowledge Megumi’s death,” she says. In 2005, Megumi’s ‘remains’ provided by Pyongyang were analysed. The DNA did not match, but Megumi still did not come back. Twelve years have gone by. “And there have been twelve prime ministers since Megumi was abducted,” Sakie observes wearily. “We are old and tired. We have begged the government to intervene and organize a meeting in a third country with our grand-daughter, who’s now 26 years old”. Miraculously, this meeting did finally take place in Mongolia in March 2014. “We weren’t able to talk about Megumi. But those few moments of intimacy we spent together, all five of us, with Hegyong’s family, were incredible. I asked her to tell her mother that we knew she was alive, and that we would fight until the end”. According to some sources, around 800 to 1,000 hostages are said to be in North Korea. Out of them all, Megumi’s story has become the symbol of a battle for human rights, but above all for the indestructible love of two parents. “I have nothing against North Korea. I was brought up to respect others. We only ask that our daughter be returned to us,” Sakie exclaims. Her husband nods his head. “It’s been 37 years. This is our last chance”.

Alissa Descotes Toyosaki

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat