Since he created Domo, NHK’s star character, this animator has experienced great success.

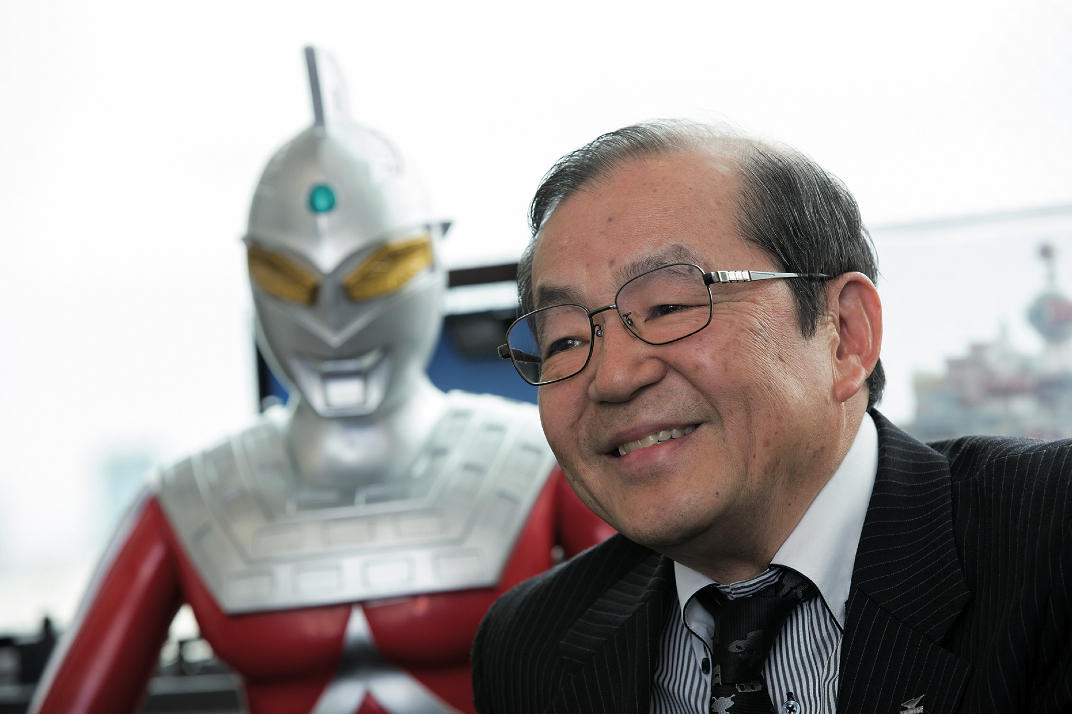

A Japanese dwarf is conquering the West, one country after another, with its army of cute monsters and animals. The dwarf in question is Goda Tsuneo’s animation studio. Since the late 1990s, Goda has created a number of popular characters whose fame has crossed continents, reaching Europe and America. Zoom Japon/Japan visited the dwarf studio in Tokyo’s western suburbs and met Goda himself, chief animator Minegishi Hirokazu and producer Matsumoto Noriko.

Goda-san, you are especially famous for creating Domo-kun, a beady-eyed, furry creature that keeps its jaws constantly open but turns out to be just a clumsy and kind-hearted monster. How was Domo born?

Goda Tsuneo : In 1998, when I was working in the creative department of TYO Productions Inc., NHK was looking for a commemorative character to celebrate the 10th anniversary of its satellite channels. Until then, I’d never really thought about TV characters, and it was only after a meeting that we decided we had to submit something. I remember I stayed up all night trying to come up with an idea. I was just drawing simple shapes at random – circles, triangles. Then I drew a rectangle and suddenly Domo-kun materialized in front of my eyes. I was there, at three in the morning, staring at that thing, and little by little I came up with a story. The first vision I had was this monster in a dark cave that stares blankly at a TV set.

But NHK was actually asking for a set of three characters, right?

G. T. :Yes, because NHK has three satellite channels, BS1, BS2 and High Vision. Now I had this strange creature (laughs) and a bunny I had drawn about the same time, so I needed a third character. The story was set in a cave, so it was only natural to add a bat. So as you can see, stories are sometimes born out of random scribbling. Why NHK chose Domo-kun, I really don’t know (laughs).

Although, the bat doesn’t appear very often, does it?

G. T. : Yes, even though he still shares the cave with Domo-kun and Usajii the bunny.

How did you come up with Domo-kun’s name?

G. T. : Well, I was racking my brain, trying to think of something good, and then I heard the guy next to me talking on the phone. He was like “Domo, domo… domo, domo… domo, domo!” which would be something like “Yes, yes, yes… okay, okay… thank you, bye!” And I thought, okay, Domo! (laughs). Domo in Japanese can mean many things, like ‘thank you’, ‘I’m sorry’, or even ‘goodbye’, so it’s a very useful word.

Since creating Domo-kun you seem to have wholeheartedly embraced the world of animation.

G. T. :That’s right. I began to use these characters more and more often until I left my commercial production company, began to write children’s books and supervise production of character goods, and finally in 2003 I launched dwarf.

