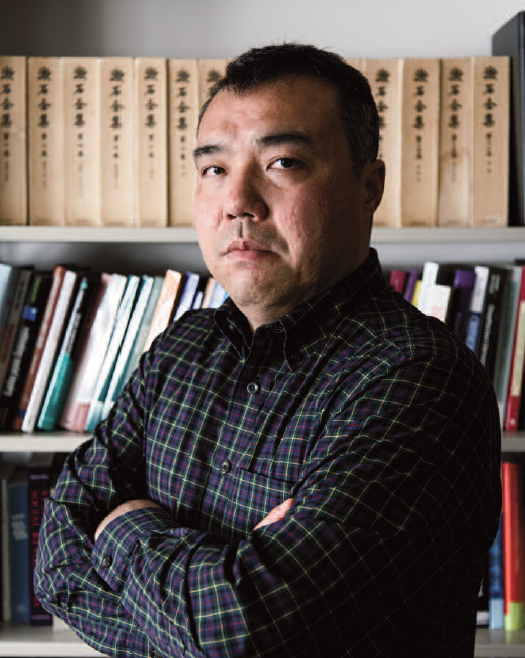

On his recent visit to Paris, the winner of the 2013 Pritzker Architecture Prize returned to the subject of his different projects. Zoom Japon, our French sister publication, made a plea to its readers to help rebuild Rikuzentakata’s community centre.

The donors would like to know what has become of this project.

Ito Toyo: I would like to thank them for their great generosity. In Rikuzentakata it was Mrs. Sugawara, who used to be a hairdresser, who headed the group of people who came forward at the start of the project. She then started a nonprofit organization to manage the centre once it was ready. But truthfully, in view of the continuing lack of housing in the area, and the delay in rebuilding, the centre still isn’t running well enough to welcome people. That is why I started a nonprofit organization called Minna No Ie Network (the Community Centre Network) in order to help manage these places correctly and keep people better informed about their activities. As its president, I submitted this project on March the 11th. It should soon see the daylight, and will help the management of all these centres.

Are the other architects who were part of the community centre project also part of this new organization? I’m thinking of Kuma Jengo, Sejima Kazuyo, Naitoh Hiroshi or Yamamoto Riken.

I. T.: This community centre was Kishin no Kai’s (Association for the Return) project, and it was created by these architects. But currently there’s only Mrs. Sejima working at the community centre. M Yamamoto built a house with the donations that he collected himself. So both Mrs Sejima and I, in collaboration with young architects, have decided to continue with the project. The Kishin no Kai group was dissolved in the spring.

How many houses were built after the one in Rikuzentakata?

I. T.: Currently, there are ten, and a few others are in the process of being built.

How do you select a spot to build a community centre?

I. T.: First of all we visit the cities on foot and then we meet the local authorities (the city hall and prefecture) before drawing up a plan of the building. It’s quite difficult. The project is often well received by the local population, but the authorities usually consider it as potentially extra work. It’s quite complicated as we are in the middle of a period of reconstruction. Moreover, there are big differences between what we think and what the authorities think. But at the end of the day, most of our projects received a warm welcome.

Once they have been built, do you go to look at how people are using the building?

I. T. : Yes, I often go. I visit the first centre built near Sendai and discuss things with the residents over a glass of sake.

Are you asked to build centres adapted to particular locations?

I. T.:Yes, that often happens during conferences. But the residents’ requests alone are not enough to build a community centre. You also need the support of the local authorities. On top of that, the problems we encounter on site and with the project management are considerable.

Is that the same with the construction and the management?

I. T.:Only the construction. As far as management is concerned, the authorities sometimes deal with electricity, gas, etc. There are also cases in which a committee in charge of the social housing takes care of the management. It’s not an easy question to solve. Our new association was created to help with all of that.

How does your association communicate your needs in Japan?

I. T.: We’re more likely to communicate our needs internationally. It is strange but nobody in Japan is used to donating. There were some donations after the earthquake, but three years have gone by and few companies or individuals continue to give.

