Politicians are increasingly tempted to play with history. A game that could prove dangerous.

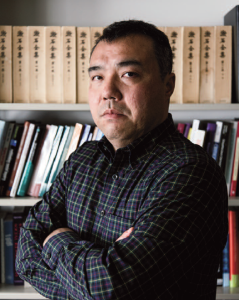

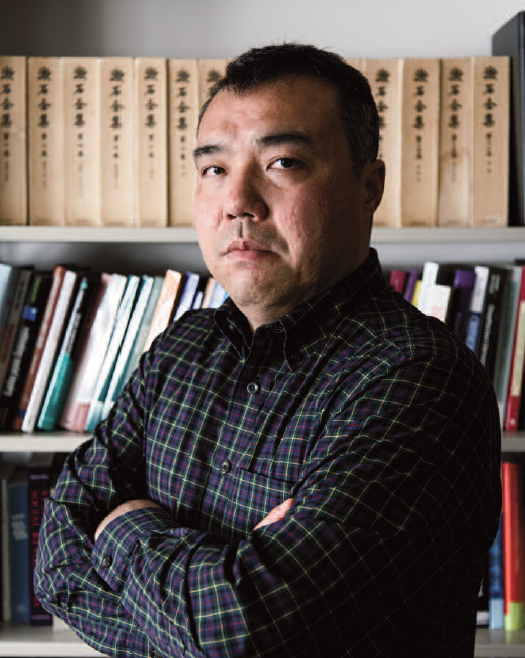

In the ongoing debate on historical memory and revisionism in Japan, it is sometimes hard to tell the truth from ideological propaganda. Therefore, in order to make things clear, Zoom Japan paid a visit to Nakano Koichi, Professor of Political Science at Sophia University and Director of the Institute of Global Concern.

When people discuss Japanese nationalism they often talk about the so-called Yasukuni Doctrine whose name comes from Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. This is not an ordinary shrine, is it?

Nakano Koichi: Yes, indeed. It’s not even part of that brand of state Shintoism that prevailed in the pre-war period. It was built by the Meiji government, and originally it was jointly run by the Army and Navy Ministries, but it’s not a secular memorial either. It’s just a very peculiar military shrine with a very specific view of history.

So what does the Yasukuni Doctrine say exactly?

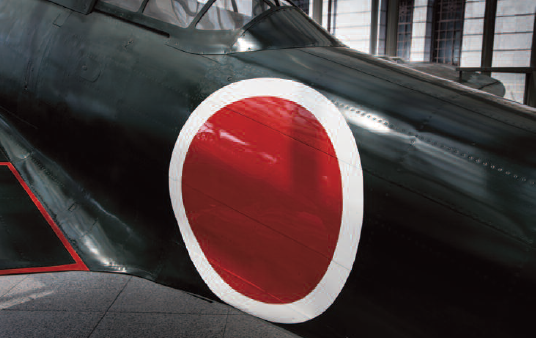

N. K.: It says that all the wars Imperial Japan has fought in modern times were wars of self-defence. Therefore the people who died while fighting for the country’s peace and safety – not only the soldiers, but even the nurses, etc., who were killed in these wars – should be commemorated and treated as deities. Also, the logical conclusion is that those conflicts are never treated as wars of aggression.

What do you think of the visits to Yasukuni Shrine by the Prime Minister and other politicians, from the perspective of the constitutional issue of the separation of religion and the state?

N. K.: As I said, during the pre-war period the shrine was sponsored by the state and was part of the state. During the American occupation it was only able to survive by becoming a religious organization and not part of the state machinery, on the same level as [Buddhist movement] Soka Gakkai or even Aum Shinrikyo were at a certain time. In reality that is not quite the case. Even in the post-war period the Ministry of Health and Welfare continued to supply a list of war dead to the shrine. So the separation is not as clear as it should be. The main problem is the idea of the prime minister visiting Yasukuni in his official capacity. As long as he, or any other politician, does it privately it’s okay, but when it becomes an official duty, then there is a constitutional problem. This incongruity began to be highlighted in the mid-70s. Some politicians played with words in order to make it look okay, but in the end the court system is very clear in stating that using public funds or even public cars to visit the shrine is not allowed. Therefore the constitutional issue is more or less settled. Having said this, there is a good deal of hypocrisy on the part of people like Prime Minister Abe Shinzo (or former Premier Koizumi Junichiro in the early 2000s) insisting on going to Yasukuni just because they head the government. Koizumi was a very good case in point because there is no record to show that he ever visited the shrine before or after he was prime minister. So for him, going in that capacity was very important.