And in the beginning were you alone?

G. T. : Yes, that’s right. I rented a studio but I soon realized I couldn’t do everything alone, so I began to call some of the people with whom I had been collaborating since 1998 for Domokun’s stories, like chief animator Minegishi Hirokazu and producer Matsumoto Noriko. They officially joined dwarf in 2006.

In contrast to Goda-san, Minegishi-san studied animation in college and has worked in this genre since the mid-1970s. Minegishi-san, has stop motion technology changed a lot since you began 38 years ago?

Minegishi Hiro : Yes, indeed. First of all, the move from film to digital has been a step change. Besides, when I started we didn’t have a monitor to check what we were doing, so we had very little control in the making process. However, now we do everything by computer. For example, we can work on the next frame while checking the previous one, so we can move our models with a high degree of accuracy. In this sense our work has become much easier.

How do you come up with Domo-kun’s story plots? What inspires you?

G. T. : As Domo is a child, he’s constantly daydreaming and everything is new and interesting to him. He reminds me of my childhood, when I used to explore the world around me, constantly living in the present. So every time I create a new story I always think about my childhood memories.

Can you give me an example of one of your memories that you turned into a story?

G. T. : For example, I have an older brother. Once he got sick and my parents, of course, took care of him. I was a little jealous so I pretended to be sick too. I made Domo-kun and Taachan play out the same scene. Domo-kun has become famous worldwide, but I find him very Japanese in character, don’t you think so? What is so Japanese about him?

M. H. : It is true that his gestures are never exaggerated and he seldom overacts. Like many people in Japan, his intentions are often not very clear and remain open to interpretation. This requires the viewer to fill in the blanks, so to speak. It is a very Japanese thing.

Domo-kun was almost born by chance. How about your later productions?

G. T. : That’s pretty much the usual pattern with us (laughs). One of our more successful characters has been Komaneko, which we originally made for a festival organized by the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. It was a chance to introduce our studio on large scale, so we created this female cat that we named Komaneko, because it’s a cat (neko) whose story is told frame (koma) by frame, one frame at a time. Cinema Rise in Shibuya liked it so much that they asked us to make a number of very short segments to show between movie showings. Then more and more people asked for a longer story, and then a sequel and… we just rode that wave.

Do you think Domo and Komaneko attract different audiences?

G. T. : I don’t know about Europe, but in the US, for instance, they treat Domo like a friend and he seems to be popular with all kinds of people. In Japan he is regarded very much as a child. Children treat him like a friend, and adults like a weirdly cute kid. As a character, he is somewhat undeveloped and the only word he speaks is “Domo!”. This leaves a lot of space for audience interpretation, because you have to figure out what he really means. This is one of the things I like most about him. I also like the fact that he has very simple needs. Basically, he just wants to be happy.

Your works have become synonymous with stop motion animation, which is a throwback to an older, somewhat romantic approach to story-making. How does it feel to work like this in the digital age?

M. H. : My mentor and teacher, Kawamoto Kihachiro, was an internationally famous model animation director. He created a whole world with his stories, and I found his vision fascinating. He taught me the fun and joy of expressing my own feeling through the models. The process itself, of creating the illusion of movement through little changes is something I really like.

G. T. : It certainly is a very labour-intensive way to work. Just think that in order to create a one second sequence we need to take 24 photos. We usually work from 10.00 am to 11.00 pm, and in one day we usually manage to produce a five second segment, which means on average we need one week to create a 30-second story. Stop motion animation goes all the way back to the origins of cinema. As Minegishi-san said, there has been an evolution, but it still remains a rather “primitive” style. Both the characters and the background are handmade, and in order to simulate movement we have to move them by hand. So you get that analogue feel. There’s nothing new or cutting edge to it, so it never gets old. In this sense it’s like a children’s book. They never lose their charm even after 10 or 50 years. On the other hand, a film like Transformers looked amazing when it came out, but in a few years will probably look dated. Then there’s the teamwork involved. Now, if you have a computer you can create many different things by yourself, but what we do at dwarf cannot be achieved without collaboration. Working with other people towards a common goal is something I particularly enjoy.

A lot of Domo-kun merchandise is quite different in America and Japan. Are you sometimes surprised by the way your foreign partners manage his image?

G. T. : I’m constantly surprised! (laughs). In Japan, Domo’s image is closely associated with NHK, but in America they can be more free in their approach. They come up with different costumes and other things I would have never thought about.

Your latest important project has been “By Your Side”. What is it about?

G. T. : Soon after the events of the 11th of March 2011, filmmaker Gregory Rood launched Zapuni in order to bring together Japanese visual artists and international recording artists for the creation of films to support children affected by the disaster. I ended up getting involved by working on Sade’s song “By Your Side”. Using the lyrics, “I’ll be there / Hold you tight to me”, as a starting point, I created the animation. I thought a lot about the people who have lost their houses and jobs. That’s something I couldn’t ignore. Hoping that happy everyday life will return to Tohoku may be too much, but I don’t

want to forget any of these things. That’s why I joined this project. I want to support these children who have such immense challenges to overcome.

Interview by J. D.

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat