Japan’s most out-there film maker makes a come back with a feature that recalls his earlier works.

Japan’s most out-there film maker makes a come back with a feature that recalls his earlier works.

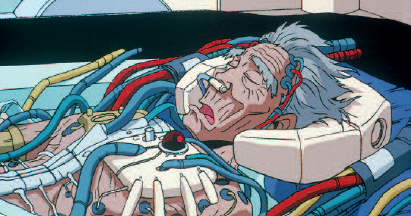

If one hopes for controversial cinema, is Miike Takashi’s new film “Lesson of the Evil” him at his best or at his worst? With a filmography that is as varied in quality as it is prolific, the Japanese film maker seemed to have mellowed over the last few years, directing a series of remakes in a more traditional way (13 Assassins, Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai). This change was so stark that one would be inclined to believe he was trying to gain some sort of recognition from a more mainstream audience. The pace at which Miike makes films was long one of his trademarks, but he has slowed down considerably since 2008, producing a more reasonable 2 films per year. With Lesson of the Evil, however, it’s back to the ferocity of Early Miike, all guns blazing. Lesson of the Evil force-feeds us with nightmarish images, capitalizing in a disturbing manner on the disquieting confusion between pure horror and freaky playfulness. What is does not do is deliver coherent ideas discernible above the prevailing chaos. Miike becomes the victim of his own extreme aesthetics. Yet the film starts in a rather beautiful way, setting up a climate of repressed violence and indifferent cruelty, which reminds us of Nakashima Tetsuya in his excellent Confessions. For a while, we rediscover with pleasure Miike’s work as we know it, cerebral and methodical, as with his earlier film Audition. The opening scene, in this sense, is a great success; the film maker proves that he has some self-control with a scene that still manages to chill us to the bone. But this kind of controlled sadism, truly terrifying, is swept away in the third extravagant act, which borders on obscenity, when the film maker finally loses it by trying too hard to please his audience. After having calmly laid out all his cards then created a lethal tension, Miike brings his film to a climax with a sordid torture scene and at this point decides to up the stakes to follow his morbid inspiration and go over the top. From this point on the violence becomes mere spectacle and truly amoral. Fully aware of the rupture in tone halfway through the movie, Miike decides to film a final massacre in a carnival setting that seems to come out of the blue, craftily creating a sense of detachment. It serves the purpose of intellectually legitimating the outrageousness of what’s about to happen but this single glimpse does not help us forget that this scene seems to last forever without it being really justified. Bringing together such drastically opposed genres, Miike certainly demonstrates his well-known audacity. However, the film stumbles over its own overthe- top performance: overpowering, depraved, decadent and culpable at the level of its own logic of a fatal judgement of error that, in the end, undermines the relevance of its intention. A threatening “to be continued” shown as a final warning tries to support the film makers’ thesis that the violence the audience has witnessed is inexhaustible. But it’s too little, too late. Miike might be aware that he has reduced the intolerable to the level of a simple game, as one of the survivors of the film said almost word for word as she left the cinema. Miike fails to demonstrate the right arguments to justify the perversity of the scenes he has devised. So much so, that it is impossible to tell if we’ve witnessed an abusive but beautiful performance … or just been part of a crude profit making exercise. In this sense, Lesson of the Evil is a most disturbing film for several good reasons; as well as for a vast number of bad ones. The movie is overblown and schizophrenic, gloriously deranged and ends up falling apart at the seams due to its own unsustainable contradictions and accumulated excessess. That’s why, though some may not like it, this film is one of Miike’s most interesting for a while – just not necessarily one of his best.

Odaira Namihei

REFERENCE

LESSON OF EVIL, by MIIKE Takashi. 129 mn. Third

Window Films. T