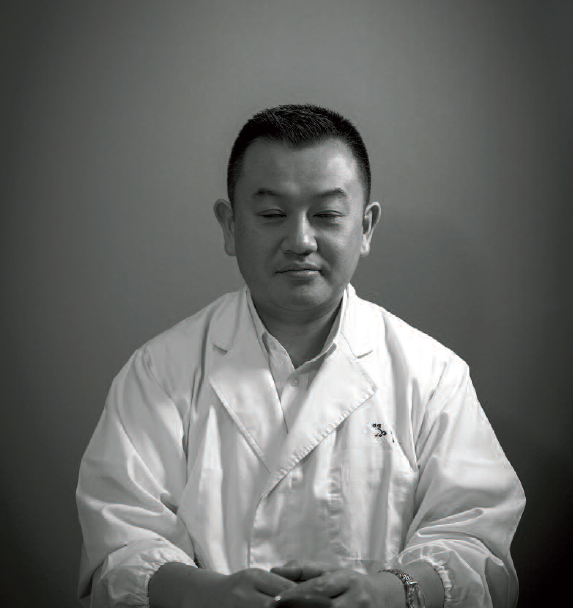

To work in one of these big shops selling the finest goods means acquiring a proper set of skills. This is the tale of how one woman did it.

Born in Tokyo and raised in the United States, Sakamoto Yukari trained as a chef and baker at the French Culinary Institute,

and as a sommelier at The American Sommelier Association. She has worked as a sommelier at the prestigious New York Bar and Grill in the Park Hyatt Tokyo. She also passed the rigorous exam to become a shochu advisor (shochu is a distilled spirit native to Japan) after an apprenticeship at Coco Farm and Winery in Ashikaga, Tochigi prefecture. Sakamoto teaches classes on food and spirits, writes about them in several newspapers and magazines, and even conducts culinary tours of Tokyo’s shops and markets.

Sakamoto shared with Zoom Japan her memories of working at Takashimaya’s flagship store in Nihonbashi as a sommelier in the depachika’s wine department.

What exactly did you do at Takashimaya?

Sakamoto Yukari : I was a sommelier in the wine department. But I was also responsible for other alcohol like sake, shochu (typically distilled from barley, sweet potatoes, buckwheat, or rice), Japanese whisky, beer, you name it.

What was your daily routine? Describe your typical day?

S. Y. : The first two minutes we stand to attention and greet the first customers with a bow while saying “Irasshaimase!” (welcome). This is something all the Japanese take for granted, but it’s funny to see the faces of the foreign customers. They look so surprised! After that I was usually on standby, waiting for customers to ask for advice. Some people already

know what they want and don’t need any help, but others will come and say they are having a party, or will show you what they have bought for dinner and ask what kind of wine I recommend. Every day was different and it also changed according to the season. In Japan, department stores are especially busy in summer and at the end of the year when people give gifts to relatives, teachers and business acquaintances. In summer, during the ochugen season, people commonly choose beer, while in December, during o-seibo, a popular gift is the kohaku set, a boxed set of red and white wine. Sake, of course, is popular all year round. Then you have Valentine’s Day, which many people celebrate with champagne.

Do you think the recession has affected this kind of seasonal shopping?

S. Y. : In the beginning, I mean in the late 1990s and at the turn of the century, the practice of gift-giving was hit rather hard as many people and companies scaled down their spending. However, in recent years depachikas have experienced increasingly stronger sales for higher-priced items, so it’s definitely coming back. Anyway, I worked at Takashimaya, which is a very traditional store – the oldest in Japan – and particularly popular with older customers. For these people seasonal gift-giving is an important social ritual and they would never think of stopping this tradition, no matter how bad the recession is. In this respect Takashimaya, like Mitsukoshi, is different from other department stores such as Matsuya and Isetan, which usually attract a younger clientele.

How about the selection? Do you find the kind of goods you can actually buy in each department store is different?

S. Y. : There’s a big difference, even when you consider different branches of the same department store. For example, the typical customer at Takashimaya’s Shinjuku store is around 30 years old and has very different tastes from the more traditionally minded people who shop in Nihonbashi.

Many people put Isetan’s depachika at the top of their list. Why is that?