What do you think of this issue from the perspective of responsibility for the war?

N.K.: This, of course, has a lot to do with the enshrinement of 14 Class-A war criminals in 1978, which is something the conservatives had long wanted to do because they consider them to be victims of war, and don’t recognize the 1946 Tokyo Trials verdict. In fact, even though the actual fighting had stopped, the war at that time was not formally over, so they are treated like the soldiers who died on the front lines. Now, Emperor Hirohito clearly understood that the Class-A war criminals were considered responsible for the war. Even Yasukuni’s head priest in the early post-war period shared his opinion, and continued to decline the conservatives’ requests. That’s why the enshrinement occurred only after he died.

Japanese politicians often state that they only want to honour all the people who gave their lives to build a better country. Don’t you think there is a kind of logic in the proposition that the ‘Japan of today’ is only possible thanks to the war dead enshrined at Yasukuni?

N. K.: It’s twisted logic, and frankly, it’s incomprehensible, but somehow it’s a popular argument that keeps being repeated by the conservatives. Actually, it makes perfect sense according to the Yasukuni Doctrine because, as I said, under the doctrine all wars fought by Japan are treated as wars of self-defence. So today we have peace because they fought and died for the country. Never mind that in WWII the Japanese military aggressively pushed ahead as far as Nepal, Indonesia and Hawaii. Of course the conservatives see only what they want to see.

Do you think the government will ever establish an alternative secular memorial to Yasukuni?

N. K.: This debate has been going on for a long time, even before Yasukuni became so controversial. When the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery was built, the shrine resisted and objected very strongly because they knew it would be a rival site. That’s why the memorial is still very small and underfunded. So I think it would be very difficult to do what you asked because, for the conservative factions, that would be an unacceptable way to commemorate the war dead. That’s also why only two months after U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Defence Secretary Chuck Hagel laid flowers at Chidorigafuchi, Abe went to Yasukuni, ignoring the clear message sent by the American leaders.

Many people, both in Japan and abroad, criticize the version of Japanese history presented at the Yushukan (military and war museum). What are your feelings about this place?

N.K.: It’s completely outdated in its worldview. Maybe it carried some weight in the late 1800s when Japan was under threat from the Western colonial powers, just as China was, but it doesn’t explain anything that happened afterwards when Japan itself became a colonizing country.

I’d like to know your thoughts on the government’s efforts to change education and particularly the way history is taught in Japan. I think Mr Abe has already revised the Fundamental Law of education, hasn’t he?

N.K.: Yes, that was Abe’s first Cabinet, in 2006- 7. Well, the Fundamental Law of Education was adopted in the early post-war period during the American occupation, around the same time the new constitution was adopted. It is very idealistic and in complete contrast with the former Imperial Rescript on Education that was issued in 1890. It is all about respecting the humanity of each student. The conservatives have always resented the fact that the Imperial Rescript – which praised piety, sacrifice and all the moral virtues of pre-war Japan – was cast aside and discarded. They particularly resented the emphasis on individualism, arguing it was destroying the moral fibre of the nation and making people selfish. In 2006 Abe amended the law asserting “love of the nation” as the new goal of education.

Speaking of revisionism, while preparing this interview I had a look at Wikipedia’s Japanese- language pages on the Nanking Massacre and the comfort women issue and it seems to me they were written from a revisionist perspective, which of course would be very troubling.

N. K.: Cyberspace in Japan is dominated by the right (i.e. the so-called “net uyoku”), so I believe that the Wikipedia pages are also often sites of propaganda and contested facts. Needless to say, those pages are not written by single authors, so the substance is usually quite mixed, and those on the Nanking Massacre and comfort women contain many references to the revisionist claims – though, at the same time, some key references to reliable mainstream research can also be found.

Interview by J. D.