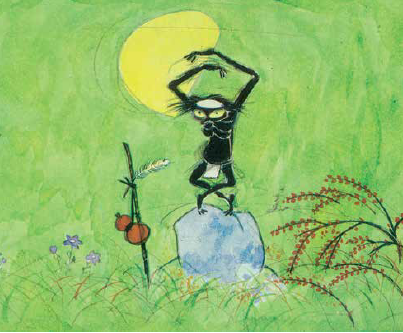

A kappa, as imagined by Katsumata Susumu, an extract from issue 67 of Garo, October 1969. collection Claude Leblanc

Yomota Inuhiko was a long standing contributor to Garo. He recalls the monthly magazine’s influence on society.

The creature known as Garo could be a spectre standing on the side of a river, mocking humans. Some believe him to be similar to a kappa (a mythical “river child” from Japanese folklore) called Kawauro or Kawataro. No matter what he’s called, in Japanese folklore he is considered to be an important presence, as close to the gods as he is to children. Garo also signifies a man compelled to live on the margins of society, banned from the centre of towns and villages. In Osaka the word “Kadaro”, referring to just such an outsider, is a grave insult. Ostracism is still a serious issue today in Japanese society, as illustrated by the case of the Burakumin (a group that have historically been persecuted). Rightwing writers have always written novels depicting generals and famous samurai such as Miyamoto Musashi. Inspired by the high moral standards of these exceptional characters, readers turn them into role models.

However, more left-wing writers, mangaka or film directors will spin stories in which the heroes are not famous celebrities, but ninjas who work as slaves under their command. Ninjas come from humble stock, even humbler than those samurai from the lowest social orders. Exploited by those in power, their mission is to gather information about the enemy, sometimes having to commit sabotage, or even murder. After completing their mission they are either left to their own devices by the powers-that-be, or worse still, are killed off so as to leave no witnesses. Having gone to Berlin to study avant-garde art in the 1920s, Murayama Tomoyoshi, who dedicated himself to proletarian art on his return to Japan, had his ninja stories published in the Communist Party’s newspaper until the day he died. Some of them were made into films and the genre eventually became mainstream. Shirato Sanpei, the founder of Garo magazine, was the son of Okamoto Touki, a friend of Murayama who played a similar role in the proletarian art movement. Moreover, he was a certain Kurosawa Akira’s art teacher.

Shirato has inherited his father’s communist beliefs and objection to militarism. When he started his career as a mangaka in the 1950s, his favourite subject was the ninja. Instead of spinning great stories about assassinations, he focuses on the ninja’s miserable way of life, working like dogs for their masters. In manga of epic scale, ninja take the lead in rural uprisings, but having broken away from the ninja community, they must survive as a traitors. In the mid-60s, the stories imagined by Shirato achieve the status of a “bible” for many students involved in the fight against war and American domination. The most committed of them confessed they would read Shirato’s manga to study the historical materialism of Marx and Lenin. At the end of of the 1960s, amid the barricades at Tokyo University, classes were organized using Shirato’s works as textbooks. Garo was originally the name of a ninja character in one of these manga. Tall and slender, he possessed the power to read people’s thoughts and manipulate them by hypnosis. He hated that the ninja community was at the mercy of those in power and came up with a plan of escape. To survive, he would sometimes use his supernatural talents to fight his fellow ninja, who attempted to kill him for being a traitor. The monthly magazine Garo first came out in 1964, borrowing the name of this most unusual ninja.

Its editor, Nagai Katsuichi, used to work for the secret service under the Imperial Army’s command, and although his point of view was very different, he had great respect for Shirato. For his part, Shirato wanted to make this new magazine his very own. Every month he would publish his signature story Kamui-den. The story follows three young men from three different backgrounds, samurai, farmer and burakumin, as they fight for freedom and liberty in 17th century Japan. Fifty years later, the story is still going strong. The start of the 70s was accompanied by a decline of the new left. In the circumstances, Shirato wondered how he might best continue with Kamui-den, and decided to leave Garo. In his place, a new generation of mangaka started working for the magazine, including Sasaki Maki, Hayashi Seiichi, Katsumata Susumu and Tsurita Kuniko. Their focus was more on exploring the possibility of an experimental avantgarde for manga. Halfway through the decade, the magazine turned a new page in its history. New authors emerged, whose philosophy was to distance themselves from the world around them. Their approach could have been interesting if it hadn’t translated into cynicism about the political commitment of the 1960’s. The attitudes of these new writers reflected the prevailing thought of the Japanese in the 80’s, and when Nagai Katsuichi died in 1996, Garo was split in two, causing difficulties for many of its contributors. When the magazine was discontinued in 2002, what struck us was that the role it had played also disappeared. For 40 years Garo had stood alone in its fight against the world of commercial manga. I wrote for this magazine for ten years and not once did I do it for money.

Yomota Inuhiko