The leader of neo-manga is presenting his work in europe for the first time with an exhibition in Toulouse, France.

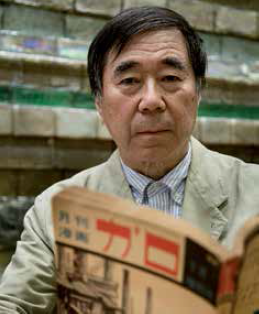

Yokoyama Yuichi’s manga defy convention. There is something alien in the stories that the 47-year-old graphic designer and illustrator creates that never ceases to surprise a reader who unwittingly steps into his world. Then one realizes that the author himself is far from your average person. Yokoyama has cultivated a sphinx-like persona which deflects any intellectual probing into his work. Proud of not owning either a computer or a television, he prefers fishing to reading other people’s comics and finds recording his conversations with friends more interesting than listening to music. More than his quirky character though, comic fans around the world are dazed and confused by his novel brand of manga. Titles like “New Engineering” (2007) and “Travel” (2008) are intensely visual experiences that delight in dragging readers out of their comfort zone while drowning them in a mesmerizing sea of geometric forms, gigantic machines and sprawling urban landscapes.

How did you become a manga artist?

Yokoyama Yuichi : I graduated from Musashino Art University’s oil painting department. After graduation I mainly focused on painting, but I gradually moved to manga. I found working on a single canvas increasingly unsatisfying. On the other hand, the medium of comics gave me a chance to develop a story. I particularly like the fact that through manga I can visualize the flow of time. In the beginning, I also found it difficult to master the use of colour, so I felt attracted to the black-and-white world of comics. Even now that I am more at ease with colour, I think the way I use it is typical of a painter, while my overall approach to image creation (e.g. page layout) is closer to a manga artist.

Four years ago you said that making manga had become your main artistic activity and you treated painting like a pastime or a secondary job. has your opinion changed since then?

Y. Y. :No, not really. I like the fact that a manga is printed in thousands of copies and can be read and enjoyed by many people around the world. That’s important because I want my creations to be seen by as many people as possible. Also, I don’t really care a lot about art preservation. Taking care of a painting and preserving it for the future is not for me really, so I like manga’s ephemeral nature.

Apparently your lack of success was another factor in putting oil painting to one side. Is it true?

Y. Y. : Well you see, when I was in my 20s I took part in 24 art competitions. Not once did I win a prize. That was when I realized I had no future as a painter. When you add the fact that art supplies are expensive, and that all the unsold pictures take up a lot of space… Ironically, my success as a manga artist has created a new interest in my so-called “fine art” work as well. I was very happy when I finally had my first solo exhibition at the Kawasaki City Museum a few years ago. I owe all this to my manga.

You were born in Miyazaki prefecture but have lived all around Japan. Do you think this constant moving has affected your artistic vision?

Y. Y. : Yes, I think so. My father was in the military, so we moved around. This has contributed to developing my interest in the landscape, and the constant sense of awe and mystery that space inspires in me.

Do you think your father’s job influenced you in other ways?

Y. Y. : Like all military men, he paid a lot of attention to good form and manners. He would get angry with me if I wore my shirt untucked or my hat sideways. Now, I don’t know how directly I was influenced by him, but it’s true I like order in nature. It gives me a sense of security.

On the other hand, one of your manga’s more striking features is your characters’ flamboyant appearance. Their faces and clothes are very alien-looking. Why is that?

Y. Y. : First of all, I’ve always been interested in strange, unknown civilizations. Also, I like to create stories and characters that are not too obvious as far as time and place are concerned. My stories may be happening in the future or in a faraway galaxy. I like this vagueness. Last but not least, I’m into fashion, and my approach to storymaking gives me the opportunity to experiment with exotic clothes-design.

All your characters appear to be men. Is that true?

Y. Y. : Yes, it’s true. The simplest reason for this is that, alas, I can’t draw women well. But it’s also true that according to Buddhism, women are impure beings who are known for disrupting the peaceful flow of time. That’s why, for instance, they are kept out of sumo.

Where do you get your ideas for stories?

Y. Y. : I get inspiration from many things. It could be something I read or saw on TV, or a seemingly banal occurrence. It could be anything, really.

I heard you are not very interested in other people’s comics.

Y. Y. : Yes, I’m always asked about my artistic influences or preferences, but I have none, really. The only mangaka I really like is Shiriagari Kotobuki. I like his style.

Judging from your manga, you seem to be more interested in cinema than comics. Do you have any favorite movies or directors?

Y. Y. : I particularly like Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Solaris” and “Stalker” and Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey”. However, my stories are not meant to be seen as science fiction. They certainly have some futuristic elements, but my aim is to create timeless stories, whose meaning goes beyond any particular period. One thing I don’t like about SF is that those stories usually see the future as a development of the present. What I’m trying to create, on the other hand, is a sort of speculative fiction. In other words, what would we look like if our civilization had developed in a different way? What values would we share? What kind of aesthetics would we develop? Maybe nobody would wear shoes but everybody would hide his face behind a mask. Maybe we wouldn’t communicate through words. So you could say that” all my stories are predictions. That’s why, I believe, many of my readers find the worlds I create so unfamiliar. It’s because I don’t give them any easy points of reference.

There’s a poetic quality to your comics, but it comes entirely from the drawings. in Garden (2011) you have introduced more dialogue, but even there the words are very limited. Are you not interested in expressing yourself through words?

Y. Y. : I don’t want to depend on the quality of words and dialogue, because we can never have a perfect translation into foreign languages. Words and dialogue are not universal. Also, I like my stories to be open to interpretation. People ask me about symbols and hidden meanings, but the truth is, there are no intellectual explanations to what happens in my stories and why people behave in a certain way. My readers can see whatever they want in my comics, and you will agree that a lack of words and explanations make a story more ambiguous.

Why do you think your stories appeal so much to foreign readers?

Y. Y. : To be honest, I find foreigners often have a better grasp of what I’m trying to do than the Japanese. In Japan I always get comments like “your drawings are so detailed” or “your stories make me laugh”, but that’s not really the kind of reaction I hope to get from my readers.

Speaking of detailed drawings, on average how long does it take you to complete one story?

Y. Y. : “Travel” and “Garden” took me about a year each. “Sekai Chizu no Ma”, though, was a much longer affair. I spent a couple of months developing the plot and making the first draft, but then it took me about a year and a half to finish the project. I really spent too much time on that project.

Time, and the depiction of time, seem to be a central feature in your manga. Many firsttime readers are often baffled by the way your stories end abruptly without a reason.

Y. Y. :That’s because people are used to standard stories with a beginning and an end. They need a punch line. But those are just conventions and have nothing to do with real life and the way time naturally unfolds. That’s why my stories begin in the middle. It’s like when you turn the TV on and catch a movie in the middle. You only watch 10 or 15 minutes of it. Why are the characters behaving like that? What’s going to happen after you turn the TV off? We don’t know. It’s left to your imagination.

Interview by Jean Derome

Photo: Yokoyama Yuichi