Every year, at the arrival of spring, cherry blossom casts a spell over the Japanese.

Every year, at the arrival of spring, cherry blossom casts a spell over the Japanese.

Can’t you feel it in the air? The interminable winter is finally over. The days are warming up and getting longer, the birds are singing and the bees are buzzing. This can only mean one thing: sakura season is nearly upon us! And in Japan, wherever there’s a cherry tree, there’s hanami.

Hanami is invariably translated as “flower-viewing”, but this term doesn’t begin to convey the true spirit of hanami. Other languages simply don’t have a word that conjures the image of “getting gently inebriated under a tree and sharing scrumptious food with friends while contemplating the transient beauty of the blossom”. The approach of cherry blossom season triggers a nationwide fervour only seen in the west at royal weddings or cup finals. Each year, as soon as the first tiny buds appear, the whole country is a-buzz with anticipation.

By mid-February shops are already decorated with sakura displays reflecting the festive mood, just as shops in Europe or America put up trees and tinsel at Christmas. Waitresses in traditional restaurants wear pink kimono with sakura patterns.

The feeling of new beginnings is omnipresent. For the arrival of the cherry blossom doesn’t just symbolize the return of life as nature awakens from its winter slumber, it also coincides with the start of a new life for many Japanese people, as a new academic and fiscal year begins, workers take up new posts and students start a new school or go away to university.

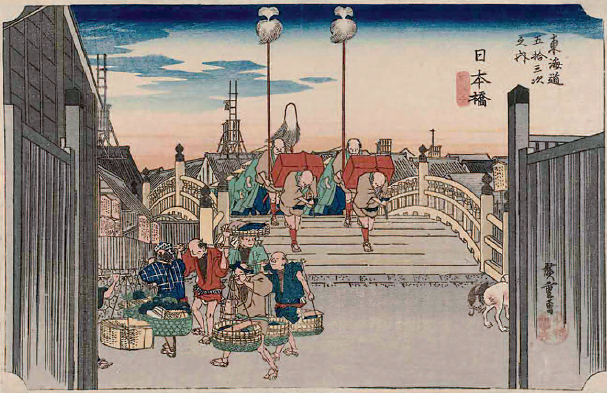

What’s more, hanami spans all differences of age and social position. Young and old, families, friends and co-workers all go for it with equal gusto. Nobody is unmoved or unaffected. The practice of hanami goes back over twelve hundred years to the Nara Period (710-784), although at that time plum trees, which blossom a month earlier than the cherry, were the focus of the celebrations, and hanami only became synonymous with sakura during the Heian Period (794-1185). Back then, hanami parties were only for the aristocracy and court nobility, who were fond of contemplating the blossoms and composing poems. They reached the height of their popularity towards the end of the 16th century and the great warlord and unifier of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), was a fervent fan. His extravagant hanami party at Daigoji Temple in Kyoto (where 1,300 guests enjoyed the 700 cherry trees Hideyoshi had planted) is still commemorated today in the Ho-Taiko Hanami Gyoretsu festival.

During the Edo period (1600-1868), cherry trees were collected from all over Japan and cultivated at the city mansions of feudal lords. As horticultural techniques developed, cherry trees were planted with increasing frequency in public parks, temple gardens and along river banks. This permitted the population at large to start enjoying their own hanami, characterized by abundant eating, drinking and dancing. Nevertheless, there was always a spiritual element to the merry-making. Until the 20th century, Japan was primarily an agricultural country, with over 70% of the population living in scattered village communities. In spring, collective pilgrimages were made to the surrounding mountains to hold parties under the cherry trees and welcome nature’s rebirth. This event brought communities together and was an eagerly awaited part of the pastoral calendar.

After these outings it was customary to bring back a branch of sakura and place it in the rice fields, in the belief that the mountain gods would be attracted down by the beauty of the flowering branch and thus encouraged to protect the harvest.

These divine origins are still manifest today in Japan’s deep-rooted reverence for the blossom. This is why hanami is so much more than just an excuse to let your hair down and enjoy a good picnic. Even now, the communion with nature is a vital aspect. The English poet Keats wrote that “a thing of beauty is a joy forever”, but for the Japanese, the joy derives from the fleeting nature of the blossoms’ beauty.

“We don’t just admire cherry blossoms because they are beautiful, that’s the same for everyone the world over,” says Miyuki Hotta, a 50-year old school teacher. “We also admire them because they fall suddenly, without lingering on. This was believed to be how a good samurai should die too.” she adds. Once the buds start opening, sakura fever grips the nation. So many blossoms to see! So little time! TV, radio and press offer daily updates on the blossoms’ progress, with the blooms’ state of openness expressed as a percentage. Train stations display blossom charts, showing where the trees are at their best. People discuss the stats as avidly as the Brits would discuss the weather.

“They should be 80% open this weekend on Miyajima!”

“They say it’ll be 100% by Wednesday.”

Paper lanterns with light bulbs inside are hung in cherry trees along river banks and in parks, and people reserve their spot under their favourite trees (their “sakura no meisho”) days in advance by simply placing a large blue tarpaulin on the ground with a note bearing the owner’s name. No one would dream of taking someone else’s space once it has been reserved in this way. Once open, the blossoms transform the landscape into an ephemeral wonderland. They brighten riverbanks and public parks, burst out of pine-clad hills like puffs of pink smoke, form luminescent tunnels on mountain roads and soften the harsh edges of the city’s concrete structures. At night, the effect of the lanterns glowing on the pink blossoms creates a surreal candyfloss grotto that becomes quite magical after a glass or two of sake.

Stalls spring up selling festival food, such as squid on a stick, grilled sweetfish, yakisoba noodles and takoyaki (octopus dumplings). Supermarkets set up prominent displays of hanami snacks (edamame, dried squid, senbei rice crackers) and lavish bento boxes containing tempura, prawns, salmon, rice balls, lotus and burdock root, all delicately arranged in separate compartments. Some people prefer to cook up their own feasts, bringing portable hotplates, barbecues and a few cases of beer and the air becomes rich with the sweet-smelling smoke billowing from so many grills. Hanami gatherings begin around lunch-time and can go on till late evening, becoming increasingly boisterous as night falls. The most popular hanami sites can get as crowded as a rock festival.

Some companies even organize their own hanami for all their employees, where you’ll see them sitting cross-legged in their suits and ties, red-faced from all the beer and sake. Some people bring kerosene stoves to keep away the night chill and it is not unusual for revellers to bring portable karaoke machines. After all, who doesn’t enjoy a good sing-song after a few drinks?

Despite the alcohol, the atmosphere remains good-natured, peaceful and almost beatific. The beauty of the blossoms seems to impose an awe inspired respect, as if everybody was in a sacred place. In a way, of course, they are.

And this being Japan, once the party is over, people conscientiously dispose of their rubbish in the containers provided, or take it home with them. The sakura are only at their best for a week to ten days, depending on the weather, so timing is crucial. One heavy rainstorm or one windy day brings them all fluttering down in a blizzard of blossom. All too soon the spell is over, the country loses its pink mantle and reality returns. But it is comforting to remember that when next winter comes around and the cold weather starts to feel like it’s never going to end, little buds will once again start appearing on the cherry trees’ bare branches and hanami season will soon be here to enchant us again.

Steve John Powell

Photo: Angeles Marin Cabello