S. Y. :Well, about 7 or 8 years ago they did a big renovation and changed the way they displayed the food. In comparison, in other places like Takashimaya’s Yokohama store you can see their presentation is quite old-fashioned and they still use the same old display cases. Of course they are functional but not so beautiful. Isetan, on the other hand, knows how to make the most of their products. You can see it in their clothes and jewellery displays; it’s not only the food. In this sense Isetan has been a trailblazer, and other department stores have followed in its footsteps. Mitsukoshi did it a few years ago, and Ginza Matsuya in Ginza was renovated just this spring.

So we can say that Japanese department stores, and their depachika in particular, are trying to adapt to the times and meet their customers’ changing needs, right?

S. Y. :Yes, that’s definitely true. Internet shopping is more and more popular as it’s often cheaper and more convenient, so the department stores have to find new ways to attract customers.

One thing I believe keeps attracting customers to the depachika is the habit – which I really love – of offering bite-sized samples to taste. Some guidebooks actually suggest tourists who are travelling on a budget should stuff themselves for free in these places and save on lunch.

S. Y. : Yes, I know that. Even in my department we were constantly introducing wines from different regions, and in the sake section every week they would showcase a different kura (brewery). This way the customers can have a taste before they make up their mind. I know that some people – not only the foreigners – treat this system like a free buffet. Ten years ago, even in Takashimaya there were many more free samples on offer. Now they’ve got wise to this and keep them behind the counter. They wait for a customer to really show an interest in their products. Once they’ve struck up a conversation and see the customer is really interested, then they take them out. Anyway, most people in Japan have a different mindset. They think that just getting free food without buying anything is not polite. So they usually grab a sample only if they are really interested in making a purchase.

By the way, do you know how many shops there are in most depachika?

S. Y. : On average I’d say about 150, but Tobu in Ikebukuro has a whopping 250.

What did you particularly like about working in a depachika?

S. Y. : On a selfish level, I could see how the cuisine changed all year round according to the seasons. On a more professional level, it was nice to see a customer come back over and over again and to be able to develop a closer relationship. This is the kind of service that makes people return to the same place again and again. It’s because we show we do care for our clientele, and they in turn develop a strong loyalty for a certain department store.

Interestingly, some foreigners – especially foreign residents in Japan, complain about the service they get in a depachika, or in other food shops for that matter. In other words, they sometimes feel it’s a little over done, like all the unnecessary paper wrapping they get. As someone who was raised in America do you feel the same?

S. Y. : I understand what you mean, but I must say I just love it. I’ve lived in Japan for many years now and every time I go to the US I’m shocked by the lack of courtesy shown by many shop assistants there, like they never greet you or say thank you. In Japan, on the contrary, they go out of their way to make you feel special. All the talk about omotenashi (hospitality) is true. For example, if you buy five boxes of sweets and you plan to give each of them to a different friend, you can actually ask for five extra bags and they are more than happy to oblige. When I started working at Takashimaya, for instance, one of my first jobs was to wrap things up, which is far from simple because the way you do it and the paper you use changes according to the occasion.

Why do people in Japan (and women in particular) love depachika so much?

S. Y. : First of all, a lot of the top brands in Japan have a shop outlet there, so you can find the best food the country can offer, all under one roof. In Takashimaya, for example, you can visit Peck from Milan. Even now, whenever I pay a visit there I never forget to get myself a ciabatta or focaccia with ham or salami from Peck. Or I can get authentic croissants and it makes me feel like I’m in a French bakery. We are so spoilt in Japan. Another thing that makes depachika so popular is that you can get a quick meal, either at an eat-in counter, or you can buy some sushi or a bento box and eat it in the picnic area on the rooftop. Not many foreigners know this, so every time I lead someone on a tour I always point out these roof gardens, which are actually quite nice. They have tables and chairs, and drinking alcohol is allowed too, so you can grab a beer or a small bottle of sake and enjoy it with your tempura or tonkatsu or whatever.

Do you have any more tips for people who want to check out a depachika on their next trip to Japan?

S. Y. : Foreigners are endlessly fascinated by the very expensive fruits they see on display in the department stores or specialty shops. Senbikiya, for example, sells such gift items as 15,000 yen melons, or six peaches for 10,000 yen. But if you buy one of their fruit-topped desserts you can actually have a taste of what’s on offer without breaking the bank. Also, every department store often has some kind of food-related event taking place on the upper floors, such as a fair featuring 15 vendors from Kyushu or Hokkaido. They advertise them on their websites, but if you can’t read Japanese you can always ask at the information office.

Interview by J. D.