People don’t necessarily have the same preoccupations today as they had the day after the earthquake. Is the architecture required different according to whether its in a disaster area or not?

I. T.: The first thing that was called for was for community centres to be built alongside the temporary social housing. In the long run, this housing will be demolished as the population starts to build houses outside the city or move into new public housing. Until then, people need somewhere to meet together. And that is the aim of the community centre. I hope to continue building these community centres as long as I can. But now, I believe the time has come for the local authorities to take on this responsibility. We plan on building one in Kamaishi, in Iwate Prefecture. The goal is to create spaces (schools, public housing, individual houses) that operate like the community centres, to demonstrate how we can rethink public spaces. Despite a few very interesting projects, the increase in the cost of construction makes it impossible to build them today. That’s very sad.

Is it always that way?

I. T.: Yes, and not only in Tohoku. The whole country is facing the same situation. Nearly all the architectural projects with agreed budgets still haven’t been started. The cost of construction has increased since the initial budget, multiplying not just by ten or twenty per cent, but by fifty! And sometimes, nobody even replies to the calls for tenders. In my opinion, many workers have been recruited, with offers of a high salary, to build dykes against the tsunami, or to decontaminate radioactivity. This kind of work is easier, so now nobody is interested in more complex building work anymore. And in addition to all of this, there’s a lack of cement.

Do you have ideas to help this situation?

I. T.:That’s up to politicians, it’s their role. From the start, I said I didn’t see the use in creating dykes. But everything was concentrated on the dykes… for political reasons.

Japanese architecture and architects are known all around the world. Last year, you were awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, and this year, it was Ban Shigeru. How do you explain this?

I. T.: Ban Shigeru was very active in disaster areas both in Japan and the Philippines. He was recognised for his perseverance during all this work. But more than just recognising “architectural expression”, the implementation of concrete examples were highlighted. Little by little, the ideas we have about architecture have been changing, and I think that’s good. In the context of the disaster that hit Japan, we need more of these young architects who aren’t just satisfied with what they build in their heads, but who are hands-on as well. That is why I travel with them to disaster areas, in the hope that they will become aware of the problem, despite it not being an easy thing to do.

In the Ito Workshops, you host discussions with very young architects…

I. T.: Yes, I find them very interesting because they aren’t that attracted to being “designer architects”. They are more motivated by wanting to collaborate on small-scale projects and remaining in contact with people. And they are much better at it than I am! That is why I believe architecture is going to change a lot. I really believe that we need to innovate rather than just build something anew.

Is that going to influence your own designs?

I. T.: I prefer local projects to those in large urban areas. In my opinion, since the earthquake, it has been very important to rebuild at the local level. I think I’ve changed a lot because I have been thinking of themes I hadn’t really taken into consideration until now. They imply innovating projects for new cities, in ways I hadn’t imagined until now.

Does this apply at the international level as well?

I. T.: Yes. Metropolises all look alike. In Europe, cities like Paris or Brussels have their own particular characteristics, but Asian cities are all similar. Taipei and Singapore, two cities in which I work, are very dynamic and more receptive to architectural

projects than Tokyo is.

Is there a city in which you might like to build?

I. T.:A city in which there is a human environment. It would be a challenge outside Japan. I have just come back from a month in India. It’s difficult getting around there, but I experienced something very human there, where men, animals and nature live symbiotically. In an ideal environment such as that, I should be capable of constructing buildings that emit a sense of vitality. I went to see Le Corbusier’s buildings, and I believe that kind of environment also left an impression on him. Towards the end of his life, for ten years, he paid regular visits there. He drew a huge drawing on the two-metre wide gate at the entrance of the Chandigarh Palace of Assembly. It represents the sun, the moon, the trees, the water; a constellation of men, cows, birds and other kinds of animals. He describes the impressions he had in India, and it’s beautiful. Without doubt, it is in that kind of environment that an architect should be building.

Interview by Koga Ritsuko

Photo: Célia Bonnin